Meet the man who made Trump

Todd Gillespie sits down with Roger Stone, the flamboyant political strategist who “will do anything” to get his candidates elected

Roger Stone’s political tricks began early. In the race for senior year president at high school, he convinced all the cool kids to back him and hired the least popular one to run against him. His career escalated quickly: not much later, at just 19 years old, Stone was hauled before the 1972 grand jury inquiry into the Watergate scandal.

Since then, he has never looked back. The veteran right-wing strategist has been involved in every US presidential election since 1972, although not always for the Republicans. He has no loyalty to the two-party system, insisting that “no one party could have screwed America up this much by themselves”. In 2012, he backed Libertarian candidate Gary Johnson against Mitt Romney, whom he calls “not only a phony but a loser”, adding that he is sure Romney is gunning for Utah’s open Senate seat in order to challenge Trump for the Republican nomination in 2020.

Stone’s personal political beliefs are certainly principled, and his libertarian slant puts him at odds with much of his party: he has long been in favour of legalising marijuana and been a supporter of gay marriage. This is despite the fact that in the political arena he is known for his backstabbing and inconsistent loyalty.

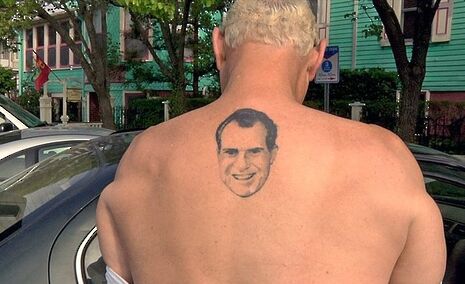

“I’m the only person you know with a dick on the front and the back”

Indeed, the loyalty he gives to his candidates is much like his sexuality – he is famously a swinger, and has been snapped at pride parades showing off his back tattoo of his idol and first major employer, Richard Nixon. “I’m the only person you know with a dick on the front and the back,” he jokes.

When he is clothed, Stone tends to dress colourfully, wearing suits, generally pinstripe, and often with a bow tie. He makes a cheap shot at his dishevelled political foe: “You’ll never mistake me for Steve Bannon.” Characteristically, Stone rips into Bannon for taking credit for Trump’s success, insisting it is his old friend, rather than Bannon, who has been the real chief strategist of the populist revolution.

But arguably it was Stone who, more than anyone else, built Donald Trump into a political figure. Or, at least, he would like people to think so. Their relationship has lasted since the 1980s, and it was Stone who was a key architect of Trump’s short-lived Reform Party candidacy in the 2000 election which helped destroy any chance of a the third party spoiler, giving George Bush, Jr., the breathing space to cross the finishing line ahead of Al Gore in one of the tightest elections in American history.

Before that infamous race, Stone, not known for his ethical considerations, was a partner in the political consultancy Black, Manafort, Stone and Kelly, which lobbied the US government on behalf of foreign dictators, including Ferdinand Marcos of the Philippines, and the Angolan guerilla leader Jonas Savimbi who won the backing of Ronald Reagan to fight the incumbent regime in the blood-ridden Civil War. Stone’s former business partner, Paul Manafort, who headed Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign, is now under indictment by the Mueller investigation for alleged conspiracy against the United States surrounding his ties to Russia.

Stone knows politics can be an amoral playground of dirty tricks, but unlike many others, he seems to encourage it actively. He enjoys the game, despite the fact he loses it often. He “will do anything”, he says unapologetically, to get his candidates elected – short of breaking the law, he is careful to add.

“If there’s backstabbing and manipulating, it sounds like all of you are being well prepared for a political career”

And so he seemed right at home at The Cambridge Union – the society is no stranger to political connivance, albeit far tamer (but often just as determined) than that of Stone and his colleagues. When I asked if he could draw a link between the Union and his own experiences, he said straight-faced: “If there’s backstabbing and manipulating and maneuvering, it sounds like all of you are being well prepared for a broader political career in the real world.” He seemed to have no problem with this state of affairs, as if it were a cause for revelry rather than a problem to be addressed.

Stone had strong words for one former Cambridge Union president, Christopher Steele, the ex-Varsity writer and MI6 agent responsible for the salacious ‘dirty dossier’. The collection of memos, funded by the Democratic Party, included graphic allegations about Trump’s private life and linked his allies, including Stone, to Russian officials. This “phony narrative”, Stone says, facilitated a scandal “much bigger than Watergate” by giving the FBI an excuse to launch surveillance on Trump and his advisers during the campaign which, Stone claims, violated their constitutional rights in the process.

His trip to Cambridge comes towards the end of a whistle stop tour of the UK, which has included a somewhat stale gig with John Humphreys on BBC Radio 4 (which was slated by The Guardian), where he, bizarrely, went largely unchallenged, and a trip to the Ecuadorian embassy in London. His association with its resident, Julian Assange, whom he calls simply “a journalist”, has raised eyebrows, including at the House of Representatives’ Select Committee on Intelligence. Stone attracted media attention on Wednesday by visiting the building where Wikileaks founder has been holed up for almost six years – “I dropped in my card, I don’t even think he’s there any more,” he told The Daily Beast.

He makes no apologies for his support of Assange, whom the Swedish authorities want extradited on charges of sexual assault and rape dating back over seven years, and is unsurprisingly an avowed advocate of free speech. He came a cropper in October when his expletive-ridden account was banned by Twitter after he insulted several CNN journalists for their coverage of the Trump presidency. Predictably, and tiresomely, for Stone, he won’t go down without a fight: “Early this year, I will sue [Twitter].” This is obviously a man who, like his president, loves to win.

In this university town, the small number of fans of one of his most successful candidates, Donald Trump, certainly does not include the new Cambridge vice-chancellor, Stephen Toope. The Canadian wrote last January: “It is not evident that Mr. Trump has a firm ideological or ethical compass. He seems to blow with the wind”. Stone hit back at Toope’s assessment, calling Trump “one of the most stubborn people I know.”

Indeed, the veteran strategist’s relationship with the incumbent president has certainly been rocky. In a 2008 interview with The New Yorker, Trump wryly dismissed Stone as “a stone-cold loser”, insisting that he “always tries taking credit for things he never did.” (Dozens of his unchallenged claims in last year’s Netflix documentary Get Me Roger Stone certainly add weight to the suspicion of him being more talk than action.)

Nevertheless, he was back on board for Trump’s 2016 campaign. Unfortunately for Stone, ever the agitator, his acrimonious relationship with colleagues led to unwelcome publicity, and he left the campaign less than two months after it launched. He claimed he resigned, but a campaign spokesperson insisted he had been fired.

He has cheered from the sidelines since his departure, and was certainly gleeful at Bannon’s undignified departure in August, but is disappointed at the president’s current foreign policy – especially his failure to withdraw from the Middle East.

Stone is coy about Trump’s future, appearing more as if he is avoiding the question than issuing a genuine caution against long-term predictions. He insists there is no way to be sure of Trump’s re-election, especially if the formidable Michelle Obama enters the race. He cites her recent rise in speaking engagements as a signal she may run, and claims that, if she wants to be, she will be the next Democratic nominee.

But regardless of whether the former First Lady runs in 2020, as long as much of American politics remains a gaudy, cutthroat reality show, you can be sure that Roger Stone will be somewhere nearby.

Comment / College rivalry should not become college snobbery30 January 2026

Comment / College rivalry should not become college snobbery30 January 2026 Features / Are you more yourself at Cambridge or away from it? 27 January 2026

Features / Are you more yourself at Cambridge or away from it? 27 January 2026 Science / Meet the Cambridge physicist who advocates for the humanities30 January 2026

Science / Meet the Cambridge physicist who advocates for the humanities30 January 2026 News / Cambridge study to identify premature babies needing extra educational support before school29 January 2026

News / Cambridge study to identify premature babies needing extra educational support before school29 January 2026 News / Vigil held for tenth anniversary of PhD student’s death28 January 2026

News / Vigil held for tenth anniversary of PhD student’s death28 January 2026