Braving Brexit – how will leaving the EU affect the University?

Caitlin Smith examines how the University will be affected by Britain’s departure from the European Union

Throughout the Brexit saga, members of the University community have been outspoken about their opinions on both sides of the debate. With the triggering of Article 50 last month, and the surprise general election announcement just weeks later, Varsity examines what leaving the EU will mean for the University and its students.

Disaffection

In Cambridge, the most striking feature of the Brexit process is just how strongly residents opposed it in the first place. Market Ward in central Cambridge, which encompasses eight University colleges, returned the highest Remain vote in the country in last June’s referendum. Within the University itself, pro-EU sentiment seems no less potent: prior to the referendum, over 300 academics signed an open letter in support of remaining in the European Union. This is perhaps fuelling the ardently pro-EU Liberal Democrats’ confidence of victory in Cambridge, where they hope people can be persuaded to vote to reject Brexit completely.

Funding

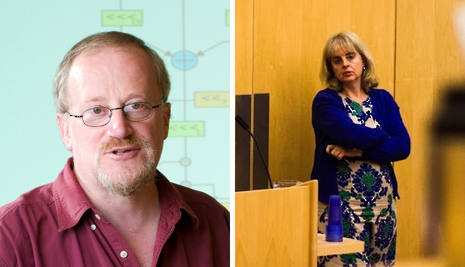

In the run-up to the referendum, Remain supporters repeatedly cited the potential financial impact of Brexit on the higher education sector, whose research projects benefit from European Union funding. In June of last year, Professor Ross Anderson, Professor of Security Engineering, wrote to Cambridge News predicting a total loss of £100 million for the University as a result of leaving the EU, including £60 million of EU funding.

Asked by Varsity if he stood by this claim in the light of recent events, he said that “immediately after the referendum, foreign institutions started freezing UK ones out” of application processes for EU grants, including the Horizon 2020 project.

He cited a report published by the Financial Times last week on a European Commission memo that the paper claims to have seen, which suggested that British institutions would be frozen out of contracts for research projects and services, even before the UK officially leaves the EU.

Anderson added, at the commencement of Brexit negotiations, “we don’t see much sign so far that higher education is a priority for Mrs May,” and suggested that the next government should focus on “keeping us in European science.”

Catherine Barnard, Professor of European Union Law at Trinity College, also identified the loss of European grant funding as a major concern for academics. Despite a recent report from the House of Commons Education Select Committee urging the government to “commit to Horizon 2020 and future research frameworks,” the government’s negotiating position on the issue is unclear.

Immigration

In her so-called Lancaster House speech in January, in which she set out her priorities for the Brexit negotiations, Theresa May expressed her commitment to protecting the rights of EU citizens living in Britain, but reducing immigration remains one of the principal, not to mention most popular, objectives of the negotiations. Her refusal to guarantee the rights of EU citizens residing in Britain until reciprocal assurances are given by Europe has done nothing to ameliorate the sense of uncertainty.

In March, the government passed the ‘Brexit bill’, but rejected an amendment added by the House of Lords which would have guaranteed residency rights for EU nationals living in the UK. The heads of 35 colleges at the University of Oxford had previously published a letter to MPs, urging them to honour the amendment.

Vice-Chancellor Sir Leszek Borysiewicz has repeatedly stressed the important contribution made by EU nationals “to the University of Cambridge’s success, to the diversity of our community, and to our values of openness, inclusion and mutual respect.” In a statement following the triggering of Article 50, he committed the University to continue to urge the government “to protect the rights of EU nationals in the UK” and to seek “assurances regarding their future status after Brexit is completed.”

Professor Anderson told Varsity that the Prime Minister had taken the referendum result as a “mandate for xenophobia,” stressing the high proportion of European colleagues in his department who were “feeling the chill.”

He suggested that, as a “global” university, Cambridge would struggle to find “hireable” staff to fill its research positions if visa regulations were tightened for EU nationals. He continued: “if we can’t get visas to hire the best people in the world, it’s hard to see how we can stay in the top three worldwide, or even for that matter in the top 50.”

Conversely, Professor Barnard suggested that it had been “business as usual” at the University in the 10 months since the referendum. She stressed that, should the negotiations fail to produce a deal on immigration, the “worse case scenario” would be a reversion to national immigration law. Even in this case, she predicted, EU nationals currently living in the UK would be offered some form of protection.

However, the prospect of hiring European staff in the future looks considerably less secure. Professor Barnard gave evidence to the Education Select Committee as part of their report, entitled “Exiting the EU: challenges and opportunities for higher education”. The report highlights a potential “brain drain” of EU academics from British institutions, should Brexit mean they are included in the Tier 2 visa system with other immigrants. Professor Barnard is quoted describing this system as “extremely cumbersome” and “highly labour intensive for universities and colleges that have to administer it.” She also issued a specific warning about the loss of talented mathematicians from Eastern Europe.

The repercussions of Brexit will not be limited to the University’s staff. While Britain remained a member of the European Union, students from European countries were eligible for British financial aid, such as loans and grants, and were not subject to the same uncapped fees as other international students. However, when asked about what funding might be available for European students post-Brexit, Professor Barnard replied “no one knows the answer to that question.” Last week, the government announced that there would be no change in the funding arrangements for European students enrolling in British universities in 2018, but the arrangements for later application cycles will depend on the outcome of the negotiations.

On Wednesday, the University announced that it was altering the names of fee classifications to prepare for any change in the status of EU students. The ‘Home/EU’ fee status will now be known simply as ‘Home’, and the ‘Overseas’ classification has become ‘Overseas/International’. In their statement, the University said that the changes had been made “so that nothing to the contrary can be implied” for students considering applying to the University in the future.

Before the Brexit process has even been completed, it would appear that EU students, who make up roughly 10 per cent of annual undergraduate admissions, already have a keen sense of this uncertainty. UCAS figures released in January showed that this year applications from EU students to the University had fallen by 14 per cent. The drop was attributed by a University spokesperson to “the considerable uncertainty felt by these students due to the EU referendum.”

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026