Me, God, and the English Tripos

Reflecting on the English Tripos and her Christian faith, Cecily Fasham grapples with what to do when church leaders get it wrong.

I’m a Christian, and God is the most important thing in my life, so my faith and academic work have always been bound together. Plus, I study English, so Christianity tends to come up a lot.

In my first term at Cambridge, I actually had a head-start: I was dropped right into the medieval paper, where the texts I studied were deeply enmeshed in the period’s religious culture. Most of the time, my faith and work are entangled in mutually beneficial ways, but there is also room for conflict. I believe that God sent Jesus as his ‘Word’ and speaks to us through the Bible so, as a Christian, my relationship with language and literature has knock-on effects on my relationship with God. Texts within tripos can bring up difficult questions about religion which then have to be grappled with.

“My desire for acceptance had led to conformity instead of debate.”

My Christian Union subject group is generally a wonderfully open and honest space to explore the joys and difficulties of studying English as Christians, but on one revealing occasion, a visitor had come to speak to us. He was there to give us a schema for how to do our degrees in a way that ‘honoured God.’ Because we read the Bible believing that it is written communication directly from God, we were told to set authors up in the position of God when we read for tripos, and prioritise analysis of their original intentions. Suggesting that multiple interpretations of a text were valid verged on anti-theological in his eyes.

This threw me into a sort of crisis because my own work focuses on exploring how readers create meaning for themselves, holding no single ‘intentional’ meaning above others. I felt angry at being told I was wrong, that there was only one way to think, and was inclined to dismiss what was said. Still, underneath this, panic rose up: a gnawing fear that my work was dishonouring God, who is more precious to me than anything. In that moment, I was afraid that the visitor was right and I was wrong, and of disapproval from other members of the Christian community. The prospect of disagreement with other Christians terrified me so much that I genuinely thought about upending the principles I’d created for my academic work. I wrote about it in my weekly supervision work, and was lucky that my supervisor responded with astonishing kindness, talked it through with me, and recommended essays to help resolve the conflict. Nevertheless, my desire for acceptance had led to conformity instead of debate. The danger of following church leaders without question became clear to me in that instant.

“Medieval literature draws a dividing line between white Christians, who are worthy of respect, and everyone else, who are ‘inhuman’.”

That church leaders do get it wrong is evident from the news, where lawmakers erode the rights of women, LGBT people, and religious minorities in the name of Christianity, and prejudice is given a religious sugar-coating by conservative organisations. It is also clear in the texts we read for tripos. In my medieval reading, I have encountered a Christianity both familiar and alien; reading medieval mystics like Margery Kempe, I recognise the comforting God I know and love, preserved over hundreds of years. However, I also encounter my religion tied into racist narratives. In western medieval literature, Christianity is equated with goodness and whiteness, whilst people from other faiths are reduced to racist caricatures.

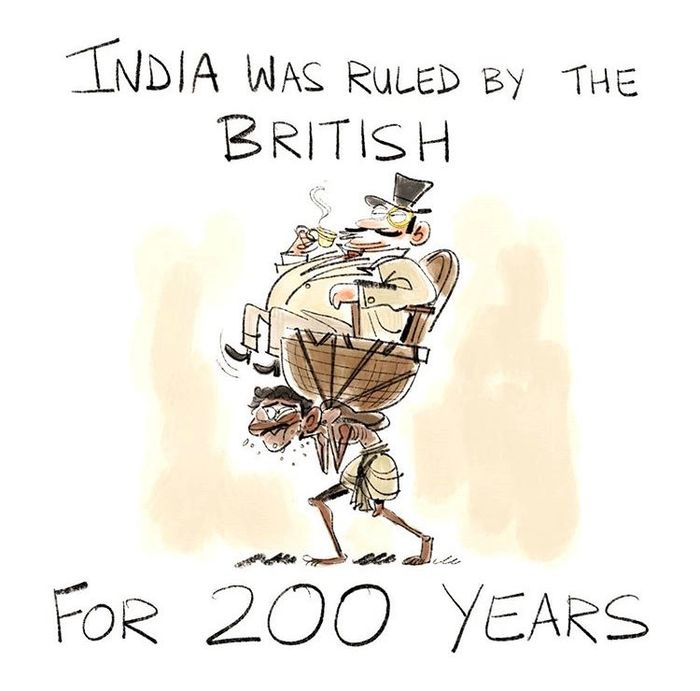

The Chanson de Roland, an eleventh century anglo-Norman crusader epic and set text for the 1066-1350 paper of the English tripos, depicts ‘pagans’ (Muslims) in strikingly racialised terms. One pagan is described as handsome, but can only be recognised as such because he is ‘white as flowers’: he would be noble, we are told, if only he were ‘Christianised.’ The crusades, and their related literature, unflinchingly dehumanised people of colour in what were essentially colonial invasions conducted at the encouragement of the church. Medieval romances present this racist binary of white-skinned virtuous Christian vs. dark-skinned wicked pagan literally and horrifyingly. In the crusader romance Richard Coeur de Lion, white cannibalism of black Muslims is presented as light humour, and in the 14th century King of Tars, a black Muslim ruler’s skin magically turns white when he converts to Christianity. Medieval literature’s racism is unavoidable – and it was implemented using religion, drawing a dividing line between white Christians, who are worthy of respect, and everyone else, who are inhuman.

“The answer isn’t to try to brush these histories under the carpet: we must confront them, and learn from them.”

16th, 17th and 18th-century literature shows a similar picture, if often more subtly shaded. As European colonisation of the Americas and southern hemisphere picked up speed, writers set out to present a benevolent image of empire: not invasion and oppression, but a compassionate mission to bring colonised peoples to Christ. Contemporary histories of colonialism were largely written by missionaries, who stress this angle. In reading these texts, once again, a struggle ensues inside me: I don’t want to condemn Christianity, because I believe in it – but I do want to condemn these narratives which use faith as a foil for bigotry. Using mission work as a cover for subjugating foreign populations takes the good news of Jesus and twists it into something I don’t want to recognise.

I don’t entirely know how to reconcile my belief in the Christian God as a force for good and love in the world, and these clear presentations of the violence that has been wrought in the name of Jesus. I do know that the answer isn’t to try to brush these histories under the carpet: we must confront them, and learn from them. What these texts show me is a mismatch between the God they represent and the God I know. Attuned to this discrepancy, I can see where my religion is used even now as a cover for prejudice, exclusion and oppression. Recently I read several 19th-century evangelical abolitionist pamphlets whose writers campaigned against slavery because of their faith in a God who made us all in His image and loves without distinction. This is the example I want to follow. By recognising the harms perpetrated in the name of my religion, both historically and in the present day, I can actively oppose them, pursuing radical love instead of judgment, and working towards Jesus’ mission to ‘set the oppressed free.’

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026 Features / From fresher to finalist: how have you evolved at Cambridge?10 February 2026

Features / From fresher to finalist: how have you evolved at Cambridge?10 February 2026 Film & TV / Remembering Rob Reiner 11 February 2026

Film & TV / Remembering Rob Reiner 11 February 2026 News / Churchill plans for new Archives Centre building10 February 2026

News / Churchill plans for new Archives Centre building10 February 2026 News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026

News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026