How schools facilitate innovation – and why we often don’t see it

Drawing on his experience in teaching, Thomas Breakwell argues that creative subjects would not be able to flourish without the sort of teaching often believed to stifle innovation.

Gillian Lynne was a ‘problem child.’ That’s what her school told her mother. Gillian had ants in her pants, she was restless, she was failing school. Her concerned mother took her to the psychologist – if there was a problem, there must be a solution. After observing Gillian in the music room, the psychologist explained that Gillian was an extraordinary dancer. Fast forward in time, and the ‘problem child’ has not failed as an adult. Gillian, now 92, can reflect upon a stellar career as one of the foremost choreographers of her generation.

“The bold, brash, confident creativity of youth is slowly corrupted by the system’s outdated emphasis on drill and kill rote-learning.”

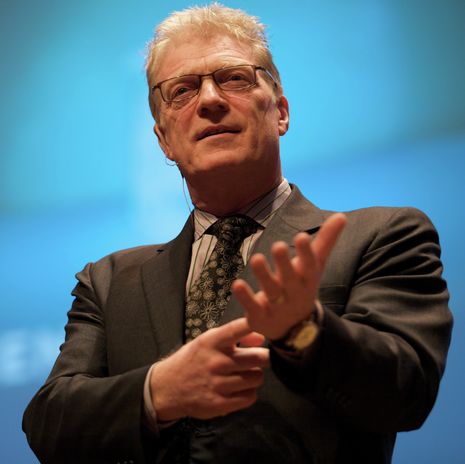

This is just one example given by the late Sir Ken Robinson in his famous TED talk ‘Do schools kill creativity?’ The talk is a YouTube classic. Delivered by an exemplary speaker, it is the most popular TED talk on the site, amassing over 380 million views. Using his classic wit and charm, Robinson lampoons the failures of modern schooling. He describes how schools do not educate young people in creativity – instead, they destroy it. As Robinson provocatively claims, “we don’t grow into creativity, we grow out of it. Or rather, we get educated out of it.”

The bold, brash, confident creativity of youth is slowly corrupted by the system’s outdated emphasis on drill and kill rote-learning of facts irrelevant to the child. In short, if Gillian had not been so lucky, she would forever have been labelled a failure.

The view that schools stifle innovation and creativity is commonplace, from the shadow education secretary Kate Green’s claim that the current curriculum is ‘joyless’ and ‘information heavy’ to Coventry South MP Zarah Sultana’s call for schools to prioritise ‘creativity and critical thinking’. It is easy to see why this view intuitively feels right. Certainly, the English Baccalaureate, introduced by Michael Gove and championed by successive education secretaries, suggests a devaluing of creative subjects. This is further shown by there being fewer Ofsted ‘deep dives’ in creative subjects compared to English and Mathematics.

Schools secretary Nick Gibb’s fondness for traditional teaching methods and a ‘knowledge-rich curriculum’, coupled with Gavin Williamson’s passion for pupils sitting in rows, certainly seems to demonstrate the stifling of creative thinking in English schools. The teacher at the front of the room with 30 pairs of eyes staring back at them is now the norm; I can almost hear Pink Floyd’s ‘Another Brick in the Wall’ starting to play. It is not surprising that modern schooling is often compared to Dickens’ school board superintendent, Thomas Gradgrind.

But sometimes intuition is flawed. Robinson was wrong when he argued that teachers actively educate children out of their creative instincts, because he and his admirers have misunderstood what it means to be creative.

Robinson’s example of Gillian Lynne is a telling one. While he tends to shy away from defining creativity, the example hints at what he deems it to be. For Robinson, creativity is innate, natural – it is to be nurtured rather than nullified by an archaic Victorian school system in which the pursuit of creativity is actively discouraged.

“Children cannot creatively think and solve problems in art, music, dance, drama, literature, and philosophy if they do not have established knowledge.”

The problem is that the vast majority of schools don’t subscribe to this view of creativity. Schools do not stifle innovation – they teach it. Good schools today teach children knowledge which is both relevant to the world around them and outside of their usual spheres of influence, opening up new opportunities to exercise creative skills. What pupils need in order to be creative is knowledge. Picasso and Matisse were only able to transform art because they could paint like the old masters; children cannot creatively think and solve problems in art, music, dance, drama, literature, and philosophy if they do not have established knowledge. Raw talent can only carry us so far.

This is true even in schools that are trying to go against the grain. Let us take the example of School 21 in Newham, London. For some, the school represents a remedy to the sickness inherent in modern education. It is heavily focused on equipping its pupils with 21st century skills, in particular creativity, oracy and learning through group projects and presentations. On the surface, it is Robinson’s dream school.

Yet even at School 21, even at this bastion of creativity, the stifling traditions of education are apparent. Its ‘Head, Heart, Hand’ curriculum is fascinating: it starts with subject specialist teachers teaching pupils ′factual knowledge′ before allowing them to use their hands to be creative and solve problems.

Robinson was popular for many reasons. One of them was that his words, thoughts, and examples – notably, the dazzling talent of Gillian Lynne – resonated with many who had a shared perception of what intuitively feels true: that schools stifle creativity. The truth, in my view, and from my experience as a teacher, is that good schools up and down the country do nothing of the sort. They nurture innovation by giving young people the knowledge they need to be creative – and that is to be celebrated.

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025

News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025 Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026

Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026