Transgression through a tune

Molly Taite Jupp explores the impact of protest music, considering whether it is commercial anthems or radically divisive singles that are more effective at rallying people

In a time so defined by political fracture, the prospect of meaningful change seems increasingly intangible, desperately out of reach. With hate crimes more than doubling in England between 2013 and 2019, and 322 Conservative votes rejecting the motion to provide lunches in the holidays for vulnerable children in 2020, the desire to challenge a discriminatory system feels as pertinent as ever.

Street mobilisation has led the charge as a medium for change. Nationally, the ‘Kill the Bill’ protests of 2021 amassed demonstrators in their thousands, marching in opposition of legislation which would not only increase police liberty to stop public remonstration, but which would also exacerbate the criminalisation of racial minorities and the GRT community. On a global scale too, the number of protest movements has multiplied, with more demonstrations taking place in this past decade than in any other period since WWII.

“For a song anticipating imminent 'change' however, Cooke’s image of brutality is all too familiar”

When looking at protests as a means of expressing public discontent, the impact of music – both historically and in the present day – must be addressed. One of the most accessible weapons against a dominant ideology, protest music has proven time and again its ability to unify a movement’s most powerful with its most powerless. See Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come”, written at the height of the US Civil Rights Movement. “Change” is both elegiac and expectant, an expression of pain felt by black men and women from differing social backgrounds in 1960s America. Cooke’s reference to a “brother” figure who knocks the singer “back down on [his] knees” after appeals for help is particularly poignant, exemplifying how trusted individuals, particularly those in government, repeatedly abuse their power. For a song anticipating imminent “change” however, Cooke’s image of brutality is all too familiar. Despite the half-century since its release, “A Change Is Gonna Come” is no less pertinent, both symbolising and substantiating the prolonged struggle against a white-privileging system that was made all too stark during 2020’s BLM protests.

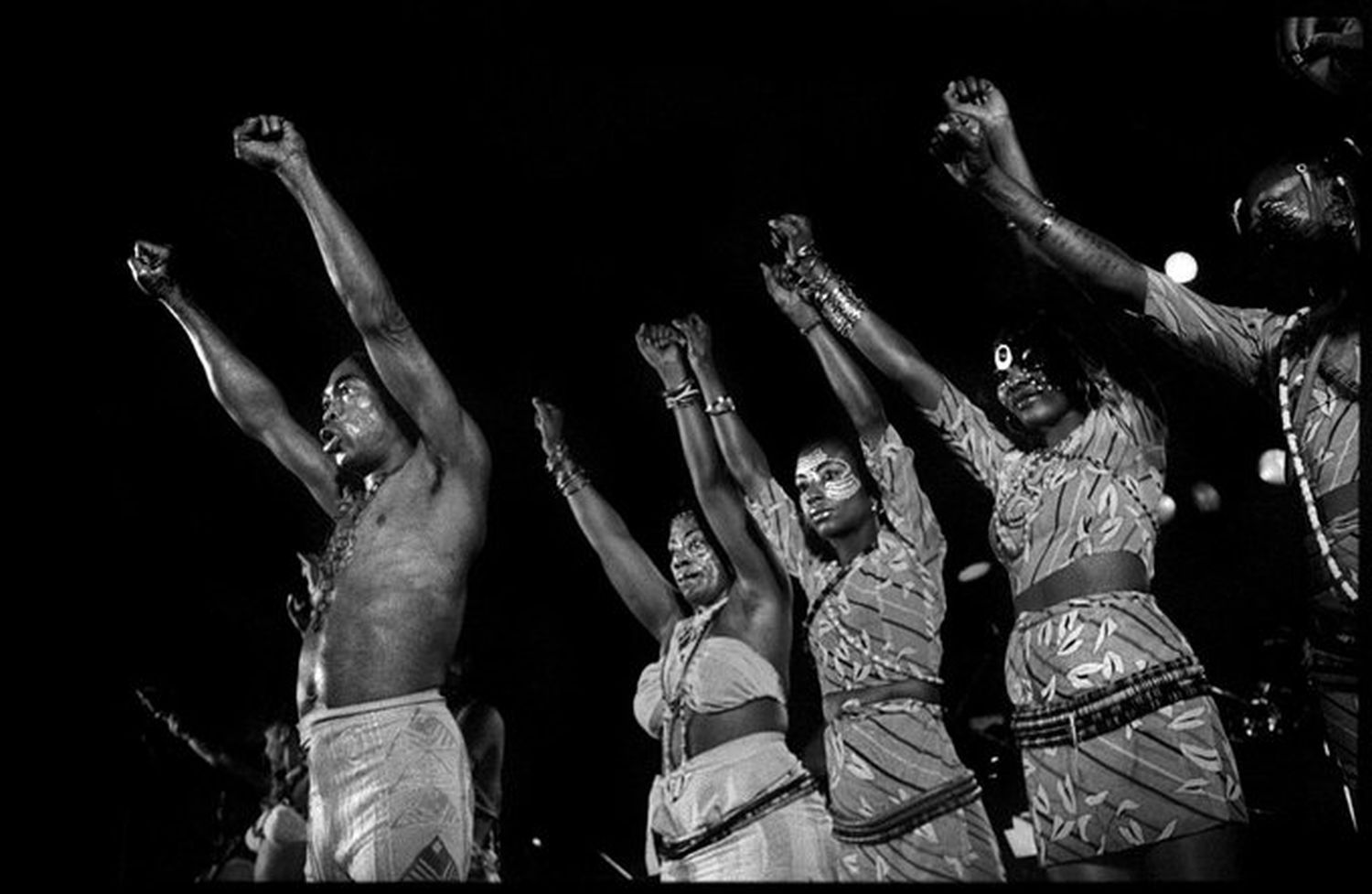

Whilst Cooke’s “Change” is almost unmatched in its durability as a protest song, music used to bolster resistant ideologies doesn’t necessarily have to endure to be successful. In the 30 years between 1960 and 1990, it was anthemic campaign songs that, in their portability and pervasiveness, were most useful in demonstrations. Country Joe and the Fish’s “I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag” is a salient example of this. With its catchiness and satirical vulgarity, it gained in popularity as a musical tirade against the American invasion of Vietnam, and was performed to “about 300,000 of you f*ckers” at the Woodstock Festival in 1969. In a similar vein, the call-and-response format of the Tom Robinson Band’s “(Sing If You’re) Glad To Be Gay” helped to concretise its message of gay pride amidst the AIDS crisis of the 1980s. Commercially, therefore, it is chant-like structures that have proven most effective in spreading transgressive ideas, unparalleled in their ability to reach not only the members of a protesting group but also, notably, the media and non-aligned public.

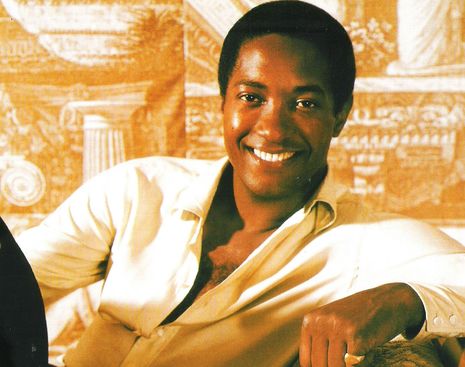

Commercial success, though, cannot always accurately measure the impact of protest music, not least because lyrical attack increasingly targets the over-commercialisation and corruption of modern society. Take Camille Yarbrough’s 1975 release “All Hid”. A damning invective against class inequality under capitalism, Yarbrough critiques the social structure which blames “the schools”, “the slums”, and, above all, the “dark and poor” for its failings. Beginning with images of those living in abject poverty, “All Hid” exposes how society’s poorest are subjected to a life of “fighting for food, for energy, for space”, whereas the upper-classes are obsessed with making ‘two-cent deals’ in ‘high rise isolation’. With the general public being disparagingly referred to as “lubricating grease for the system’s wheels”, it is unsurprising that “All Hid” could never be a billboard hit. Yarbrough attacks rather than rallies the “silent majority”, consequently sacrificing the possibility of “All Hid” taking the place of, say, Lennon’s commercially triumphant “Give Peace a Chance”. But maybe that’s the entire point? Sometimes protest songs are more about exposing an authentic expression of pain, rather than as a means of assembly.

Whether unfamiliar or practically inescapable, music plays a valuable part in disseminating subversive ideas in support of protest movements. Nonetheless, it is important to dismiss the fallacious (yet worryingly pervasive) notion of a protest movement as a mass of harmonised voices, all unified in their campaign of social justice to the tune of “Power to the People”. From the violent treatment faced by activists at the hands of police in both the Hong Kong protests of 2019-20 and the Indian Farmers’ protests of 2020-21, it is clear that, contrary to Jimi Hendrix’s belief that change “can only happen through music”, protest movements rely on the gruelling liberation efforts of dedicated participants rather than chart-topping campaign singles to incite change.

As a form of contribution to a broader societal expression of discontent, however, music is useful in bolstering social complaint. Coro Bajo Cuerda’s 1988 release “Chile, La Alegria Ya Viene” (“Chile, Happiness is Coming”) was fundamental in encouraging Chileans to vote in the plebiscite against the dictatorial regime of Augusto Pinochet, and, more recently, Gorillaz ended their seven-year hiatus with ‘Hallelujah Money’ (feat. Benjamin Clementine), releasing this anti-Trump diatribe on the day before his inauguration in 2017. Facilitating the vocalisation of oft-suppressed beliefs, protest music allows for the growth of a movement both on and off the streets, encompassing – in its very existence – a refusal to be silenced, a radical act in and of itself.

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025

News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 Features / ‘Treated like we’re incompetent’: ents officers on college micromanagement30 December 2025

Features / ‘Treated like we’re incompetent’: ents officers on college micromanagement30 December 2025 Theatre / We should be filming ADC productions31 December 2025

Theatre / We should be filming ADC productions31 December 2025