Marching on: efforts to decolonise the Cambridge curricula expand despite rising challenges

Working groups face organisational and outreach challenges as they continue to push forward their cause while new working groups are established

The past academic year has seen decolonisation efforts branch out into various faculties with the establishment of working groups and campaigns. This year, Cambridge has seen the union of decolonisation and divestment causes, more talks exploring different facets of decolonisation, as well as the establishment of new working groups in various subjects.

Law and History of Art saw the establishment of decolonisation working groups this Michaelmas.

Decolonise Cambridge Law have had some preliminary discussions to plan their course, telling Varsity that “a big part of our project as it stands is to investigate in what ways and how far to decolonise our understanding of law”.

“What we want to achieve is not some ideal Decolonised law syllabus, but maybe it is the mindset of students that we want to change – to learn the law with a more critical, questioning attitude,” they said.

Next Michaelmas, the Group hopes to “launch a series of regular talks, as well as a regular reading group spearheaded by graduate students.”

Decolonise History of Art and Architecture aims to “look out for neo-colonial practices in subject curriculums and also attitudes within the faculties” and raise awareness on the “heritage of colonialism” in the subject.

The group has begun talks with the Department, with suggested adaptations to include a wider range of voices on the curriculum and feedback on the hiring of a new staff member.

“History of art and architecture is beginning the process of doing that and we are doing lots of things to decolonise the curriculum as well as our own understanding of art history. We have already achieved changes to the curriculum these may be small but every success is significant.”

The group has also invited Rodney Kelly, an advocate for the repatriation of the Gweagal Spears, which are indigenous artefacts seized by Captain James Cook on his landing on Australia in 1770, to give a talk.

Meanwhile, as working groups strive to raise awareness on campus and push for progress in faculties and departments, challenges emerge on the fronts of organisation and outreach. Targets of decolonisation action encompass a wide spectrum of students and staff, each with different concerns and focuses, yet most of the efforts are centred on campaigners on the working group. Both Decolonise POLIS and Decolonise Anthropology, which were established last year, face challenges in harnessing their forces to reach as many disparate groups as possible.

Yi Ning Chang, a second year HSPS student, told Varsity that the Decolonise POLIS (Department of Politics and International Studies) working group was set up by several third year students last year. This year, as the founders have graduated, the working group is set out to engage more academics, both staff and PhD levels, and organise more talks “to create more content for discussion for the benefit of both those who are not entirely sure of what decolonise means and those who are interested in knowing more”.

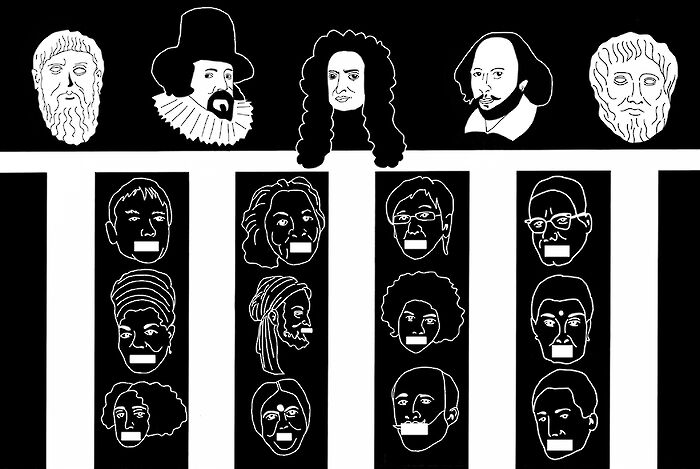

In the past two terms, Decolonise POLIS has organised a series of “Brown Bag Talks”, informal lectures where academics who have an interest in decolonial and postcolonial topics share their research. The talks encompasses a wide range of topics, from the relationship between anti-immigration rhetoric and public opinion to linguistics. Chang highlighted that the talks are meant to “transgress disciplinary boundaries” to redefine what constitutes politics and what doesn’t, as part of the effort to bring in marginalised or silenced perspectives.

The group has also been engaging in meetings with the Faculty, focusing mainly on changes to the undergraduate curriculum. Chang emphasised that even though there has been “a level of consistent engagement between June last year and now”, the working group would like to see more interaction with the Faculty as the level of engagement is “not as much as we would like”.

The group has attended feedback meetings organised by the Faculty, bringing in ideas gathered from a focus group with mostly first and second year students, as well as a list of specific suggestions from the working group. Chang said that the Faculty “mostly listened and did not speak much” upon the suggestions.

In running the group, Chang said that one challenge was to “speak across different levels” as the group is trying to have a broad reach across the faculty, from undergraduates to the Faculty. She explained that it is difficult to reach everyone as the concerns are different for each group, such as undergraduates focusing more on the curriculum and PhDs on funding, hiring, and research support.

She believes that finding commonality between the groups helps to tackle the challenge. For instance, discussing about decolonisation in supervisions helps to involve the faculty, and both postgraduates and undergraduates. The Brown Bag Talks “has managed to bring different levels together, and the undergraduates can learn from the postgraduates, and hopefully the other way round as well”, Chang added.

Chang believes that there should be more interactions between the working group and the Faculty to instigate institutional change. “It’s not hard to do things outside [the institution], the Brown Bag Talks are a representation of our efforts to do that. But if we want institutional change, like the reading lists and syllabus, a lot more needs to be done both ways,” Chang concluded.

Meanwhile, Thandeka Cochrane, a fourth year PhD student in Social Anthropology, talks of unforeseen organisational challenges in running the working group.

Similar to Decolonise POLIS, Decolonise Anthropology Cambridge saw the departure of its founders. As Cochrane took the helm this year, the group has had an open meeting in Michaelmas last year, attended a joint meeting with decolonise Anthropology groups in SOAS and Oxford, and organised a few talks on the history of anthropology and its colonial relation to Africa. The Group also has “strong conversation” with the Museum of Archeology and Anthropology in organising upcoming discussions and tours.

This term, the campaign has also invited Rodney Kelly to give a talk at the Department of Social Anthropology on the Gweagal Spears, which were taken from the indigenous Gweagal people from Botany Bay in New South Wales in 1770.

However, Cochrane revealed that there is a huge challenge in organising and maintaining the working group as the turnover rate is high within members of the working group. She cited one main factor as the fieldwork requirement in postgraduate Anthropology degrees: PhD students usually undertake 12 to 18 months of ethnographic fieldwork while Masters students may undertake 6 to 8 weeks of fieldwork. Preparation for the fieldwork and work after render postgraduates unavailable to contribute, which also “makes it hard to build any kind of group”.

In the meantime, late specialisation in the undergraduate level makes it hard for the group to recruit undergraduate members. “Undergraduates only specialise at the very end, even in third year. Very few undergraduates see themselves as Anthropology [students],” Cochrane explained.

Cochrane is worried about the continuity of the group as she will be completing her doctoral thesis this year, while some other members will be leaving for fieldwork soon. “We have no time and capacity to push it at the moment.”

Looking ahead, Cochrane said that the group will focus on the history of the Department of Social Anthropology, hoping to organise critical walking tours of the Department next year. Pedagogy will be another focus where the group explores the canonical approach in curricula. Forging “a way for more consistent communication” with the Department will be another goal.

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026 News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026

News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026 News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026

News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026 News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026

News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026 News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026

News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026