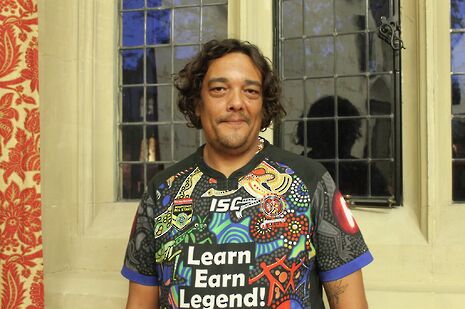

Rodney Kelly: ‘We will beat white supremacy and make Australia a better place’

The activist for the return of the Gweagal spears, currently held by Trinity College, talks to Jess Ma about his ongoing fight to restore his ancestral culture

In the past four years, one lone Australian man has returned time and time again to Cambridge to protest the return of his ancestral spears. The Gweagal spears are currently held by Trinity College and housed in the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Filling the dimly lit room in the Old Divinity School with heavy sombreness, he speaks of the persistent legacy of colonialism and oppression on his people, argues against refusals for repatriation, and lets the echoes of his didgeridoo plead the rest of his case.

This man is Rodney Kelly, a direct descendant of the Gweagal people of Botany Bay in New South Wales, whose spears and shield were seized by Captain Cook during his landing in Australia in 1770. This fateful encounter opened the colonial chapter of Australian history, and marked the beginning of centuries of injustice for the Aboriginal people.

Sitting down with Varsity after his talk, Kelly opens up on his past efforts, the growing movement of art repatriation, and the decolonisation movement.

Growing up in a reserve in Australia, Kelly’s idea for his campaign began when he “realised that there is more than just living here [in the reserve]” and that he was “old enough to start thinking about who I am and where I come from”. Starting from family stories, he quickly delved into historical papers and research about his people’s history to find out more. Finding out coinciding facts on that fateful day from historical papers and oral history in his family, Kelly quickly became determined to “do something for his ancestors” as the sources he read confirmed that the spears and shield that Captain Cook took belonged to his ancestors. For him, recovering the Gweagal spears means more than the affirmation of his, and his family’s, identity and place in Australia. The spears represent a “healing process” to reconcile Aboriginals and the colonial legacy in today’s world.

Ever since Cook’s conquest of Australia, Aboriginals have suffered from discrimination and maltreatment that still persists today. In the December quarter of 2018, 28% of full-time adult prisoners in Australia identified as Aboriginal and Torres Strait islanders. The Australian Reconciliation Barometer survey in 2018 concluded that 33% of aboriginals and Torres Strait islanders have experienced at least one form of verbal racial abuse in the past six months, while 51% of Aboriginals and Torres Strait islanders respondents believe that Australia is a racist country, as opposed to 38% of the general population.

“True history is not taught in Australia, that’s hidden and is kept secret. I know that the spears can bring that [Aboriginals’ place in Australian history] all out in the open so people might understand who we are," Kelly says. “Back home everybody always tell me that there is so much teaching to do. They could tour Australia and teach the young about everything in our culture, and how we were treated, and how we are still treated today. That’s what I really believe will happen once they [the spears] are returned.”

“[As] we learn more and more of that, we will beat white supremacy and make Australia a better place.”

Kelly’s speech is punctuated with mid-sentence pauses and heavy stares at the table below him when he recounts the situation for Aboriginals and the hardships in his campaign. He describes his annual journeys to Cambridge, as well as other European countries where Aboriginal artefacts are held, as “very hard”: he faces disappointment when confronting museums which refuse to honour his requests, and a lack of general interest from the public.

"No matter what I think, no matter what I feel, it doesn’t really matter because I know I’m laying this path for the next generation"

Stressing that he is trying to “answer without being angry”, Kelly says frustratedly that he initially “thought no one in Cambridge cares, nobody cares about him [me], so what am I doing here? Nobody goes up to see him, nobody wants to learn about him” He tells of one instance when he was trying to attract attention to his campaign by playing the didgeridoo, an Aboriginal musical instrument, on the streets of Cambridge for a week, but only two people came up to him with any interest. “I thought people would want to stop and listen and then want to know more about it, but I’ve sat out there and had nobody look or bother with me playing the didgeridoo, and that has affected my thoughts, you know, that nobody cares what I’m doing.”

Loneliness also permeates his journey, even when support is beginning to accumulate both at home and in Cambridge. Kelly says that his loneliness comes from the distance from home and the persistent feeling that he is in this fight alone. Over the years, Kelly’s campaign has received increasing support after successfully pushing for legislation recognising the Gweagal people’s ownership of the spears in the New South Wales parliament and the Australian Senate, efforts which were covered by international media.

Having campaigned in Cambridge for four years, Kelly now has a network of friends and a growing number of supporters that he is glad about. “It’s getting better every time I come back to Cambridge so I don’t get that feeling no more.” However, the sense of loneliness never dissipates. As Kelly ventured further to Sweden and Germany, where his campaign was lesser known, “that’s when it all gets to me again, that feeling of being alone”.

"I want other cultures to stand up, like myself, and not worry about what they say [...] just stand up and reclaim our history that was wrongfully taken"

“No matter what I think, no matter what I feel, it doesn’t really matter because I know I’m laying this path for the next generation [and] other indigenous cultures. I’m laying this path down for them, so if I don’t get results, I know someone is going to get results one day, and that’s what keeps me going.”

Kelly’s visit to the British Museum in 2016 saw links sprout between his campaign and others of the same cause. He said that people with similar concerns from other cultures have been asking him for advice and expressed interest in joining his campaign.“It’s not just about me, my people’s artefacts, it’s about all indigenous people’s artefacts. We’ve all been wronged in many ways and had many things taken. I’ve always had other cultures on my mind.”

Kelly has been participating in a “British Museum Stolen Goods Tour” organised by pressure group ‘BP Or Not NP?’, which leads protests against the oil industry’s involvement in the arts, and led this year’s tour. Kelly hopes to build on the momentum of the movement as more groups from different cultures meet. “I want other cultures to stand up, like myself, and not worry about what they say, and not worry about being alone or how hard it is, just stand up and reclaim our history that was wrongfully taken. It’s too big now, it’s worldwide.”

When asked about the University’s blossoming decolonisation movement, which is seeing marginalised perspectives introduced into the curricula of various humanities subjects, Kelly welcomes the movement and comments that decolonisation is necessary in museums and universities. “They’ve got to stop being in that colonial era of taking and being high and mighty”. He believed that this is difficult to achieve, but putting decolonisation out in the open for discussion is the way to go.

“Decolonisation, racism, they’re all connected. When we talk about decolonisation, we are talking about racism because that’s what we want to try to stamp out. Decolonisation is a way to do that, get out of that colonial mindset and era, and come to the future where you decolonise these institutions and have that relationship where racism is no more, and a person of a different skin colour is always going to be equal.”

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026 News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026

News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026 News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026

News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026 News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026

News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026 News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026

News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026