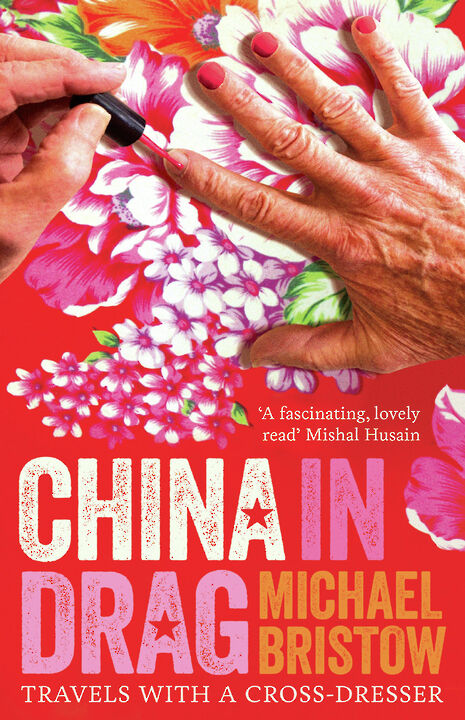

Michael Bristow: What does it mean to be a drag artist in China?

Felix Peckham talks to the BBC World Service’s Asia and Pacific editor, Michael Bristow, about his book China in Drag, which charts his journey through the country with his cross-dressing teacher

My first attempt to interview the BBC World Service’s Asia and Pacific editor is thwarted by North Korea. Michael Bristow is called away moments into our interview with the breaking news that North Korea is potentially pulling out of the Winter Olympics, hosted in South Korea in just a few weeks’ time. The BBC needs a knowledgeable mind to broadcast this news to its diaspora audience around the world. Bristow is an obvious choice, as someone who has spent eight years in Beijing as a BBC Foreign Correspondent, and who has just published a book, China in Drag, about the story of modern China and its ramifications for the wider region.

We manage to grab a few minutes between breaking news on the Korean peninsula, and Bristow gives me the endearing story of his book, though he admits it’s less his book than that of his cross-dressing Mandarin teacher: “His stories were really the stories of modern China.” Crucially, at the outset of his trip to write the story of China’s rise over the past fifty years, Bristow was entirely unaware of his teacher’s cross-dressing.

“When he got on the internet it connected him like it’s connected so many people. He found out there are others like him that he could connect with”

“On our first trip away he surprisingly revealed himself to be a cross-dresser. This is a man who was nearly sixty at the time, and its unusual enough in China anyway, particularly for someone who is a little more elderly. He was born about the time the Communists took power—his ups and downs are mirrored in their fortunes as well. I thought it would be a good vehicle to enable me to tell the story of China, so we decided to travel around to various places associated with his story. Our story became his story, and particularly that of his cross-dressing and what people said and did when we encountered them.”

Most bookshops have a healthy collection of books on modern China, especially its rapid economic development. Many have whole tables and shelves dedicated to the topic. And yet few seem to talk of the social transformations that typically accompany such a fundamental economic shift. “I don’t think there has been massive social change in China,” Bristow tells me, explaining that Xi Jinping’s Communist Party has been “obsessed with keeping a lid on any group which is outside of its control”.

While internet censorship is rife in China, Bristow asserts that the internet has, nonetheless, been revolutionary for Chinese society: “Before the internet my teacher thought he was alone — he thought that he was the only man in China who liked to wear women’s clothes. When he got on the internet it connected him like it’s connected so many people. He found out there are others like him that he could connect with, meet up, form groups with, and go to clubs. That was the turning point in his life, and I can’t emphasise enough how much of a relief that was for him, to find out that he wasn’t alone.”

“You would have an American ally right on China’s border. It wants that even less than it wants a nuclear North Korea”

Despite not naming his teacher, to protect his identity, Bristow is keen to emphasise that one of the conclusions that China in Drag reaches is that “Chinese people are actually quite tolerant when it comes to things which aren’t normally expected, such as different sexual or gender expressions — tolerant in many ways more than people in the West, which in some respects you would imagine to be more advanced”.

Few would doubt that Donald Trump’s reactionary and incoherent rhetoric has altered the power balance to some extent in the region of South East Asia. “China and the leadership is really emboldened to flex its muscles,” Bristow tells me, which is a result of China’s rapid economic growth: “China has become richer and it feels more confident. Previously it would hide its intentions or keep a low profile, but now it’s more willing to show themselves. Just this week when they announced their increased economic growth figures, the leadership were talking about a ‘New World Order’, and how the world needs China. It is increasingly emboldened, which has happened at the same time as the US has a president which has undermined America’s traditional support for freedom of speech and free trade.”

There is no more pertinent or contentious issue than that of a nuclear North Korea. The repressive authoritarian state is a political hot potato, nestled between South Korea — a staunch, heavily militarised US ally — and China, a fiercely independent foe of the ‘traditional’ Western concept of a World Order. North Korea is a complex issue for China, and is at the top of its foreign policy agenda. It is a chance for it to assert its independence and foreign policy might, but also an opportunity to strengthen diplomatic links with the US and key players in their region, namely South Korea and Japan.

“There are two primary important factors for China,” Bristow tells me. “One, it doesn’t want North Korea to become a nuclear power, because that could have ramifications for the whole region—which we’ve seen with South Korea taking in more American weapons for example, which China feels threatened about, and this could lead to an arms race which would destabilise the region. North Korea’s nuclear weapons could even threaten China at a later date. So they aren’t happy about that.

“But what it’s less happy about is the unification of North and South Korea which, in effect, wouldn’t be a unification but would be South Korea swallowing up whole North Korea because it’s just a basket case in terms of economic development. And you would have an American ally right on China’s border. It wants that even less than it wants a nuclear North Korea. So, at the moment, China is unwilling to completely cut ties with North Korea. At some point in the future that balance might change.”

From the giant and complicated state of China, to a giant and complicated corporation, I ask Bristow about his employer, the BBC, and its reputation abroad: “It might come to a surprise to people in Britain how much the BBC is respected across the world and it really adds to Britain’s soft power. We are a tiny nation but we have some cultural aspects which allow us to get a punch above our weight in terms of our impact on the world.” Despite recent controversies over pay inequality, for example, Bristow is keen to defend the ‘brand’ power of the organisation, emphasising that the BBC is ‘trusted’ and respected for doing its “best to give as impartial news as possible, to try to get the truth and to reflect opinion”.

“Journalism is fascinating because you get to see all aspects of life.” I can’t help but wholeheartedly agree with Bristow. It would seem difficult not to feel this way about the profession having travelled around one of the most exciting and complicated nations in modern history, with a cross-dresser, tracing changes in attitude in a traditionally conservative society

Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026

Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026 Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026

Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026 News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026 News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026

News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026 Fashion / The evolution of the academic gown24 February 2026

Fashion / The evolution of the academic gown24 February 2026