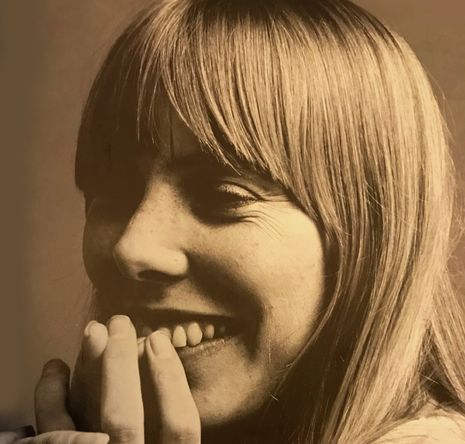

Reflections on Joni Mitchell’s ‘Blue’

To mark its 50th anniversary, Josh Osman retrospectively reviews the critically acclaimed ‘Blue’ album by Joni Mitchell

Confessional song-writing has been at the core of some of 2021’s greatest albums so far – Julien Baker’s Little Oblivions is a heart-wrenchingly raw display of her struggles with addiction, while the title track of Billie Eilish’s Happier Than Ever is a cathartic, rage-fuelled address to a neglectful former lover. With two other masters of the style, SZA and Taylor Swift, releasing (or re-releasing in Swift’s case) songs paying tribute to Joni Mitchell this year, on the 50th anniversary of her ground-breaking album Blue, the influence of the legendary singer-songwriter resonates in pop more than ever before.

“Mitchell’s raw, unguarded lyricism separated her from... stereotypically masculine rock music”

Critically and commercially successful even at its original release, Blue has often been heralded as one of the greatest albums of all time. With a striking emotional intensity bound to move any listener, Mitchell’s raw, unguarded lyricism separated her from the stereotypically masculine rock music that dominated the mainstream in the early 70s.

Beginning with “All I Want”, a tumultuous and emotional song about fully investing oneself into an imperfect relationship, she introduces listeners into her understanding and world of ‘blue’. While it begins as a symbol of sadness here, ‘blue’ develops meaning as the album continues. The next song, “My Old Man”, sees Mitchell discuss dependency as she romanticises her lover, using some of her simplest yet most striking metaphors to describe the loneliness in the absence of her lover: “The bed’s too big, the frying pan’s too wide.” Here, ‘blue’ begins to grow from mere sadness into her fears of abandonment, a theme explored in much more detail in the soul-crushing “Little Green”, a letter to the daughter Mitchell had given up for adoption, expressing her sorrow at the loss of a child, but no shame or regret.

“She pleads to either be consumed by or freed from her depression”

“Carey” is a fine showcase of Mitchell’s storytelling prowess, where she sings about travelling, and a short-lived holiday romance with an unpleasant man. On the title track, Mitchell continues to develop ‘blue’ further, writing of her depression and the ways in which people like her persevere through it. One of her most vulnerable tracks, “Blue” includes my personal favourite set of lines on the entire album: “You know I’ve been to sea before/ Crown and anchor me/ Or let me sail away” – so softly, and with such melancholy, she pleads to either be consumed by or freed from her depression.

Mitchell sings about how the feeling of isolation and loneliness in foreign countries gives her the ‘blues’ in “California”, adding further depth to this motif. ‘Blue’ becomes not just loneliness in the absence of one person, but loneliness in the absence of comfort. On “This Flight Tonight”, she tells a simpler story of growing regret, as small reminders of her boyfriend, after she leaves him behind, begin to take over, and guilt and reminiscence set in, taking over her completely.

““A Case of You” is possibly one of the best break-up songs ever written, if not the best”

Before The Pogues and Merle Haggard, Mitchell’s “River” was easily the most beautifully depressing Christmas song; in a time celebrating love, family and togetherness, she writes of her desire to escape from everything − from the reminders of the festive season, to the music industry, to her own faults that caused her to lose her love. Arguably her signature song, “A Case of You” is possibly one of the best break-up songs ever written, if not the best: with sarcasm and octave-leaping vocals, Mitchell sings of a dying love and her desperation to cling onto it, despite the pain.

Closing the album with a perfect blend of the cynicism and naïve optimism that seeps through the lyrics of the other songs, “The Last Time I Saw Richard” is a conversational song about the highs and lows of relationships ending with a rather bitter, bleak last impression. The cynic ends up in a superficial marriage, and Mitchell resents him for this, finishing the song by hoping that this period of ‘blue’ is just a phase that will pass.

Descriptions of the songs alone cannot do justice to the enchanting nature of Blue, where the blend of simple instrumentals, syncopation, personal lyricism and Mitchell’s angelic, yet dejected voice creates something much greater and more profound than the simplicity of its name can contain. Blue, still powerful fifty years later, is depression, loneliness, abandonment, and fear – a monumental album that stunningly captures the kind of vulnerability and intimacy that other songwriters could only aspire to.

Features / How sweet is the en-suite deal?13 January 2026

Features / How sweet is the en-suite deal?13 January 2026 Arts / Fact-checking R.F. Kuang’s Katabasis13 January 2026

Arts / Fact-checking R.F. Kuang’s Katabasis13 January 2026 News / SU sabbs join calls condemning Israeli attack on West Bank university13 January 2026

News / SU sabbs join calls condemning Israeli attack on West Bank university13 January 2026 Comment / Will the town and gown divide ever truly be resolved?12 January 2026

Comment / Will the town and gown divide ever truly be resolved?12 January 2026 News / 20 vet organisations sign letter backing Cam vet course13 January 2026

News / 20 vet organisations sign letter backing Cam vet course13 January 2026