Latest figures show gross disparity in college endowments

Trinity towers above other colleges with net assets of more than £1 billion

The latest release of college accounts reveals a more than tenfold difference in the financial resources per student between the wealthiest and least wealthy colleges.

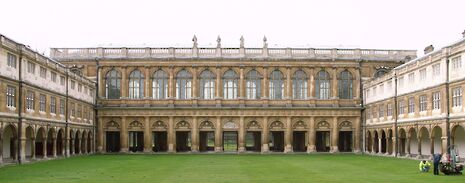

Trinity College, with net assets of more than £1 billion, has resources on a vastly different scale than St Edmund’s, with assets of about £13 million.

Amid concern over inequality between colleges, the 2014-15 reports highlight that the disparity in the size of financial resources continues to grow.

Trinity — historically the wealthiest college — is followed by St John’s, with assets of £690 million. The other colleges each have assets less than one-third that amount: Jesus, with £295 million, and Peterhouse, with £284 million, are next in the rankings.

In terms of assets per capita, Trinity — with more than £1 million per student — is a far cry from Queens’, with only £90,000 per student. Fitzwilliam and Homerton are also near the bottom of the list, with £95,000 and £120,000 per student, respectively.

“I think that students at Homerton are keenly aware of the differences between colleges in terms of money and funding,” said Ruth Taylor, the Homerton JCR President. “I also think the issue is one of perceptions as much as resources themselves.”

The graduate-only, mature and women’s colleges fall even further below. St. Edmund’s has only £33,000 per student, and Lucy Cavendish, £67,000.

The difference between the wealthiest and least wealthy colleges, Trinity and St. Edmund’s, grew by £62 million from 2013-14 to 2014-15.

But endowment and net assets might not have a direct impact on student life in the way that the college’s expenditures do. In this regard, the colleges still display some degree of inequality — Trinity spent £67 million compared to Murray Edwards’ £7.7 million — but most colleges spent about £10 million in 2014-15.

Funding is partially equalised by contributions to the university’s Colleges Fund, which differ in size according to the financial position of each college.

Last year, Trinity’s contribution totaled £2.2 million, while Peterhouse’s was £241,000 and Sidney Sussex’s was only £33,000.

Grants can be made from the fund to colleges to support individual or recurrent projects.

But some, including Paul ffolkes Davis, Trinity Hall’s bursar, have argued that the program “needs review”.

“The system is creaking, and the time when the Colleges’ Fund which supports the younger, poorer colleges will need to be overhauled is fast approaching,” he wrote in the college’s report.

Other programs to equalise funding across colleges exist, primarily the Isaac Newton Trust, which supports fellowship schemes for less well-endowed colleges to hire young teachers and researchers.

Trinity College, which founded the Isaac Newton Trust and contributed £1.5 million last year, claims that 20 per cent of its budget provides for student support and teaching across the university.

“[Trinity] College’s relatively healthy financial position must therefore be seen in the perspective of the College’s many responsibilities,” according to its website.

Its total donations dropped, however, from £5 million in 2013-14 to £4.3 million last year.

College endowments depend in part on their history. The size of Trinity College’s assets is in part explained by “astute investment decisions” that have built upon Henry VIII’s original endowment in 1546, said Fiona Holland, the communications officer for the college.

In terms of absolute size, Cambridge is the wealthiest university in Britain with an endowment of £5.9 billion, compared to Oxford’s £4.2 billion. Still, both pale in comparison to the assets of private universities in the United States. Harvard, for example, has an endowment of about $37.6 billion.

News / Cambridge bus strikes continue into new year16 January 2026

News / Cambridge bus strikes continue into new year16 January 2026 News / Uni members slam ‘totalitarian’ recommendation to stop vet course 15 January 2026

News / Uni members slam ‘totalitarian’ recommendation to stop vet course 15 January 2026 Science / Why smart students keep failing to quit smoking15 January 2026

Science / Why smart students keep failing to quit smoking15 January 2026 Interviews / The Cambridge Cupid: what’s the secret to a great date?14 January 2026

Interviews / The Cambridge Cupid: what’s the secret to a great date?14 January 2026 News / Cambridge local elections to go ahead in May despite local government reorganisation16 January 2026

News / Cambridge local elections to go ahead in May despite local government reorganisation16 January 2026