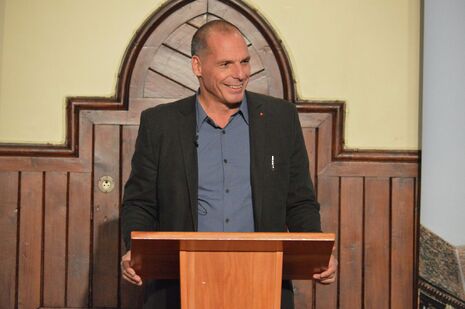

Varoufakis: “Europe is a cartel”

The former Greek finance minister, branded a “traitor” by his own party, said that the single currency has “failed spectacularly”

Yanis Varoufakis is a man who has been both within and without electoral politics. An academic economist specialising in game theory, his career took him from Athens and Sydney to Texas and, yes, to Cambridge in 1988.

In January 2015, however, he was thrust into the spotlight when he was made Finance Minister in Alexis Tsipras’s Syriza government, a far-left administration that swept to power harnessing popular discontent, armed with a mandate to “end austerity”.

After voting against the European bailout terms supported by his own government in August, he was ‘kicked out’ of Syriza along with other MPs, dubbed “traitors”. Unlike many of these MPs, he did not however join the new Popular Unity party.

In an event jointly hosted by the Cambridge Union and the Marshall Society on Monday, he defended his actions in government. Despite his reputation as an intractable negotiator, he claimed that he wears the ire of Greece’s creditors “with pride”.

He claimed that he has “no regrets” about his seven-month stint in Greece’s Ministry of Finance which saw him forced to resign after his opinion differed from that of the Greek people over whether Greece could sustain withdrawal from the euro.

The talk, which lay somewhere between a speech and a lecture on history, politics, economics and international relations, gave Varoufakis an opportunity to lavish praise on Cambridge’s Keynesian school of economics, which, for him, is in short supply in the corridors of Brussels.

Unsurprisingly for a self-described “erratic Marxist”, the theme of historical inevitability suffused his presentation, drawing heavily on the contemporary relevance of Keynes’ work.

His analogies between Keynes’s warning against the post-World War I gold standard and his own protestations about the pitfalls of European Monetary Union (EMU) made clear that he, like Keynes, was a lone voice of sanity in a wilderness dominated by the desolate austerity offered by neoclassical economics.

Varoufakis’s critique of the European project has two main threads. The first was the economic illiteracy of the single currency, which he contended had “failed spectacularly”.

In prophetic fashion, he intoned that “history of economics … is going to report that EMU was designed to fail” and his presentation focused at length on the follies of a single currency without the requisite “investment pillar” to balance weaker areas.

His second line of attack was his contention that the creation of the European Union was not the triumph of the free-market nirvana of popular parody. Instead, Varoufakis argued “we are experiencing … the failure of a cartelised Europe that is also democracy-free” and has “no recourse to the popular will”.

Despite his unremitting attack on the failure of the European project, Varoufakis argued that, for Britain, his experience was “not a reason to get out of it”. Interestingly, he thought that the organisation which had instituted a bailout plan intended to “crush” Greece was actually capable of democratic reform.

While he held out little hope for the success of David Cameron’s negotiations on the terms of Britain’s membership of the EU, Varoufakis placed some faith in the powers of a “pan-European movement” that could act as a driver of change, placing pressure on the continent’s supranational institutions.

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026

News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026 News / New movement ‘Cambridge is Chopped’ launched to fight against hate crime7 January 2026

News / New movement ‘Cambridge is Chopped’ launched to fight against hate crime7 January 2026 News / Uni-linked firms rank among Cambridgeshire’s largest7 January 2026

News / Uni-linked firms rank among Cambridgeshire’s largest7 January 2026 News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025

News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025