The rise of the unelectables

In light of the French presidential elections, Chloe Merrell wonders how voters can truly express their dissatisfaction

Part of my interest in the French election is an inherited one; my mother is French, and so she returned back to France to perform her democratic duty by voting in the crucial presidential election. When I asked her which candidate she would be voting for in the second round she defensively replied: “Well, I’m not voting for Macron.” Mildly horrified, I promptly reminded her of the obvious, that the only other option was Ms Le Pen, to which she paused and slowly said: “Now I know how the Americans felt.” My mother’s reaction took me by surprise. Albeit unknowingly, in that one moment she had accurately captured the current state of affairs in today’s global politics. We are experiencing the rise of the unelectables.

Some might refer to the idiom of being stuck between a rock and a hard place, others might use the phrase ‘the lesser of two evils’. Regardless of the image we evoke to best capture this situation, when the French arrived at the polling booth there was a crisis of choice.

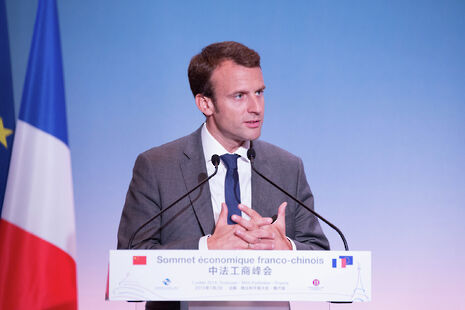

Millions of us watched the French election results closely and with a cautious eye. Would France join the global rising tide of nation-centred populism that had engulfed the UK and the USA with the Brexit result and Donald Trump? Or would she steer clear of this course, opting for calmer waters? On the 7th May our proposed questions were answered. France voted in the independent centrist Emmanuel Macron, defeating his rival Marine Le Pen by 66.06% to 33.94%.

Western leaders and figureheads promptly joined European Union Council President Donald Tusk in congratulating the French for choosing “liberty, equality and fraternity” and for saying “no to the tyranny of fake news.”

However, whilst it may be easy to herald this victory as proof that the continent was not about to sell its soul for the delights of anti-immigration, nationalistic rhetoric, there is one statistic that has gone largely unheard and unnoticed, one that reveals that there is another problematic trend in global politics.

For the 2017 presidential election France had 47.5 million registered voters. Yet, when it came down to vote in the second round, 25 per cent abstained from casting their ballot – people who had previously voted in the first round. If we include the further 8.6 per cent of individuals who spoiled their ballot or left it blank, the total number of people who abstained was 12.1 million. To put this statistic in its proper context, Ms Le Pen gained a record breaking 10.6 million for the Front National and Mr Macron earned over 20.8 million. Let us not make the error of underplaying the significance of this abstention statistic. To put it crudely, Ms Le Pen in fact came third.

“Looking forward to elections to come, the phenomenon of unelectable leadership is still prevalent, and will continue to exist if we don’t somehow find a way of expressing our dissatisfaction.”

We are constantly commanded to vote, told that it is our democratic obligation to exercise our voting right, to choose the person that best represents us and our sentiments. This is what my own mother kept harking back to when she decided to vote and not spoil her ballot. Yet what are we to do when we simply can’t choose? What if both, or all candidates, are simply inadequate? Do you pick the oxymoronic, mainstream antiestablishment figure, or the candidate who has never held office? What if suddenly we were dragged backwards to Michigan on the 8th November 2016 and were faced with decision between Trump and Clinton? So do we vote for “Putin’s puppet” or the “Nasty Woman”?

Prompted by the conversation I had had with my mum, I reached out to a family friend who felt wholly appalled by the choice he had to make, so much so he became part of the 25% who did not vote in the second round. Given the weight of expectation on the French for the choice they were to make, when I asked him if he felt guilty for not doing his duty by voting, he decided no, he didn’t. Instead, he felt that he belonged to a “new movement” who demonstrated by their dissatisfaction by abstention. They had “refused to affiliate” themselves with a “corrupt system”. Abstaining was their way of “rebelling” against a system that no longer held their best interests: frustration, it seems, clearly reigns. Macron, for him, was not the face of a new and improved brand of politics, but rather, he was the candidate the establishment had secretly forged to ensure they did not entirely lose their political hold. However, the thing that I found most remarkable about his answers was the tone of pride in his voice when he spoke of the ‘we’ who had abstained. There had been no conferring and no planning in advance, and yet somehow they all took the same course of action, marking the dissatisfaction in the same way in order to make themselves heard. But is there anything that can be done to address the fact that current politics is being frustrated by a lack of credible and accessible candidates?

Perhaps it is time that we called upon our friend R.O.N, to have a re-open nomination option on our ballots, or perhaps the even more damning, simple ‘no-vote’. Maybe then this discontentment that is so ripe and so obviously felt amongst the French electorate could actually be translated into a mandate, a mandate that would shake up politics – ‘you’re not good enough, please try again later.’ The structure of France’s election with the two-round system shows people are bothered: they felt compelled to vote in the first round and yet not the second. It is not therefore laziness of idleness that stopped this 25% from voting; it was a distinct lack of choice. This, however, is the greatest risk that comes with choosing to abstain. What is supposed to be an act of defiance can become conflated with laziness or indifference. Perhaps this in unsurprising. We do after all see examples of this political apathy all the time in Cambridge across the voting spectrum. First it is your college OGM that you can’t be bothered to attend, then it is the uninteresting CUSU elections. The question now on everyone’s lips, is will this apathy prevail during the upcoming general election?

The suggestion of a ‘no-vote’, is only a suggestion and not a proposed solution. Looking forward to elections to come, the phenomenon of unelectable leadership is still prevalent, and will continue to exist if we don’t somehow find a way of expressing our dissatisfaction. For now, let us at least recall the one thing we certainly can learn from this exercise: while on the surface this election looked like the result we had all been hoping for, there continues to be something darker and murkier underneath, quietly brewing away

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025

News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025