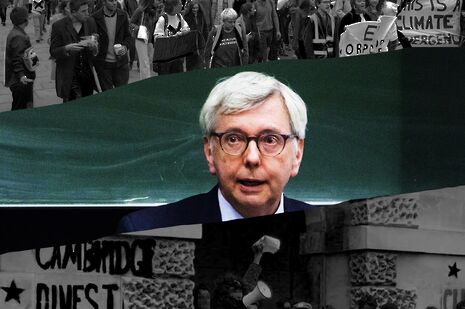

Analysis: Toope’s talk revealed the University’s true priorities

The open meeting provided some insight into Toope’s reasoning, but further indicated Cambridge’s reluctance to boldly address certain key questions

“Is the world changing? Yes. Is it changing fast enough? No”, the vice-chancellor told the group of 80 gathered in Mill Lane lecture theatres yesterday evening.

Vice-chancellor Stephen Toope, alongside Pro-vice-chancellor for Education Graham Virgo, was questioned on the University’s approach to divestment, drinking societies, and racial justice. A pattern emerged in Toope’s responses: consistently answering questions about what needs to be done with citing work that the University has already done.

Toope’s descriptions of the University’s reluctance on certain issues contrasted with his impassioned rhetoric in the previous open meeting that the Prevent duty was a “fundamental misconception”, and that climate change is the “fundamental, crucial claim of our generation”.

Yesterday’s discussion revealed a disconnect in the vice-chancellor’s approach to the issues that have dominated Cambridge’s political agenda for years: That despite his belief that the world must evolve with an urgency it has failed to realise, Cambridge, for now, is set to partake in that failure.

A stalemate on divestment

“Look at all the large universities around the world that have endowment funds, and how many of them have divested”, the vice-chancellor said, pointing out that only a handful have committed to full divestment.

Despite his previous claim that climate change is “the fundamental, crucial claim of our generation” and an acknowledgement yesterday of the global institutional stalemate in moving away from fossil fuels, Toope remained skeptical that the virtues of being a pioneer outweigh its risks. He said, on the question of whether more risk should be taken in its investment strategy: “Exactly the right question, [...] not an easy answer.”

The pace at which to divest from fossil fuels, he indicated, must take into account the rates at which other institutions are following suit. “My point is”, he added, “other people are reaching other conclusions”, after one audience member pointed to the London pensions fund, the University of Bristol, and the Church of Ireland in all having committed to divestment.

The vice-chancellor, whose remarks at the first open meeting left more questions raised than it answered, indicated yesterday the seriousness with which he takes the counterargument against divestment.

He noted that if the University divested, and as a result, lessened its endowment by 3% in 50 years for example, it would be impossible to predict what the consequences would be.

In the span of an hour, Toope both recognised the urgency of climate change, and failed to stand up as a pioneer against it.

We return to the oft-cited statement of investment responsibility at the heart of the divestment debate, updated in 2016 to reflect that there exist circumstances in which the University may balance against its primary considerations of financial return the ethical nature of investments. Toope provided little indication of how serious an issue must be for the University’s ethical responsibility to outweigh potentially negative ramifications to its endowment growth.

The push for Cambridge to be a leader in divestment has emerged as one perspective on the debate. Six days before the Council is set to make its highly-anticipated decision of whether to divest, Toope seemed unconvinced.

In the span of an hour, Toope both recognised the urgency of climate change, and failed to stand up as a pioneer against it.

A false promise of changing drinking society culture

Commenting on recent allegations against drinking society behaviour, Toope said: “This was a topic that we just canvassed very actively and quite forcefully at the last senior tutor’s meeting”, which took place last Friday. This sense of newfound urgency at what Toope described as a “live issue” follows controversy after a leaked video of a student mocking “inclusivity” at a Trinity Hall drinking society event surfaced.

Virgo elaborated on possible plans moving forward, that “banning drinking societies may just put the matter underground – sometimes I think banning is appropriate, then maybe it’s appropriate for the society to come back, but to actually identify, give it a purpose”.

Virgo’s remarks indicated his belief that it is possible for a drinking society to be reintroduced in a more inclusive form where colleges could “make sure, certainly, that it’s not just there for alcoholic consumption”, citing his own banning of a drinking society as Downing College senior tutor, before bringing it back “in its new form as a sporting society, open to all”.

Virgo’s implicit assertion that a college has the potential ability to manipulate the basic nature of a drinking society speaks to an overly narrow approach on the issue. By treating all-male drinking societies as unique in amplifying exclusivity, and by focusing on them in efforts of “changing the culture”, the University risks ignoring how a culture of elitism might otherwise manifest itself within the institution.

The issue begs the question – are we looking in the right places now?

The University has often praised its own recent efforts in addressing the stigma of sexual harassment and assault – during the open meeting, the pro-vice-chancellor for education made direct reference to campaigns launched or supported by the University such as the Breaking the Silence campaign and the Good Lad Initiative as “changing the culture” surrounding sexual harassment and consent.

The emergence of drinking societies as a key issue only this week forces the question of timing: why it took Grudgebridge launching its crusade against drinking societies to jolt senior members of the University into wanting to take action on the issue, with drinking societies not being a topic of conversation included in Senior Tutor committee minutes in at least the past two years.

The issue speaks to the intractability of “changing a culture” – the recent swarm of allegations against drinking society members points to a gaping hole in past efforts to address issues of both elitism and perceptions around consent, and begs the question – are we looking in the right places now?

Toope confined by fundamental contradiction of Prevent

“I interpret light touch to mean prioritising, in the balance, human rights concerns so that we wouldn’t, unless we had a pretty solid knowledge base, [...] refer someone to security services”, the vice-chancellor remarked when an audience member described the threat that the University’s “light touch” approach in rolling out the Prevent duty has still posed to the civil liberty of freedom of speech.

Toope’s remarks yesterday marked a significantly more developed public stance on Prevent than that expressed in the first open meeting, in which he told the chamber of attendees in Great St Mary’s that, “We’re really committed to take the lightest possible touch around Prevent.”

Toope’s stance reflected the fundamental contradiction of Prevent – can such a balance be achieved, and, more crucially, should balance even be the goal?

Two key issues in its implementation in Cambridge have surfaced: that the University has had no way of ensuring its professed “light touch” approach extends to colleges, which, as separate legal entities, have taken disparate approaches, and that even a “light touch” approach to a piece of preemptive legislation that one audience member described as “fundamentally racist”, is insufficient to combat the threat it poses to civil liberties.

A Varsity investigation last month revealed that a student at St John’s had been barred from chairing an event when she was judged not to be a “neutral person who can fairly chair the session”, after the college had checked her “speeches and texts online”.

Toope acknowledged these “chilling effects”, saying: “The very existence of the legislation that we can’t control [...] worry me a great deal”. It was telling, therefore, that he added that the “light touch” approach was “the best we can do”, noting that he will be lobbying Universities Minister Sam Gyimah MP today on the issue.

Toope’s stance reflected the fundamental contradiction of Prevent – as he said, the existence of the Prevent duty poses a threat to the right to freedom of speech. Trying to find a balance between what he himself acknowledges are two incompatibles is futile.

Toope’s remarks on the Prevent duty yesterday raised the crucial question: should balance even be the goal?

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026 News / King’s hosts open iftar for Ramadan3 March 2026

News / King’s hosts open iftar for Ramadan3 March 2026 News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026

News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026 Theatre / Lunatics and leisure centres 4 March 2026

Theatre / Lunatics and leisure centres 4 March 2026 News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026

News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026