We must decolonise study of History at its roots, not just in higher education

Sarah Ibberson argues that we must reconsider what it means to study History as a subject if decolonisation efforts are to reach all levels of teaching

Efforts to decolonise history at the university level are commendable and much needed, but the same vigour has yet to permeate down to secondary education in the UK. Schools need to adopt a new approach that both incorporates a broader range of historical narratives while also developing the way in which history is taught.

The core of the problem is twofold. One, the historical topics covered throughout secondary education rarely provide students with an understanding of the way in which slavery and colonialism have shaped modernity, and the approach taken to historical narratives is not conducive to learning the skills that the study of history should promote.

This second, more nuanced limitation of the current curriculum, stems from the proclivity of history to be perceived as a subject necessitating the regurgitation of ‘facts’, rather than the production of intelligent argument demonstrating sound analysis and evaluation of concepts pertaining to a specific historical topic. Indeed, these central issues inform and perpetuate each other. The lack of emphasis placed on the importance of challenging sources, opinions, and historiography is one of the reasons why the decolonisation movement has only recently begun to gather pace.

The idea that history is written by the victors highlights perfectly the danger that an inability to question historical ‘truths’ poses

By way of an example, students growing up in northern industrial towns are more than accustomed to the history of the surrounding cotton mills and the part the North played in the Industrial Revolution. They are often even informed on the auspicious nature of the relatively humid climate of Greater Manchester for successful cotton manufacture. Yet, rarely are the Cross-Atlantic origins of that cotton production ever discussed, and lessons on slavery focus primarily on the American continent. The evil of the trade in which Britain played a major role, is either mentioned briefly, or discussed in a manner which does not do enough to emphasise the immediate proximity of the UK to the plantations of America, of which the geographical distance is no reflection.

The problem with the narrow nature of the curriculum is then only perpetuated by the way in which history is taught. Unlike other core subjects, history is not about right and wrong answers, it is about questioning and challenging source material. It is as much about interpretation as a chronology of events, and this fact needs to become the core of the subject. Churchill’s infamous assertion that history is written by the victors, highlights perfectly the danger that an inability to question and contest historical ‘truths’ poses. Thanks to the general proliferation of knowledge that has accompanied modernity, we are not so naïve as we once were, but there is still a long way to go and pressure needs to be added to reform the way in which people approach the subject. Teaching the skills of critical source analysis and historical enquiry to challenge preconceived opinions is essential to ensure that the narrow approach to sources isn’t continued as it has been for so long.

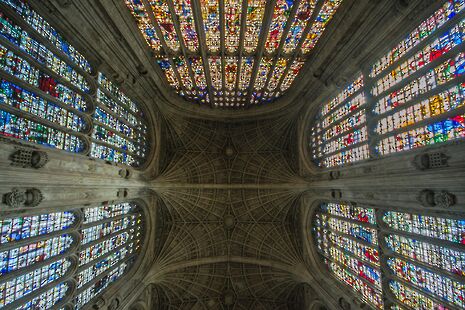

Within the UK there is an excellent framework that might provide a platform for disseminating this message for changing how history is taught. The National Trust, English Heritage, the Historical Association, are to name but few organisations. The sheer amount of time and money that goes into the preservation and education of history is astonishing. We need to push further and transcend beyond seeing only our own nation’s history in our physical landscape. The Georgian architecture of Bath is also a manifestation of Britain’s involvement in slavery and vestiges of colonialism can be found in many an academic institution.

It is time for a more open-minded approach to the teaching of history. The very existence of a rigid curriculum may even be an impediment. The most obvious constraint of this argument is that there simply isn’t enough time to afford all aspects of our past room in a set curriculum. Even then, how do we prioritise? Who is to say that the history of slavery is more or less important than the Holocaust? The beginning of the road may be as simple as affording students the space to research their own chosen topics. Younger pupils should be given more free reign to research and critically evaluate issues that occupy their own interests. There needs to be a transition away from an emphasis on rote learning to critical analysis and evaluation of historical sources and narratives.

The new history curriculum introduced in 2014 placed an emphasis on providing students with an understanding of the general chronology of British history, but with thousands of years of global history to choose from, in a world growing ever smaller, surely, we need to move away from the conviction that historical facts are the be all and end all. While factual knowledge is important it should come together with interpretation. History should be seen as much as a skill as it is a subject, and we need a curriculum and teachers that facilitate this. The only way history will cease to be a malleable tool for any form of agenda is for it to be universally understood for what it really is: contested truths.

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026 News / Cambridge students uncover possible execution pit9 February 2026

News / Cambridge students uncover possible execution pit9 February 2026 News / Man pleads guility to arson at Catz8 February 2026

News / Man pleads guility to arson at Catz8 February 2026 News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026

News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026 News / John’s duped into £10m overspend6 February 2026

News / John’s duped into £10m overspend6 February 2026