Strange Bedfellows

Male students and academics are heading to Grindr to find casual sex together. Is technology changing power dynamics within the university?

Ben* waited for Simon’s reply to come.

A first-year English student, he was outside the Buttery at the Sidgwick Site on a hot day in exam term. Simon was not the first man he had met via an app – he describes himself as a “massive fan” of them. He is quite open about using them frequently, and about the encounters he has as a result. “I don’t pass round names,” he says. But this meet-up was different.

“We were chatting,” he says. “Standard flirty chat. I don’t remember who made the offer to do what first, but we went to his room near the Sidgwick Site.”

Simon, who described himself on Grindr as a “member of the university”, was in fact a Senior Lecturer, Director of Studies, supervisor and a fellow of a central college. The room in question was his college-owned accommodation, something Ben describes as “reckless”.

“I left cordially, on good terms,” he says. “We chatted again a few times on the app afterwards… but it was an off-the-cuff suggestion that happened the same day.

“I never saw him again in real life.”

Ben’s experience is not uncommon. Grindr, a geosocial networking application that shows a list of profiles of men near you, has revolutionised how gay men meet – for hook-ups or otherwise. It has become a staple in the global gay community, available in nearly 200 countries, with millions of users. A cursory glance illustrates its popularity in Cambridge: at most hours of the day hundreds of men are online, and its users are highly active. Many are associated with the university – students, researchers and lecturers can all be found on the service, and the level of anonymity it affords makes it easy for people to meet almost any type of man they want.

“One of my theories is that Cambridge people on here don’t really have time for real socialising, and end up using Grindr more than people in other places because of how insane Cambridge is,” one student user told me.

“It’s always been a fantasy of mine”

For Seb, this widespread popularity made certain things much easier.

“It’s always been a fantasy of mine, to have sex with a supervisor,” he admits. He consciously sought out supervisors and fellows, revealing that he was “turned on” by the attention from older, powerful men.

Seb graduated last year, and was a frequent user of the app and similar services before leaving. In total, he estimates he slept with four supervisors he met via apps – and they weren’t hard to find. Academics who state their occupations are easily found on the service. One describes himself as “proudly indiscreet”. Others even specify their areas of research.

Seb admits that he might have slept with more, however – some never told him what they did. As Ben tells me about both of his meet-ups with fellows, he wasn’t aware of their exact occupation until “a decent way through the conversation”.

Initial discretion, however, does not equate with hiding: Ben believes that neither of the fellows he slept with were actively trying to conceal their occupation. “It didn’t really come up,” he states. It is simply a matter of choice: some fellows flaunt their status; others prefer to be discreet.

Some students feel a strong attraction to figures of authority.

As one geography fresher put it: “The idea is kind of hot: to be the object of desire of an older, very intelligent man is flattering, and I think a lot of young guys will be drawn to the whole experience and power dynamic.”

It doesn’t matter for Ben whether or not the older man is a fellow – it is more the case that, in a small university city, many older men in the centre of town have a connection with the institution. But while not specifically attracted to the power dynamic, Ben admits that the idea of sleeping with a supervisor was a turn-on.

“It was collaterally exciting, especially doing stuff like going to fellows’ rooms… it’s the context of a college, especially the older colleges, that makes it feel quite clandestine.”

Everyone I spoke to drew the line at their own supervisor, however. As Seb put it: “It crosses boundaries.”

“I think a supervisor should never sleep with a supervisee, and if he does, then he should declare it to the college and recuse himself, for that person,” he argues.

Grindr allows you to unilaterally ‘block’ users at any time, preventing you from seeing and getting into contact with each other on the app.

Seb saw one of his own supervisors on the service, and blocked him “because it would have been too awkward”. Supervisors frequently admit to doing the same: one PhD student I spoke to who supervised Part 1A chemists blocked one of his students when he saw him.

For James, an undergraduate at a central college, one fellow, Bill, stood out in particular.

“He’s sent me messages before, even pics, but then blocked me when he found out I went to his college. But then a couple of months later, he does it again.”

The second conversation was much the same as the first. No pleasantries were exchanged: the supervisor opened by saying “hot”, which disappointed James, who was mindful of when Bill did this the first time. He decided to continue the conversation, to see if Bill would cross Seb’s boundary.

“I just said ‘thanks’,” James says. “He asked what I was looking for. I said: ‘Nothing in particular,’ and asked what he was. He said something along the lines of ‘Hot fun with hot guys’, that he was ‘very oral’ and that I could turn up to his room, have my cock sucked, and leave.”

This time, Bill sent a photo of his nude reflection in a mirror. James showed it to a friend.

“Oh my God,” she cried. “That’s where I had my interview!”

After sending more pictures, Bill also sent a location, a room in a building James already knew.

“At this point I told him I was at his college, and he blocked me.”

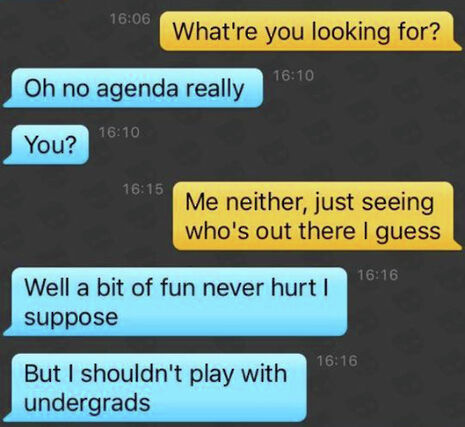

He also spoke on the app to another fellow and lecturer in Languages who, after a brief, flirtatious conversation, told him: “I shouldn’t play with undergrads.”

Student users readily acknowledge the potential for risks and abuse, including the fact that abuse means students are far less likely to speak freely about their experiences.

“I don’t think the university has a problem, because a problem is when the dynamic is abused, and in those cases people are a lot less likely to come forward anyway,” Ben argues.

“You’re much less likely when you’re quite drunk to have a giggle with your best friend about sleeping with a fellow if it was in a compromising situation that you didn’t enjoy or didn’t feel like you consented to.”

But Ben believes apps actually help to clarify difficult issues like consent.

“If I respond to a message, then it’s from the same position as if I’d sent the first message, so there’s no real tangible difference,” he believes. As one maths supervisor put it to me: “Nothing wrong with other undergrads on apps, if they are consenting adults.”

Chris, a PhD student and supervisor, agrees, and sees no problem with sleeping with an undergraduate in his faculty.

“It depends on how mature the person is, and you can very easily gauge how mature people are,” he says.

The new normal?

What about that other gay Cambridge institution: the candlelit Adonian Society dinner at Peterhouse? Many cited it as a turn-off.

“Grindr provides a nice buffer to going up to someone at high table and asking for their number, which obviously you wouldn’t do,” Ben says. “You don’t need to wait for an invite.”

He argues that apps have changed the dynamic, facilitating meetings between supervisors and students without troubling a teacher-student dynamic – unlike the dinner.

He received an invite from someone he met at the university who offered to “sponsor” him, paying his £70 ticket.

“The reason I turned the invite down was because there was then that dynamic… Him offering to pay makes that dynamic so much worse.”

Seb also expressed reservations. “It’s not so much that I actually wanted to go – I know a friend who went and he found it weird. At one point they blew all the candles out, and then people were outside, in the deer park, having sex in the bushes.”

Chris, who has been going to the dinners since his MPhil four years ago, is sceptical.

“It’s never been a hook-up thing,” he says. “I find it quite funny that people always have this idea of this sleaze of academic power dynamics.

“The people getting off in the bushes, it’s always undergrads with undergrads,” he claims.

Is Grindr having an impact on the society? “I don’t think there’s any crossover. Grindr is not a virtual version of a five-course dinner in Peterhouse.”

For Chris, the distinction between casual sex facilitated by an app and a dinner is crucial.

“If you just talk to someone on Grindr, go round to their house and have a shag, yeah, you’ve met them, but if you sit next to someone at dinner and have a conversation with them, that’s a completely different context.

“If you’re saying, ‘Has Grindr changed the ability for students and supervisors to meet to have sex?’ of course it has, it’s a lot easier. But it wouldn’t be fair to not distinguish between those two types of meeting.”

Undergrads put off by the society’s reputational baggage, however, appear not to be likely converts. Grindr is here to stay.

“It seems a much more egalitarian approach,” Ben believes. “There’s a lot more agency with the student. It felt much more like something that happened between equals.”

It’s not just used for hook-ups, either. Seb tells me that he dated a supervisor “for a bit – not in my subject – but he got too intense. He’s now in Chicago.”

Perhaps paradoxically, the net effect of the explosion in app culture is to reinforce the separation between public and private. Students and their superiors have been hooking up for far longer than the university has acknowledged. By making encounters easier and providing an outlet for those who do find attraction in age and experience imbalances, without forcing them to resort to clandestine dinners or their own supervisors, the student-teacher relationship is reinforced.

*All names have been changed.

Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026

Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026 Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026

Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026 News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026 News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026

News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026 Fashion / The evolution of the academic gown24 February 2026

Fashion / The evolution of the academic gown24 February 2026