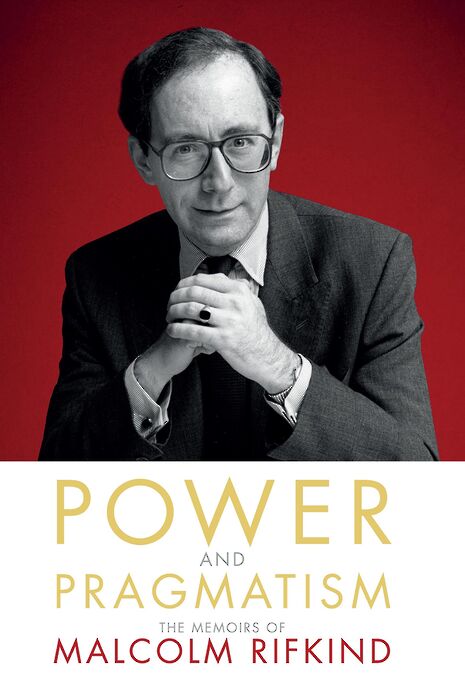

Sir Malcolm Rifkind: power and pragmatism

Josh Kimblin meets the former Foreign Secretary to discuss Britain’s place in Europe, past and future

As a visual guide to the last forty years of British politics, Sir Malcolm Rifkind’s office is difficult to beat. The walls are punctuated with photos of past cabinets and, in the corner, sits his ministerial box. As one of five Ministers to remain in office throughout the 18 years of the Thatcher and Major administrations, serving as Defence Minister and Foreign Secretary under the latter, the photos are suitably numerous.

I’ve come to hear Rifkind’s reflections on British relations with Europe, past and present. The date of our meeting, 22nd November, is significant: it is Budget Day, but also the 27th anniversary of Thatcher’s resignation – he “remember[s] the day vividly”.

We begin with the past. Hoping for an insider’s perspective, I ask how the decisions taken during Rifkind’s time in office, including the creation of the single market and the Maastricht Treaty, contributed to the broader rise of Euro-scepticism within the Conservative Party.

“These were important events, certainly,” he agrees. “But their causation relates to a much more existential question about what kind of union the EU intended to be.”

“The fact that the Conservative party moved from one view – pro-Europe – to a Eurosceptic position did not happen in a vacuum. It wasn’t an internal Conservative wrangle; it reflected the dynamic towards ‘ever-closer Union’.”

“When we joined, it is perfectly fair to say that the British should have realised that the European Community wasn’t static. Nobody could have predicted how far and how fast it would go towards an integrated Europe, although the likely direction was never in doubt.”

“But that was not how it seemed – nor how it was sold – to the British public at the time.” As he points out, Wilson and Heath agreed to “a trading organisation but not an incipient United States of Europe.”

“Since then, the UK has always measured its success in Europe by its opt-outs: from the single currency, from Schengen, from a European armed force. On balance, I took the view that the benefits outweighed the disadvantages; others argued that it was unsustainable.”

“The European Union was designed to fix something which was never broken in Britain”

This is a clear analysis. However, if Euroscepticism can be found across Europe, why did it find such dramatic articulation in Britain? To answer, Rifkind offers a reflection on Britain’s longer-term relationship with Europe, rooted in the differences between the British and continental experiences of the past century.

“For most of Europe, the twentieth century was a lousy century, with two World Wars, communism, fascism and Nazism,” he begins. “Democracy and the rule of law have been fragile. Membership of the EU has been seen as an insurance policy for Europe’s democratic institutions; you surrender part of your sovereignty to strengthen those values.”

“The United Kingdom has these values but sees no need to insure them. We have not been invaded for a thousand years. Unlike every other continental country, except perhaps Sweden, our rule of law system has not been threatened since Oliver Cromwell. Our distinctive experience has given us a sense of identity... the European Union was designed to fix something which was never broken in Britain.”

Rifkind’s analysis identifies pragmatism as the central tenet of British foreign policy – a principle incorporated into the title of his memoirs, Power and Pragmatism. “The British view is that we share sovereignty where there is obvious benefit,” he explains, pointing to the creation of NATO and the single market. “What we don’t do is share sovereignty for idealistic reasons, or for a great vision of a united Europe.”

If we extend Rifkind’s thought process, which implies a ‘deep narrative’ behind the surface details, then another feature of Britain’s relationship with Europe becomes apparent: every time Britain has withdrawn from continental affairs, it has become involved again. Is this a trend which we should expect to continue post-Brexit?

“It’s a good point you raise and it’s very relevant,” he acknowledges. “Despite being an island, whenever Britain has seen European stability threatened by one state or another, it has not only sided with those threatened, but chosen to be militarily involved.”

“It started with Marlborough, at Blenheim; it continued with Napoleon. In neither case were we physically threatened with invasion: most of the continent would have been happy if we’d remained neutral. But, far from being isolationist, we took the view that if Louis XIV dominated Europe, if Napoleon dominated Europe, or the Kaiser, or Hitler, or Stalin, that threatened us as much as it threatened continental European countries… Britain has never had the isolationist aspiration which the Americans occasionally yearn for.”

“Britain has never had the isolationist aspiration which the Americans occasionally yearn for”

This analysis would leave historians spluttering with caveats but it is quite persuasive. Cheekily, I ask whether he agrees with the Yes, Minister dictum that, for 500 years, Britain’s foreign policy been to create a ‘disunited Europe’?

“These are marvellous lines,” he laughs, “rather like Lord Ismay’s comment about the purpose of NATO being to ‘keep the Russians out, the Americans in, and the Germans down’.” Ever the politician though, he adds that Sir Humphrey’s characterisation is “a gross parody of reality”.

Turning to the present, Rifkind strikes an optimistic tone about the long-term trajectory of British relations with Europe. “We still have a strategic, geopolitical interest in working extremely closely with those in Europe who want co-operation.”

When I ask how this co-operation might proceed, he points to the precedent of including Germany as part of the Iran nuclear deal. “When the Iran negotiations were handed to the P5 nations in the United Nations Security Council, those states agreed that Germany had to be included to make the approach credible. So it became the ‘P5+1’. The equivalent we need is an ‘EU+1’.”

“We have the most important military capability and most important intelligence agencies in Europe. Our defence budget is the largest. These are assets for Europe as a whole, if it chooses to use them.”

So will the long-term diplomatic impact of Brexit not be as great as many currently assume? Rifkind demurs: “I would put it slightly differently – I think it need not have a large impact. If there is a mutual interest then, once we get over the rhetorical differences and initial hurt over our departure – and hurt is a better word than anger – then the substantive foreign policy issues should be resolved quite easily.”

Rifkind is a master of fine distinctions and diplomatic phrasing: given the tenor of the Brexit negotiations, the phrase “rhetorical differences” seems like an understatement.

However, his recognition that the fall-out from Brexit “need not” – but might – be exaggerated relates to a broader shift in Britain’s diplomatic outlook. Whereas Rifkind’s brand of diplomacy is pragmatism personified, his incumbent successors are driven by almost entirely ideological convictions.

Tellingly, one of his few critical comments is directed at advocates of the ‘no deal is better than a bad deal’ argument. “There are some prominent backbenchers who do not currently carry responsibility for policy and are therefore at liberty to propose ideal alternatives which nobody seriously believes are tenable.” He mentions no names.

As I thank him for his hospitality, it is difficult not to wonder whether current politicians ought to take a leaf from Rifkind’s textbook of discretion and pragmatism

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Comment / League tables do more harm than good26 December 2025

Comment / League tables do more harm than good26 December 2025 News / Girton JCR publishes open letter expressing solidarity with Palestine25 December 2025

News / Girton JCR publishes open letter expressing solidarity with Palestine25 December 2025