Orchestra and Politics: music in the Third Reich

William Poulos explores the difficult relationship between an artist’s craft and their ideology

In July 2001 the Israeli conductor Daniel Barenboim conducted the Berlin Staatskapelle orchestra at the Israel Festival. He had included an excerpt of Wagner’s Die Walküre on the programme, but, at the request of the festival’s organisers, replaced it with music by Schumann and Stravinsky. At the end of the concert he turned to the audience and proposed a Wagner piece as an encore, saying: “despite what the Israel Festival believes, there are people sitting in the audience for whom Wagner does not spark Nazi associations. I respect those for whom these associations are oppressive. It will be democratic to play a Wagner encore for those who wish to hear it. I am turning to you now and asking whether I can play Wagner.” A heated 30-minute debate followed, in which people shouted “fascist” and slammed doors on their way out. But most of the audience stayed, responding warmly to Wagner’s music.

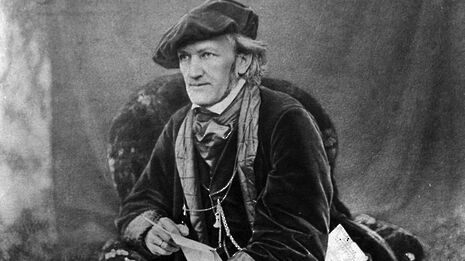

Although Israeli government-owned radio stations play Wagner’s music, a Wagner opera has never been staged in the modern state of Israel. It Is curious that Wagner, who died in 1883, is the only musical figure who is so strongly connected to Nazism that his music causes protest. Admittedly, Hitler found in Wagner’s works anti-Semitism, a strong nationalistic sentiment, and a desire for a unified German people, but Wagner had many Jewish friends and colleagues: he sent letters of gratitude to Thomas Mann’s Jewish father-in-law, who had helped build the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth.

Many musical figures had a similarly complicated relationship to Nazism. Although privately critical of Nazism and anti-semitism, Richard Strauss accepted the position of president of the Reichmusikkammer, the Nazi institution set up to promote “good German (i.e. Aryan) music”. Some biographers speculate that he took the position to protect his Jewish daughter-in-law and grandchildren, and indeed he continued to collaborate with the Jewish librettist Stefan Zweig. This collaboration caused Strauss to be dismissed from the job in 1935, two years after he accepted it.

“Attributing moral value to the music itself seems misguided”

When Strauss was made President of the Reichmusikkammer in 1933, the conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler was appointed as its Vice-President. He resigned from the post a year later but, while helping many Jewish musicians flee the Third Reich, was unable to leave it himself. After publicly denouncing the Nazis, he agreed to remain in Germany as a non-political artist with no official position. Despite refusing to contribute to Nazi propaganda, he conducted Beethoven’s ninth symphony for Hitler’s birthday in April 1942. You can find part of the performance on YouTube and see the conductor between the swastikas. After the Second World War Furtwängler said that he stayed in Germany because he felt responsible for German music, and that in a time of crisis people needed to hear Beethoven’s message of freedom and human love. There’s something to this: in occupied nations the orchestra was considered a necessity of cultural life and was (admittedly weak) proof that there was some good left in the world.

The justifications of Strauss and Furtwängler did not convince their fellow conductor Arturo Toscanini, who had become publicly anti-Fascist by the early 1930s. When Strauss became president of the Reichmusikkammer in 1933 Toscanini apparently said, “to Strauss the composer I take off my hat; to Strauss the man I put it back on again.” When he met Furtwängler he said that anyone who conducts in the Third Reich must be a Nazi. Furtwängler denied this and said that “music belongs to a different world, and is above chance political events.” Toscanini disagreed, and by 1939 had refused to conduct in Germany, Vienna, Salzburg, and his native Italy. Yet he did not believe that the music itself was intrinsically anti-semitic; during the Second World War he conducted all-Wagner concerts in America.

While you might argue that Furtwängler and Strauss – the leading conductor and composer of their day – gave the Third Reich prestige, and ought to be rebuked for it, attributing moral value to the music itself seems misguided. While Wagner was alive, Germans weren’t murdering Jews by the million. And even though Richard Strauss lived during the systematic extermination of Jews, it is Wagner and his music which are most associated with Nazi atrocities. Barenboim’s efforts at the Israel Festival tried to emphasise that Wagner’s music has been treated unfairly; tunes have no moral value. Michael Avraham, a Holocaust survivor, heard Barenboim conduct Wagner at the Israel Festival and said, ″there’s no need to link the fact that Wagner was a big anti-Semite with his music, which is beautiful… the man was anti-Semitic, not the music.″

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 News / Girton JCR publishes open letter expressing solidarity with Palestine25 December 2025

News / Girton JCR publishes open letter expressing solidarity with Palestine25 December 2025