The take-home from the closure of a print paper doesn’t have to be gloomy

Nick Harris considers the new direction The Cambridge Student is taking, and how it relates to the national landscape of print journalism

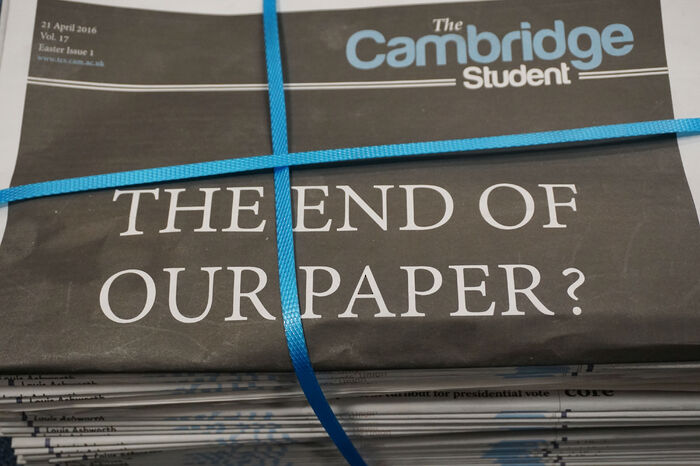

This week it was reported The Cambridge Student would move to an online-only platform. From The Independent over a year ago, to the more recent demise of the printed NME, the ineluctable trend from print to digital continues, unstoppable as a retreating tide. It is only in the memories of whisky-sodden journalistic dotards that the vision of newspapers as the nation’s media nervous system persists, fading into nostalgia as the atrophy accelerates.

The only crumpled remains of a commercial printed tabloid industry are to be found in London, where the Evening Standard and the Metro cling to growth and profitability as freesheets, whilst other tabloids decline. Between 2016 and 2017, the Telegraph reported that its profits had almost halved, and we have all seen the penurious Guardian requesting readers’ donations at the end of every article. The picture is almost unimprovably abysmal, as a two-centuries old tradition of popular printed media seems to end.

But to see this as a decay relies on a particular image of print media, in which it is the unchallenged conveyor of news. With this service now available at no cost online, it would be foolish to expect anyone (let alone students) to part with money for it. It is not an act of theft to only have a perfunctory scroll through the Guardian app, only one of economic rationality. For most consumers, it simply makes no sense to pay for a product when one can acquire it for free.

What is much more interesting is what kind of journalism people, including students, are willing to pay for. The one general area of the print media which is growing at present, in many cases after a long period of decline, is the niche of periodicals. Magazines which supposedly cater for a niche interest, such as the Times Literary Supplement and the London Review of Books, along with Britain’s most august political periodicals, the New Statesman and The Spectator, all report healthy, growing circulations. These expensive publications, sometimes costing upward of £5, rest their reputations on the wit, insight and prestige of their contributors and columnists. They provide something worth paying for, beyond just ‘the news’, an unassailable métier of politico-cultural commentary which retains its market share.

The same holds true for student journalism. Rather than worth paying for, student newspapers have to remain worth reading, providing content which rouses and informs the students they serve. Cultural content which students may find interesting, investigations into injustices around universities, reviews of events happening within a university town – these are things which make student journalism indispensable and therefore desirable.

The take-home from the closure of a print publication does not necessarily have to be gloomy. This is because the trajectory of print across its entire spectrum is not universally downward. As with any marketplace, consumers choose what they are willing to pay for. At a national level, that is no longer breaking news and current affairs, and publications which continued to provide just that will find a print existence eventually unsustainable. In the case of The Cambridge Student, print became the wrong fit for providing immediately relevant content to the student body. Indeed, with TCS Telly it is evident that the newspaper is trying to connect with its audience in a different way. Delivering incisive and enjoyable content can demonstrably keep newspapers worth reading and buying, even if we must consider whether this is the only platform on which journalism can be successfully produced.

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025 News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025

News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025 Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025

Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025 Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025

Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025 Interviews / Meet Juan Michel, Cambridge’s multilingual musician29 December 2025

Interviews / Meet Juan Michel, Cambridge’s multilingual musician29 December 2025