Alex Wickham: Why I exposed Brooks Newmark

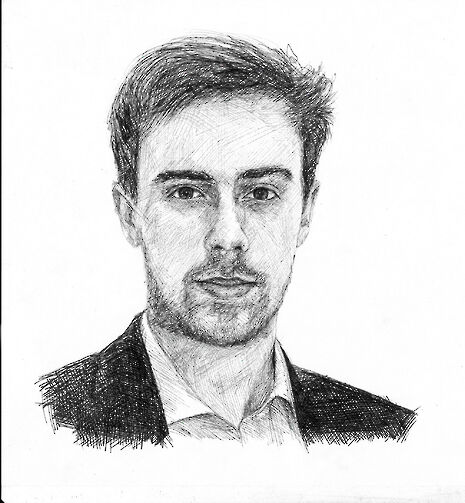

In his first interview since the event, Alex Wickham tells Elissa Foord about exposing the sex scandal that rocked the Tory conference

“It’s been crazy.’’ In the past few weeks, Alex Wickham has exposed a parliamentary sex scandal, prompted the resignation of a government minister, ramped up the pressure on David Cameron over women in politics, and found his sting under investigation by the Independent Press Standards Organisation (IPSO). ‘‘Crazy’’ might just cover it.

When Brooks Newmark, the now former Minister for Civil Society, sent a series of flirtatious messages and lewd images over various social media (including of himself clad in paisley pyjamas exposing his genitalia), his intended recipient was a Tory PR called Sophie Wittams. She was young, blonde, attractive and, unfortunately for Newmark, an invention.

The man with whom he was in fact corresponding was Alex Wickham, who created the character of Wittams..

As Newmark co-founded Women2Win, the campaign leading the drive to get more Conservative women into parliament, such exploitation of power is more than a little embarrassing for the Tories, and more than a little worrying for anyone who cares about gender equality in politics. But its revelation has also prompted an outcry from a different quarter: media standards. The words ‘entrapment’ and ‘fishing’ have been bandied about. The machinery of the new media regulatory body, IPSO, has swung into action, calling Wickham’s investigation a “matter of urgent public concern.”

‘‘Frustratingly, a lot of what has been written by journalists who’ve never broken a story in their lives, mainly at the Guardian, has been very uninformed,” Wickham laments. “They seem to think we just randomly tried to do in a load of Tory MPs, which is far from the truth. We had a very specific, explicit tip-off.’’

The almost 100 other MPs that Sophie Wittams’ Twitter account followed, then, were a cover story and not targets? ‘‘Mr Newmark was the priority for the investigation,’’ he states firmly. The revelation of a second series of ‘sexts’ sent by Newmark, this time to a real woman, seems to have vindicated Wickham, at least in this regard.

Given that IPSO is so newly established, this case will be a landmark. It seems likely that IPSO will want to take a stand and give the press a taste of the discipline of this new, regulatory era. This is a chance for it to flex its muscles. But it must tread the ever-perilous line between regulation and censorship: “This is an important journalistic enquiry into the man who was in charge of getting women into the Conservative Party, and abusing this position,” Wickham insists.

His argument for public interest is compelling. It is hard to view the alleged conduct of Newmark, who initiated the conversation with ‘Sophie’ himself and directly requested that she send him sexually explicit photographs, as anything but a gross abuse of his position. Wickham tells me that he’s received a lot of comments since the story broke from women who work in parliament ‘‘who’ve basically been saying, ‘thank you, well done,’ and that this is something that needed to happen.’’ He adds that ‘‘it’s not journalists who are the people that should be treated with suspicion; it’s the people with real power. It’s the politicians, it’s the ministers, it’s the people who are in charge of candidate selection processes for political parties, it’s the people who women, if they want to go into politics, have to go through, who abuse their position.’’

This case is faintly reminiscent of another sex scandal involving men in positions of power, abusing that power through involvement with the people to whom their positions granted them access. A case in which those affected could not speak out, and in which media standards were called into question, but for quite different reasons. The details differ greatly, and no question has here been raised of non-consentual, or paedophilic, relations. But I wonder how much the public interest would have been served, and how much damage to victims who could not protest themselves could have been averted, by an operation of similar methods directed at the now shamed BBC employees of the 1970s and 1980s.

But the critical question is, do valid ends justify any means? Not according to past media regulation. IPSO’s policy is that subterfuge must be used only as a last resort. ‘‘With Brooks Newmark we used subterfuge to prove that he was abusing his position, and there was no other way of doing it.

“We couldn’t have got a young woman who wanted to be involved in Conservative politics to go on the record and talk about it, because if you’re a young woman in your twenties who wants to be an MP the worst thing you can do is kick up a big fuss about your party in the press. If you do that, then your career’s over.’’ ‘‘I’d like IPSO to come up with an alternative suggestion of what we could have done to prove this man’s wrongdoing.’’

Another difficult aspect of the investigation is that the, in some cases explicit, photos of ‘Sophie’ that Wickham sent to Newmark were of women who were completely unaware that they were being used in this way. ‘‘I was very disappointed when those photographs were published...We did everything we could to prevent their identities from coming out, and those photos from coming out – deleting the twitter account, and stuff like that. If I were to do it again, sure, perhaps I would get the photos to have been posed, but I would say that the Sunday Mirror and myself never published the photos.’’

Wickham is part of the four-man editorial team behind the Guido Fawkes Blog. ‘Guido’ has become a force to be reckoned with in British politics, and introduces himself as “the only man to enter parliament with honest intention. The intention being to blow it up with gunpowder.” Wickham explains his motivations to me: ‘‘There’s lots of what politicians do that we’d consider a resigning issue and a political scandal, and lots of that wouldn’t get looked at by the police, or their own parties, they’d always be covered up.”

Sophie Wittams may have been fictional, but the women in politics who are subjected to such treatment are very real. Whether or not IPSO will condemn or condone this exposure of their treatment remains to be seen.

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025

News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025 Science / Did your ex trip on King’s Parade? The science behind the ‘ick’12 December 2025

Science / Did your ex trip on King’s Parade? The science behind the ‘ick’12 December 2025 News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025 Arts / Modern Modernist Centenary: T. S. Eliot13 December 2025

Arts / Modern Modernist Centenary: T. S. Eliot13 December 2025