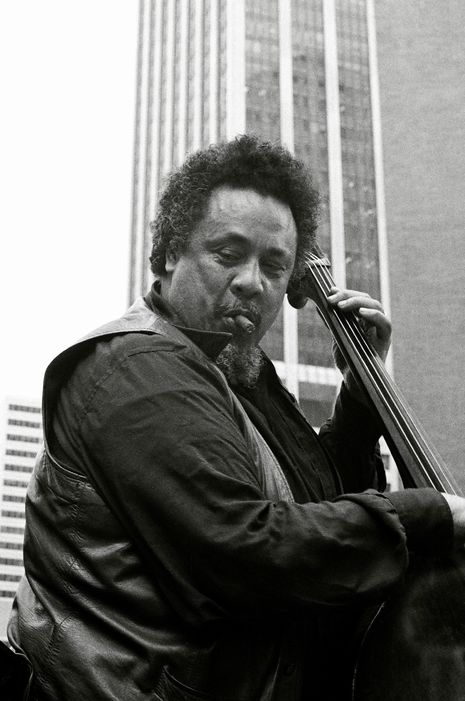

Charles Mingus presents Charles Mingus presents many marvellous faces of Charles Mingus

Tom Williamson discusses the original and diverse sounds of Charles Mingus’ 1960 album

What can one say about Charles Mingus that hasn’t already been done to death? Not a lot. In the explosion of fast-paced experimental Bebop and Jazz in the late 50s and early 60s, there’s been no figure quite as academically interesting and utterly confusing as Mingus. There are very few figures in music who can combine philosophical genius, musical talent, and out and out insanity to create such a thrilling cocktail of anger, psychosis, and utterly beautiful music that’s undeniably attractive. So instead of attempting to formulate a new academic argument, I will talk about some of the reasons that he was such a great musician, as is exemplified by his 1960 album Charles Mingus presents Charles Mingus.

Charles Mingus presents Charles Mingus runs for 46 minutes, and is unusual, since it is presented entirely as a live album, with Mingus introducing each song with requests to not clap or laugh, but also to keep one’s drink filled up - despite the fact that the only parties present at the recording studio were Mingus, regular drummer Dannie Richmond, Eric Dolphy, and Ted Curson. It opens with ‘Folk Forms’, a piece based on a repeating rhythmic pattern, stretching into 13 minutes of magnificent playing — sometimes tentative, all the players touching on each other, not sure whether to go full out on their parts lest they damage the others playing, and often magnificent: the Dolphy-Curson duet from 7:50 onward is jazz at its finest and most intense, and Richmond’s solo is superb. ‘Folk Forms’ shows Mingus’ knack for not only picking a good group, but also leading them well. Although the other parties may be playing the instruments front and centre, there’s no doubt that Mingus’ bassline is ultimately in control, and encouraging the band’s creativity. ‘Folk Forms’ also showcases the iconic Mingus vocalisations, a hollering, barking and howling that appears on the most intense pieces that just accentuate the strength of feeling and power behind pieces like ‘Folk Forms’, ‘You Better Git’ it in your Soul’ and the utterly insane cover of ‘Moanin’.

“Folk Forms showcases the iconic Mingus vocalisations, a hollering, barking and howling that appears on the most intense pieces”

Next up is the ‘Original Faubus Fables’, a loudly political piece about the “first all-American heel,” Orval Faubus, segregationist governor of Arkansas. The reason for it being the “original” version is that the actual original version, appearing on Mingus Ah Um, lacked this version’s lyrics due to Columbia’s opposition to its anti-racist themes. ‘Faubus Fables’ shows, first and foremost, Mingus’ undying and less utilised ability to create a catchy tune. ‘Faubus’ has the sombre vibe of a marching band, patterning out the reign of someone who is “sick and ridiculous”, according to the call and response from Richmond and Mingus. ‘Faubus’ also shows the intense politics of Mingus. Decrying the “Nazi fascist supremists”, and “Faubus, Eisenhower, Rockefeller”, it’s probably the finest version of political Mingus, a politics of anger (for instance, ‘Haitian Fight Song’ came from a place of “thinking about hate and persecution”). ‘Faubus’ shows his utterly superb use of lyrics, an art he perfected in ‘Freedom’: the picture, the anger, the mocking, the desperation comes across perfectly through the calls, and the use of music in both (see also ‘The Clown’).

‘What Love’ is an odd piece — it’s not one I liked at first, with little recognisable tune or time signature, but it’s one I’ve come to see as epitomising some of Mingus’ most attractive qualities. It shows his ability to adapt pieces of other musicians into something identifiably Mingus, as well as an distinctive homage (‘What Love’ is based on two standards by Cole Porter and Gene DePaul, iconic standards covered by other musicians, but rarely mixed like this). He does this better in ‘Reincarnation of a Lovebird’ and the emotionally bittersweet “letter to Duke”, but it’s illustrated very well in ‘What Love.’ However, it also shows the underlying experimental genius. Taking inspiration from Yiddish music (at least so he claimed), Mingus stopped and started his time signatures, changing the speed and the tune to the point where the envelope of not only the genre, but what is identifiable as Western Music, is pushed to the breaking point, and yet it’s still brilliant. Yet again, Mingus touches the limit of what is acceptable and comes away unscarred.

“Mingus touches the limit of what is acceptable and comes away unscarred.”

‘All the Things You Could Be by Now If Sigmund Freud’s Wife Was Your Mother’ is the final tune on the track, and it shows the key to all good Mingus, the sheer energy and insanity of the man (although it’s seen in the rest of the album too). The piece goes insane, with the musicians throwing themselves into an overwhelmingly intense riff off of the classic “all the things you are,” but without any resemblance to the original with the exception of its emotional intensity - this is brought out not in the tune, but the sheer adeptness and power of the band operating at their peak. This intensity is also seen in ‘Moanin’, or ‘Jelly Roll’, or in the Mingus Big Band version of ‘Faubus’, which I personally think embodies the spirit of the man more than any of his own recordings of the pieces.

Charles Mingus presents Charles Mingus is good — very good. But it’s probably not his best album. It never achieved the acclaim that Ah Um reached, and for very good reason: it’s an altogether catchy and adept album showing Mingus at his best both as a bandleader and a composer. But Ah Um ironically doesn’t show all Mingus’ qualities, nor does it show what makes him attractive. Ah Um is white wine music. ‘CMpCM’ is heroin music. While Ah Um is, in many parts, adept but depressingly tame, ‘CMpCM’ looks into the heart and soul of the angriest man in jazz, and shows him at his most creative, his most intense, and his most political, with the most individually brilliant moments. Mingus isn’t brilliant just because of his music — it’s the man behind the music bursting out through his artistry. It’s fascinating when, in ‘CMpCM’, you catch glimpses of the man who destroyed a $20,000 bass, a man who claimed he slept with 26 women in one night for no particular reason, the man who effectively ruined Jimmy Kneppers career with a single punch (after a recording session, Mingus broke Kneppers teeth to the point where he lost the ability to reach the upper octaves on the trombone), and yet was so much of a genius that Knepper kept working with him afterwards. ‘Ah Um’ hides this behind a Columbia polish: ‘CMpCM’ showcases the intensity, and among other things, is the reason I think it shows off Mingus the best of all his albums.

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025

Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025 News / King appoints Peterhouse chaplain to Westminster Abbey22 December 2025

News / King appoints Peterhouse chaplain to Westminster Abbey22 December 2025 News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025