How CUSU lost about £300,000 in three years

Analysis: Bad contracts, poor management and putting all its eggs in the same basket have rocked the student union’s finances

Update: CUSU has changed its story on whether it expects future publications, contradicting earlier statements. An updated article can be found here.

CUSU has suffered massive losses to its financial reserves as a result of difficulties exiting a publishing contract, it was revealed yesterday. While the full scale of the damage is unknown, CUSU’s manager said it may be set to lose up to £400,000 in income across four years in deficit. As the loss of publication revenue forces CUSU to mull a range of cuts, Varsity explains how things got so bad for the student union.

What kind of publications does CUSU produce?

CUSU has been involved in creating a number of careers-focused publications, notably the CUSU Guide to Excellence. Recent productions – the latest of which is a website called Cambridge Strategies which combined an eBook, website, app and marketing campaign – have been made in partnership with a company called St James’ House (SJH).

The eBook consists largely of advice for graduates on entering the marketplace, and includes a foreword by former CUSU President Priscilla Mensah. The various publications often contain paid profile spots for hiring firms or educational institutions, with Cambridge’s international prestige used a selling point.

CUSU has had a business relationship with SJH for the last eleven years, but careers guides like the Cambridge Careers Handbook (later The Oxford & Cambridge Careers Handbook), and various freshers’ guides have been at the core of CUSU’s revenue stream since the late 1980s.

Increasingly, members (i.e. students) have questioned their value. In 2014, noting that print revenues were declining, CUSU set an aim to diversify its income.

What went wrong?

Following member feedback and its own diversification strategy, CUSU began to detach itself from its existing contract with SJH. In May 2015, CUSU sought a bailout from the University of £100,000, mostly for money lost by cancelling the Guide to Excellence. With the student union facing a £67,000 deficit, and needing to cover the costs of essential services, the University paid up.

There appears to have been a miscommunication at this point. Despite minutes from the University stating that “support for this request should be regarded as exceptional”, CUSU operated under the belief – stated by current President Amatey Doku on Monday – that they would annually receive £60,000 to cover losses as it transitioned away from focusing on publications.

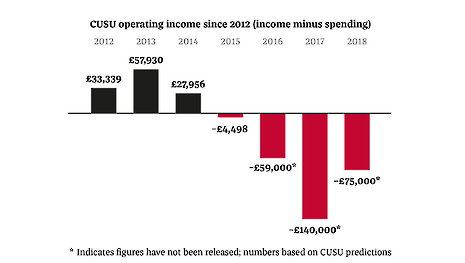

That was not the case. The University gave the payment as a one-off, and since then, CUSU has been hemorrhaging money as it runs repeated deficits due to low income. Last June, Varsity revealed that CUSU had posted a £4,498 loss in its most recent annual accounts, for 2014–15, mitigated by the bailout they had received. The loss brought the student union’s financial reserves down to £341,339.

In addition, CUSU President Amatey Doku last night claimed that SJH bore a share of the responsibility, alleging that the company has failed to punctually deliver on publications, further damaging CUSU’s ability to predict its income.

What happened then?

The loss revealed last year, it turns out, was just the tip of the iceberg. CUSU’s draft budget for 2017–18, which was circulated to Council members late on Sunday, predicted losses of £75,000 for the upcoming year, and proposed a range of cuts. It included an estimate that the value of CUSU’s reserves would drop from a new figure of £169,443. Comparison with the figures from 2015 showed that the value of the reserves had dropped by over £170,000 in two years.

Challenged on the disparity by Varsity at CUSU Council yesterday, CUSU General Manager Mark McCormack – who is contractually obliged not to speak to press, but has for the last year appeared at budget-focused council meetings – admitted that once the accounts for the last two years (2015–16 and 2016–17) came out, they would includes deficits of around £59,000 and £140,000 apiece. If it had not received a bailout from the University in 2015, CUSU’s reserves would be down about £300,000 at this point.

Without specific income projections for SJH publications available as part of CUSU’s budgets, it is not possible to tell exactly how much money CUSU has lost. Asked yesterday by Wolfson College’s External Officer, Sebastian Wrobel, whether any other student union activities had contributed significantly to the substantial losses, McCormack said that the only other way in which CUSU had lost money was due to variations in its rent costs. This appears to be a moot point: for the last three years, at least, the University has always given CUSU a block grant (called the ‘premises allocation’), which matches their rent costs. So when CUSU’s rent rose to £86,000 a year, in 2015/16, they were given that amount by the University. This means there is no reason to believe that extra losses from rent are actually a factor.

Assuming CUSU would have made a profit each year including income from the publications (as it is did for four years up until 2015), the student union will have lost something in the region of £400,000 in total by the end of the next financial year. It is not known whether CUSU pays any kind of advance deposit on the publications, or if their non-appearance only means a loss of income.

Can CUSU get its money back?

The outlook is not good for CUSU. At Monday’s Council meeting, facing repeated questions from Council members and the student press, Doku and McCormack expressed little confidence that the money is likely to be recovered. The specifics of the contractual relationship between CUSU and SJH are unknown, but the CUSU representatives said that there was no fixed time period within which SJH was obliged to produce publications, and suggested there was no automatic refund policy in the event that a publication is delayed. Doku expressed scepticism that future publications will arrive at all, saying he did not know if they are “in the pipeline”.

What happens now?

Amatey Doku presented a suite of nine cost-cutting measures for the following year to Council on Monday. They include staffing efficiencies, as well as looking at cutting the cost of CUSU’s website. A rise in affiliation fees is also on the table.

CUSU is left significantly financially damaged, and faces continued losses over at least one more year. Its reserves have diminished, and will be nearly a quarter of their previous size by the end of the next financial year. The incident is likely to further damage CUSU’s often-fraught relationship with the University, who CUSU are likely to now have to go for a fresh bailout. CUSU has said that it will still try and pursue publishing contracts in the future.

What other repercussions will fall upon the student union are as yet unknown. The figures are a damning blow for Mark McCormack, whose responsibilities as CUSU General Manager include ensuring financial continuity across rapidly-changing sabbatical officer teams, and for CUSU’s Trustees, who oversee the student union’s operations.

Under CUSU’s ‘Staff and Student Protocol’ – which prohibits public criticism of staff by student union members – McCormack is shielded from being directly held to account for the student union’s financial troubles. The protocol says that any complaint which specifically mentions a member of staff is required to be handled first by the CUSU President, then by the Board of Trustees if no satisfactory conclusion is reached. It says that “Where student members fail to abide by this procedure it is expected that the matter will be dealt with via the appropriate instrument within CUSU’s governing documentation and shall be considered as a harassment”.

Nonetheless, former CUSU Presidential candidate Jack Drury used his column in The Tab Cambridge today to call for McCormack’s resignation, saying “If it’s true that he is responsible for pissing away enormous streams of income, Mr McCormack should do the honourable thing and resign”. It’s unknown whether there will be further fallout, with most members of Council last night hesitant to press CUSU on the situation.

Has criticism of staff happened before?

The last time this protocol was publicly engaged was following the debate over defunding The Cambridge Student’s (TCS) print edition last Easter term. In an article for The Tab, a former TCS editor directly named and criticised a member of CUSU’s staff, who was responsible for some administrative duties connected to TCS. The co-editors of The Tab Cambridge at the time said they defended the author’s “right to criticise CUSU incompetence”, but nonetheless yielded to CUSU and redacted parts of the article. There’s a difference though – Drury claims in his column to have resigned membership, so it is not known how the protocol will now operate.

McCormack’s LinkedIn profile says that he is directly responsible for contracts within CUSU, but it is unknown whether that was the case when an agreement with SJH was first reached. McCormack has been the subject of controversy before. In 2013, The Tab reported he had enjoyed an 18 per cent pay rise of £6,500, far more than that of other staff members, which took his annual renumeration to £43,000. Since that year, the salaries of individual CUSU staff have not be made explicit in its budgets, with its most recent Trustees’ report instead saying that “employees’ remuneration falls within £10,000 to £60,000”.

Provided CUSU submits them (they are officially overdue currently) to the Charity Commission, we will get to see its updated Trustees’ reports in the coming months, which should confirm the losses McCormack spoke about. We are yet to know how many more years it will be before CUSU can shore up its finances again

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026 News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026

News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026 News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026

News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026 News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026

News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026 News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026

News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026