The Irish language has become lost in translation

Nadia Hourihan bemoans how debates over the language’s future in Northern Ireland are dividing Stormont

If you want to translate from Irish, you had better be fluent in Irishness. The Seanfhocal (proverb) writ large on the walls of my Irish classroom read “Tír gan teanga, tír gan anam” (A country without a language, is a country without a soul). Ever since I was very small, I have been aware of a language that has claimed ownership over my country, and me. My home has two names. I have two names: one in English, and one in Irish. Ireland asks its people to operate between languages; we come to know our world in translation.

“Language is constitutive of identity; it is as bold as a flag, and just as divisive”

For anyone who speaks it, passing in and out of Irish is a curious process. The poet Thomas Kinsella argued that flitting between two tongues had engendered a ‘divided mind’ in the Irish, who cannot feel ‘at home’ in the English language. I’m not a fan of his phrasing. It pits a chasm between languages, denying that they can be conversant with one another. I think the truth is that we have ‘doubled minds’ (that is, for the teeny tiny percentage of the population who can actually speak Irish), and we are richer for it. Isn’t bilingualism to be encouraged?

My Granddad gave me the gift of the Irish language. It’s my inheritance. Irish has always been our teanga rúnda (secret language) and it has only ever brought me closer to a man I would happily call my hero. For me, it’s personal.

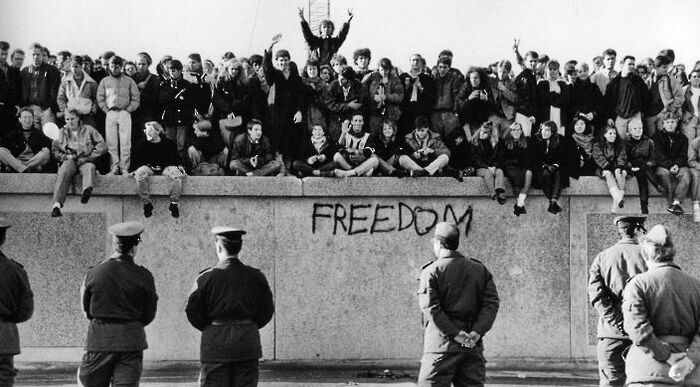

This makes it so very difficult for me to see Stormont being pushed agonizingly apart by an Irish Language Act. It is important to remember that symbols in Northern Ireland are notoriously charged. People have been killed over flags, banners, and whether they went by Séamus or by James. To understand the debates about the Irish language in Northern Ireland, you have to understand the debate about Irishness. Language is constitutive of identity; it is as bold as a flag, and just as divisive.

I love Irish for my granddad. I love Irish for its ornate oddities. Nerdily, I love Irish for the séimhiú (softening) demanded by negation. You’d think that this grammatical toolkit might foster a will to compromise at a time when Northern Ireland’s constitutional settlement appears to be under siege.

It depresses me endlessly to see something so dear to me made a talisman for scorn and sanctimony alike. The DUP is wrong to deny to Irish speakers the same kind of rights already afforded to other indigenous minority language speakers in the UK. Sinn Féin is wrong to choose this as the battlefield they’re willing to die on. Zero-sum politics has Stormont in a stranglehold. We could all do with a little séimhiú

News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025

News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025 Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025

Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025 News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025

News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025 Features / ‘Treated like we’re incompetent’: ents officers on college micromanagement30 December 2025

Features / ‘Treated like we’re incompetent’: ents officers on college micromanagement30 December 2025 Science / Astronomical events to look out for over the break29 December 2025

Science / Astronomical events to look out for over the break29 December 2025