France’s loan of the Bayeux Tapestry should be treated with caution

With the recent announcement of France’s loan of the Bayeux Tapestry to Britain, Guy Birch is wary of those who use it as a chance to forward false historical narratives

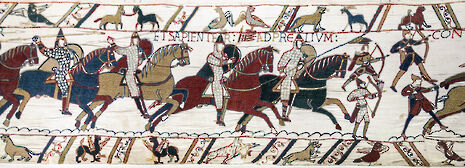

Imagine a power from across the channel interfering with British politics. Imagine a set of uninvited, unelected foreigners with little or no knowledge of Britain’s population, institutions, or culture plotting to overthrow British sovereignty and totally restructure our society. I am talking, of course, not of Brexit, but of William of Normandy’s invasion and victory over the English king, Harold Godwinson, in October of 1066. The story of this conquest is depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry, a piece of embroidered linen over 70 metres long, which for the first time in almost a millennium will be transported from Western France to Britain for exhibition. The craftsmanship of the 11th century embroidery is unparalleled, and it will obviously be fantastic to add such a masterpiece to the British Museum in London, currently the favoured location for the tapestry when it arrives in 2022.

The loan of the Bayeux embroidery, however, has given many in the media an opportunity to comment on history and contemporary politics. While I welcome that the artefact has sparked a national dialogue, articles such as those by Jonathan Jones and Martin Kettle in The Guardian, which attribute the loan to the savvy politics of French President Emmanuel Macron, are deeply flawed in their own way.

“The embroidery is not one we should use to explain our lives now, nor mock those who vote differently from ourselves. It is something to view critically, as with all historical sources and artefacts. History cannot and should not be used to score political points”

What these articles underline is the irony that riddles our national historical narratives. Such narratives are everywhere. Not only in newspapers, but also on television and online. Some of these are relatively harmless, such as the history of medicine, which is seen as a simple history of incremental progress. Some, however, are less benign. For example, I, and I’m sure many others, were taught that a key factor in Hitler’s rise to the chancellorship in 1933 was Germany’s proportional representation system. This is wrong, and it is dangerous. History is not something which can be taught to prop up our institutions and their inner workings. The history we are taught at school, college, and university affects the present we create. If we only learn what fits in to an existing institutional framework, then we fail to properly question and challenge the politics and structures of our own society.

With regards to 1066, the traditional narrative is that with the Normans came the birth of English kingship, uniting the once disorganised kingdoms which made up Britain. More importantly, however, 1066 is when the vast majority of schools teach that our national history began, ignoring the more regional centuries before it. By comparing the events depicted on the Bayeux Tapestry with the perceived foolishness of today’s Brexiteers, Jones makes the point that using any single event to explain an identity, feeling, or mood is ridiculous. The same could be said about many historical events. Why are the Brexiteers not outraged by the kingship of the German George I, the Glorious Revolution’s Dutch connection, or the Roman invasions of the 1st century AD? Isn’t it funny that the Jacob Rees-Moggs and Nigel Farages of the world find modern interference from Brussels to be an attack on our sovereignty yet venerate the past as though it involved no foreign interaction whatsoever?

Jones is obviously right that we can’t cherry-pick facts to back up our arguments, but in a way he is guilty of doing the same from the other side. The Bayeux Tapestry does not tell a story of how interconnected Europeans are. Indeed, it does not comment upon the revolts of the English aristocracy against the French kings over decades and centuries, nor the fact that after the defeat of Harold, the leading barons and clergy proclaimed another English king, Edgar, whose defeat in London finally allowed for William of Normandy’s coronation on Christmas Day, 1066. This resistance to Norman, and later Angevin and Plantagenet rule would rumble on for centuries. It instead tells a story that was supposed to be remembered, one of reneged promises and military might. The embroidery is not one we should use to explain our lives now, nor mock those who vote differently from ourselves. It is something to view critically, as with all historical sources and artefacts. History cannot and should not be used to score political points.

In 1066, as with Brexit now, there was contention and debate, hatred and anger. I look forward to seeing the tapestry in the UK – it is a work of beauty and of great national interest. I also hope, however, that we will see an end to the misuse of artefacts in falsifying historical narratives and begin to enjoy the fact that our present is just as messy, complicated, and diverse as our past.

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025

News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025