Lord Owen: ‘Politics is a blood sport, no use complaining’

Joel Nelson discusses Brexit, the NHS, Cameron and Blair with one of the infamous ‘Gang of Four’

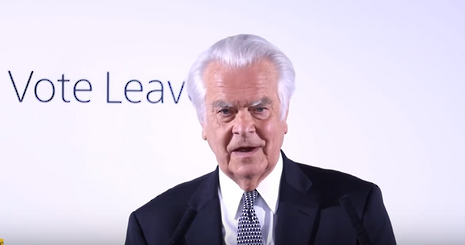

David Owen greets me at the door of his home in Limehouse, east London. The former Labour Foreign Secretary, NHS GP and founder of the Social Democratic Party – which split from Labour in the 1980s – is as enigmatic and articulate as ever, full of memories of his days at Cambridge, enthusiasm for Brexit and contempt for those who seek to delay it. We spend an interesting two hours sparring.

Lord Owen studied Medicine at Sidney Sussex College and is keen to begin by discussing Cambridge. He reminisces about E.M. Forster’s lectures, his digs on Chesterton Road, the occasion on which his landlady’s teeth fell into some porridge, the problems with the medical syllabus and the papers he most enjoyed.

“I was lucky,” he tells me. “I had a great time. I thoroughly enjoyed it. Sidney Sussex was a delightful college and I can’t praise the whole thing too much.”

Before long, though, our conversation moves to more contemporary matters. Owen, despite having long been a supporter of British membership of the European Economic Community (the forerunner of the European Union), campaigned for a Leave vote in 2016.

“What has suddenly come into British life that when you lose you suddenly think that it’s perfectly possible to reverse it?”

Why, I wonder, having been so fervent a supporter of Europe, had he become a Brexiteer? He refutes the premise of my question and is at pains to stress that he has always been an anti-federalist, recalling his youthful admiration for the anti-federalist stance of Hugh Gaitskell, the then leader of the Labour Party.

“I have remained exactly the same,” he tells me. “I have never shifted, I have never been a federalist, even though I voted with the 68 Labour MPs against a three-line whip to join in 1971.”

Owen is particularly hostile to the euro and, to demonstrate the strength of his convictions, he tells me how, in 1996, Tony Blair requested a meeting with him. “It was pretty clear what he wanted to talk about,” Owen tells me: “whether I would come back into the Labour Party.”

Owen had, however, already decided that he would not, though during the meeting, he tells me, “I almost began to think I should do this and change my mind. Suddenly Blair started talking about the eurozone and what would have been an hour’s meeting turned into a two-hour meeting and I suddenly realised how committed he was to it and how very little he understood it.”

“Everybody cheats, everybody uses every form or mechanism they can get away with”

Owen makes clear that he respected Blair until “an absolutely disgraceful episode where he started giving way to Europe on every bloody thing”. He believes that Blair was weak on Europe and expresses criticism of his indecision over whether to hold a referendum on the Lisbon Treaty – the constitutional overhaul signed by member states in 2007 – and extends his contempt to David Cameron.

“Cameron and Blair, in my view, are exactly the same,” he comments. “Neither of them are either proper Tories or proper Labour. They have got their own ambitions. They’re interested in public relations – what works, what you can get away with, how you present things – and the deeper fundamental core questions of politics, or almost anything that they deal with, are dealt with on this very superficial level. They have come to be prime minister having never been a junior minister. I can’t imagine how you can do it.”

Owen has a more nuanced view of Gordon Brown, recalling “that was a very sad period. He was clearly depressed – indecisive anyhow, but with the depression, chronically indecisive, though he did quite well during the actual crisis.”

He reserves a special level of opprobrium for those who seek to arrest Brexit. “I look at the whole thing at the moment and these debates,” he says, anger creeping into his voice, “and I say, which planet are they on? I’m only sad to see now John Major joining in this whole thing. He knows perfectly well what the procedure is. It’s a treaty. You can’t negotiate a treaty through the House of Commons.”

Drawing parallels to the EU referendum of 1975, Owen professes himself puzzled by such arguments. “I watched while Enoch Powell, Tony Benn, Peter Shore, Barbara Castle, they put everything into that [1975] campaign, they accepted the result,” he notes. “Of course they didn’t in their hearts and they came back to it in the Labour Party as soon as we lost the 1979 election but all the time I was foreign secretary I dealt with people who were dealing with the reality of the 1975 referendum. So what has suddenly come into British life that when you lose you suddenly think that it’s perfectly possible to reverse it?”

“They [the Remain campaign] had their chance,” he continues. “They controlled the government, they spent more than the Leave campaign, they had the opportunity to say in no unvarnished terms – just like [James] Callaghan and [Harold] Wilson – their case directly. They told us all these dire and horrendous consequences. As far as the fairness of the campaign is concerned, politics is a blood sport, no use complaining. Everybody cheats, everybody uses every form or mechanism they can get away with. ’Twas ever so and it ain’t going to change easily.”

Owen returns to Blair, deeply dismissive of his recent Bloomberg speech, which called for Remainers to take action to arrest Brexit. “‘Rise up’,” Owen says, quoting Blair. “Does he not realise what those words mean? Their connotations are a call to the barricades. Come on!”

He continues expressing his contempt for politicians, criticising Cameron for conducting the referendum campaign “in a hugely incompetent manner in comparison to Harold Wilson. If you believed all the crap that they talked to us about the emergency budget, the collapse of all this and everything like that if you believed a fraction of what Osborne was saying…” His words tail off and he shakes his head.

The elites, he tells me, “can’t take defeat. The British tradition is: the umpire’s finger goes up and you walk, and these people don’t know to walk. Of course, they have the right to go on doing that – we live in a free world – but is it proper behaviour in a democracy? No.”

“I joined the SDP as a Social Democratic Party, not as a Liberal Party. I feel angry that that was switched on us”

Owen is disapproving of Cameron’s decision to resign following the referendum, asking “what honesty is there? You tell everybody throughout a campaign that you’re going to stay even if you lose and on the same day you get out. It’s a strange form of relationship to the truth. No wonder people are contemptuous of them. They are utterly fed up with this kind of people. It would do huge, huge harm were they to succeed and this referendum result is upended, but I don’t think it’s going to happen and I think that we are extraordinarily fortunate that suddenly, out of the maze, came Theresa May.”

Owen insists, from his time spent talking to people in his old Plymouth constituency, that he knew the British people would vote to leave. “They just said ‘out!’,” he recalls happily. “And the way they said ‘out’ was clear that they had made up their mind a long time ago – months, years.” He was, he says, “delighted but surprised” that his native Wales voted out.

Despite the strength of his views Owen is nevertheless at pains to stress that he is no Little Englander, telling me that “I have a home in Greece and I’ve sailed into pretty well every French port on the Channel. I’m not by any means a stick-at-home, but I’ve always had this view.”

We move on to discuss the Social Democratic Party, of which he, along with Shirley Williams, Roy Jenkins and Bill Rogers, was the founder. His memories of the party, which split from Labour in 1983, before merging with the Liberals, thereby creating the Liberal Democrats, remain strong.

He is clear that “I joined the SDP as a Social Democratic Party, not as a Liberal Party. I feel angry that that was switched on us. It was a grouping that was social-democratic because that’s what its name was, and that means something. But many also wanted to merge with the Liberals. I didn’t realise the intensity of their wish to do, particularly Roy Jenkins.”

Jenkins and Owen famously fell out on this issue, with each blaming the other for the party’s failure to replace the Labour Party as the Conservatives’ main opposition. Owen still sits as an independent Social Democrat in the House of Lords but will not rule out re-joining Labour. If he were to do so it would be but another twist in a remarkable career.

Our time is almost over and I am keen to ask Lord Owen, as a former doctor and former minister for health, for his views on the current situation in the NHS. He refutes the premise of my question, once again, telling me, “I refuse to talk about the NHS in England. I talk about the English Health Service. It’s not a national health service. These guys have completely destroyed one of the best pieces of social legislation we’ve ever had in this country. My problem with Blair is not the Iraq War but what he’s done to things like the NHS. Same with Cameron.”

Anger gives way to sadness as he grimly predicts the introduction of charges. He had, he tells me, become involved with politics to protect the NHS. Now he is witnessing its destruction. It is a sad note upon which to end

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025 News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025

News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025 News / Pembroke to convert listed office building into accom9 December 2025

News / Pembroke to convert listed office building into accom9 December 2025 Features / Searching for community in queer Cambridge10 December 2025

Features / Searching for community in queer Cambridge10 December 2025 News / Uni redundancy consultation ‘falls short of legal duties’, unions say6 December 2025

News / Uni redundancy consultation ‘falls short of legal duties’, unions say6 December 2025