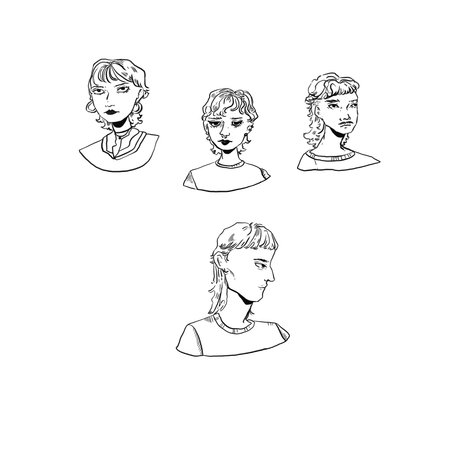

The man, the myth, the mullet.

Esther Arthurson traces the genealogy of the mullet and wonders whether the mullet maketh the man – or is it the other way round?

It is rare that something makes me wish I had never been born. However, hundreds of such reasons are currently walking our streets. Ladies and gentlemen, I regret to inform you: the mullet is back.

Made popular by the Beastie Boys in 1994, this particular form of aesthetic torment can be traced back to the 60s and beyond, including during Tom Jones’ performance of “It’s Not Unusual”. Unfortunately, he was right; the tresses trend truly caught on, booming into hairstyle history in the 70s when musical idols from David Bowie to Paul McCartney adopted the #shaggynotsorry look. Dolly Parton and Billy Ray Cyrus dragged the ’do into the 90s, the decade in which it (finally) began to die out. (Rumour has it that in Australia, due to isolation barriers and speciation, mullets are still a compulsory form of national service.) On a more serious note, the mullet was (and, I believe, still is) prohibited in Iran in 2010 due to its association with “decadent Western haircuts.” While I fully support the right to self-expression, I must admit that waving farewell to this floppy monstrosity on a national level is not unappealing.

On a note closer to home, a discovery on Wimpole Estate, Cambridgeshire, in 2018 has led historians to posit the potential category of (according to Wikipedia) ‘Mullets in Antiquity.’ The excavation of a 1st Century CE metal figure during a car-park renovation has provided incriminating evidence that our ancestors were be-mulleted as far back as the Roman occupation.

“While I fully support the right to self-expression, I must admit that waving farewell to this floppy monstrosity on a national level is not unappealing.”

Mullet CPR occurred during lockdown, with the added advantage of said mulletteers being confined to their houses – and rightly so (I never thought I’d say this, but bring back lockdown). Now they’ve escaped to torment our nation yet again. Personally, I’m all for shipping them to Australia, for old time’s sake.

I had the (dis)pleasure of interviewing a mullet-wielding specimen for the purposes of this article. He was reluctant at first, but it turns out that the back of the mullet is an excellent hand-hold, and I dragged him off the street and into the Varsity offices without any trouble at all. Unwanted tailgating is one of the many hazards posed by a mullet, it turns out, and one is at constant risk of scalping when around ‘grabby hands’ toddlers at family gatherings. Further disadvantages include: impromptu re-enactments of the skateboard seen from Back to the Future in which one (involuntarily) plays the van, not to mention the birds that frequently/regularly mistake one’s hair for home, or the cleaners that frequently turn one upside down and confuse one with the mop.I have included a summary of my findings below.

The mullet allegedly comes with a host of evolutionary advantages, from making creatures seem bigger and more intimidating to potential predators (sure you’re six foot…) to acting as a built-in helmet – in the interviewee’s words: “The mullet is its own protection.” I expect this is all too true, leading us seamlessly onto another cultural advantage of the mullet: it minimises population growth. The style can also act as a storage device for “pens and stuff” once you grow it out long enough – this particular mulleteer’s goal is to one day render his hockey bag redundant. (Tami Manis, World Record holder for longest mullet, would be proud.)

Does it impair one’s ability to perform daily tasks? The interviewee admits to being frequently held up (often literally) when his hair gets stuck in trees. However, this is somewhat levelled out by the Red Sea Effect: geriatrics cross the road to avoid him, clearing him a speedy path to lectures. Mullet? More like Moses.

I ask the interviewee if he ever speaks to the mullet. He doesn’t answer, but shifts rather suspiciously. I ask if the mullet ever speaks back: “No comment.” I had wondered why the Tangled soundtrack had been emanating through my walls recently, and now I guess I know why – “Flower gleam and glow” and all that.

My next question is whether he feels spiritually connected to fellow mulleteers, past and present. This really seems to confuse him: “Not really. Most of them are dicks. [Long pause while he thinks – an arduous process. We can only assume that the mullet has drained him of his mental powers like some sort of parasite.] No, I do actually. I see someone in the street with a mullet and think: ah, one of us. It’s like a religion, almost.” Make of this what you will, but let’s hope he follows in R.E.M.’s footsteps some time soon.

“Mullet? More like Moses.”

Following up, I request his thoughts on whether one can truly separate a man from his mullet. This is his verbatim response: “Michael Jackson was a good musician, but maybe not the best bloke. I am a good person, but I have a mullet.” I’m not sure I quite follow the sophisticated logic at play, but I nod along regardless.

Our interview is cut short by the arrival of some Stella-shooting cavemen in tank-tops, demanding I release their brother, so that’ll be all for today. May the mullet be ever in your favour.

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 Arts / A beginner’s guide to Ancient Greek tragedy16 December 2025

Arts / A beginner’s guide to Ancient Greek tragedy16 December 2025