Editorial: I’ve only just admitted this to myself

I’m still trying not to think too hard about the fact that I have an appearance, writes Noella Chye

Content note: This article contains discussion of eating disorders.

I didn’t have a freshers’ week. I remember the morning of my matriculation — so cold and lightheaded I thought I would faint.

I arrived in Cambridge with an eating disorder I’ve had since I was around 10. Up until today I’ve never really told anyone everything. Just two months ago, over the summer, I admitted it to myself.

Lately I’ve thought a lot about when I first arrived. I spent my first term in Cambridge feeling strange and ashamed. I remember looking for people in Cambridge who were writing about it and not finding anyone. When I went home for Christmas, I didn’t want to come back, to return to a place where I’d spend days on end alone, in a rigid daily routine that allowed me to last until the evening without food, saying no to everything – meals, formals, drinks – so I’d never have to deviate from it. I knew then I wasn’t happy, but I didn’t let the weight of what was happening truly sink in. I was so embarrassed about it.

The summer before I came to Cambridge I was forced to see a doctor. He told me I looked frail, and haggard. I couldn’t see it. When he said I had to take a blood test to check if I had deficiencies, I cried. I didn’t want my parents and people around me to have evidence that something was gravely wrong, that they could use to make me change the way I was living.

If I close my eyes and think about the past ten years, I can still picture in my head the details of the most painful moments, and feel the fear, the self-hatred. It doesn’t feel like it’s really happened to me. I can’t believe I’ve been, and still am, in this much denial.

Going into my final year, I realised that someone else will arrive in Cambridge this year dealing with deep-seated insecurities of their own, scared or ashamed of them; who, like me two years ago, hasn’t heard about the insecurities that people face in Cambridge and how it can shape your time here; who doesn’t see it in the people around them; who suspects they may be alone. I felt I had to say something.

I’m writing this editorial because it’s exactly what I would’ve wanted to hear. I’m writing to my fresher self, saying: you’re carrying so much on your shoulders, and I wish I could take it off of you.

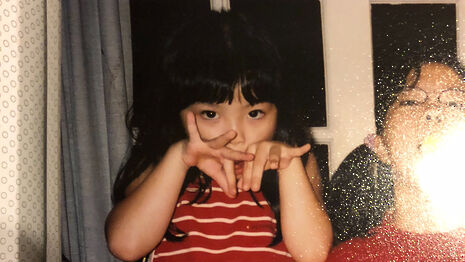

I’m writing this to my nine-year-old self, before it all started, when the first hints of insecurity began creeping up. I have a distinct image in my head of one particular moment at school. I’m with a group of friends just about to climb a blue staircase, looking around at the people around me and thinking about how much prettier, and more normal, and less oddly-shaped they are. I think I remember that moment so clearly because it stands out as one of the first moments I felt I had to do something about that insecurity, that I decided to try to change myself for it. In my mind I’m writing to that girl, in that moment. When I think about her, and how uncomfortable she is with herself and so the world around her too, I feel this immense sadness.

I think fragments of all of these past selves lie in every one of us – insecurity, self-doubt, shame. So I’m writing to you all too.

We have a long way to go in Cambridge in recognising the insecurities we all face – to making this a place where fear is no longer the norm.

This disorder has shaped my life in ways I haven’t fully confronted. I can’t remember what it’s like living without it. I know there’s still so much I’m pushing out of my mind. I still find myself in denial; the only way I can get through each day is by trying not to think too hard about having an appearance. Sometimes I’ll catch my reflection in a glass window and still feel my heart drop. Photos and videos are hard; I can’t really bear to look at them and realise each time that I’m nowhere near liking how I look or feeling like that’s me.

Today Varsity releases a video where four students talk about their experiences with body image. Throughout this week I’ve been thinking about what it would’ve been like watching it two years ago when I first arrived — how I would’ve felt being told that what I was going through wasn’t some sort of wound. That these people have been there. That it’s okay to feel lonely and out of place. That I didn’t have to hide something that was consuming me.

That it’s not my fault for feeling the way I did, that there’s nothing to be ashamed of. That it’s part of the culture here. No more.

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025

Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025