Why we should re-think who is allowed to be a feminist icon

Olivia Young argues that gender equality will not be achieved by simply placing women in positions of power.

With the appointment of Lord Frost to his cabinet, Boris Johnson has attracted heavy criticism for the low level of female representation in his cabinet. At just 21.7%, Johnson’s Cabinet has one of the worst gender records in recent history. But this poses the question: why should we care? Does the promotion of a woman with whom we probably have little in common have a profound influence on our lives? It is time to admit that it is the implementation of policies to help ordinary women that we should really care about, regardless of the gender of the person who implements them. Men can - and should want to be - feminist icons, too.

There is, of course, the obvious argument that women make up 51% of the population and thus should obviously make up a similarly significant proportion of our elected representatives. That is an argument which no one can look to discredit. Many feminists would argue that having more women in positions of power is a move towards gender equality and helps the feminist cause; Sheryl Sandberg’s self-proclaimed ‘feminist manifesto’ in her book ’Lean in’ sought to offer women advice on how to fulfil their individual ambitions in male-dominated workplaces. It goes without saying that any woman progressing in her career is valuable and should not be criticised. But merely being a woman in a position of power does not automatically qualify someone to be a feminist icon; after all, icons actively champion the feminist cause.

“Women already know this; the problem is that society seemingly does not.”

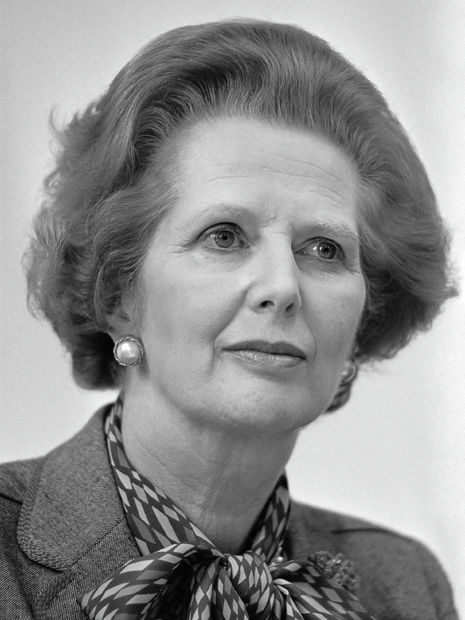

Margaret Thatcher is a case in point. Trickle-down, corporate and 1% Feminism have gained attention in the past few decades, and often hail Margaret Thatcher as an icon for the feminist cause purely because of her gender. Although it is recognised that Thatcher was by no means an advocate for female empowerment or gender equality, 1% Feminists would argue that, by being the first female Prime Minister in the UK, Thatcher encouraged young women to be more ambitious and aim for top jobs. But this rhetoric of a so-called ’ambition gap’ between men and women gives the absurd impression that women inherently have less career ambition than men. Thatcher is supposed to show women that if she can do it, they can do it, too.

But women already know this; the problem is that society seemingly does not. A woman’s personal ambition is completely irrelevant when those in power see this as inappropriate. While women have as much ambition as men, they do not have the equality of opportunity needed to reach it.

Dawn Foster’s ‘Lean Out’ cites studies from the University of Colorado which show that, in the corporate world, women are often reluctant to promote other women since they fear this will worsen their own performance reviews. Female CEOs and managers often feel more vulnerable in their positions and do not want to risk being accused of positive discrimination or special treatment in their hiring and firing powers. Perhaps this explains why Thatcher had no other women in her cabinet and promoted few women throughout her long career.

Another way to think of this is that Thatcher, like many other successful women, identified more with her class than with her gender. The picture many paint of Thatcher as an ordinary grocer’s daughter severely misrepresents her upbringing. Her father may have been a greengrocer by trade, but he was nevertheless a business owner and Thatcher had a degree from Oxford. Perhaps she felt a stronger allegiance to middle-class men, such as Jimmy Saville, whom she advocated for a knighthood.

“Showing women that success is possible without giving them the tools to achieve it themselves is reductive, not inspiring.”

Thatcher once said, “The feminists hate me, for I hate feminism. It is poison.” It is not difficult to see this in her policies: she demonised working mothers and refused to increase child benefits or invest in affordable childcare. How then are these younger generations of women, apparently inspired by Thatcher’s ability to fulfil her political ambitions, meant to fulfil their own? Showing women that success is possible without giving them the tools to achieve it themselves is reductive, not inspiring, and can actively harm women and the feminist cause.

The sooner we realise that there is no inherent tendency for successful women to support other women, the better. This cuts through a strangely active debate in modern feminism: can a man be a feminist? Many feminists would argue not - women are oppressed by men, and men therefore cannot understand women’s struggles. But this misrepresents feminism. This narrative presents a restrictive view of the movement as an issue of man vs. woman, which leaves no room for nuance and our understanding of the many different shades of gender identity.

Barack Obama attracted some criticism for proclaiming himself a ‘feminist’ and saying that all men should be. Of course, Obama’s record for promoting women’s issues during his presidency isn’t perfect: but it’s still far more impressive than Thatcher’s. He may not have been able to effectively protect women’s reproductive rights, but his administration still took some hugely positive steps towards equal pay, combating violence against women and sexual assault on college campuses. The fight for gender equality and feminist movements is a long and complex road, but we certainly won’t get there if feminists disregard the positive impact that can be made by the other 49% of the population.

Simply being a woman is not always enough to be deserving of the title of a feminist icon. Feminist icons must actively champion the cause and look beyond their individual success to consider what they can do to make positive changes for others. With an updated definition of what it means to be a ‘feminist icon’, anyone actively boosting the fight for equality should qualify, whatever their gender. Perhaps, instead of pressuring Johnson to address the gender disparity within his Cabinet, we should be pressuring his government to give a clear plan to tackle the national gender inequality that has been exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic. Will the presence of one more woman sitting around the table at 10 Downing Street go far in helping the thousands of women struggling to put food on the table, or suffering at the hands of domestic abuse? I doubt it.

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026 News / King’s hosts open iftar for Ramadan3 March 2026

News / King’s hosts open iftar for Ramadan3 March 2026 Theatre / Lunatics and leisure centres 4 March 2026

Theatre / Lunatics and leisure centres 4 March 2026 News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026

News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026 News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026

News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026