Do travel photos perpetuate stereotypes?

Travel photos can have be more than just a innocent Instagram, argues Lucie Richardson

With the summer holidays at an end, it is hard to avoid the deluge of holiday photos that flood the likes of Instagram or Facebook. Whether it’s mincing around the edge of a pool in a bikini, quaffing wine in a rustic Italian vineyard or enthusiastically scrubbing an elephant’s backside in a frenzied quest for enlightenment, it seems everyone is desperate to share their holiday snaps.

Far from being a recent phenomenon, sharing travel photos has been popular since the ninteenth century with intrepid travellers setting off brandishing enormous cameras and tripods. Nowadays, lightweight cameras and phones allow us to edit and share our unique perspective on a place on the go while keeping friends and family up to date via social media. No one loves a holiday gram more than myself, but I think it is also important to consider the messages we project when we post travel pictures online.

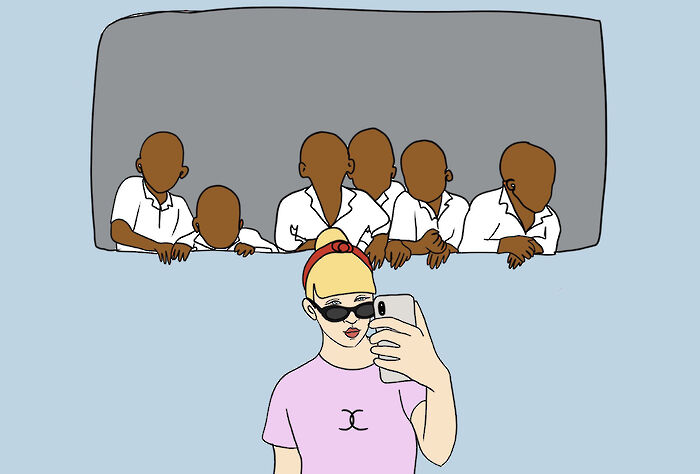

For example, the Internet is drowning in pictures of privileged people hugging small children from low income countries – though perhaps taken with good intentions, they are another example of voluntourism doing more harm than good. Such images perpetuate the myth of the privileged ‘saving’ the ‘less fortunate’, with photos of Stacey Dooley hugging a small Ugandan child reigniting calls to address the white saviour complex earlier this year.

Posting pictures of children or adults who seem weak or in need of aid reinforces the preconception that their countries are also weak. The Sir Arthur Lewis Institute of Social and Economic Studies published a paper in which it remarked how “poverty porn” representations of post-Earthquake Haiti reinforce stereotypes of the country as “an inevitably failed state”. In these images, the subjects are often patients or students on the receiving end of foreign aid placed in an environment where they feel neither confident or comfortable. Alternatively, they are erased all together. I know if people’s sole impression of me was drawn from photos taken by someone else when I was about to go for a blood test, I would have quite a different image to one I myself chose to project.

“Moving away from a culture of craving likes ... towards one of recording memories for our own enjoyment”

I sincerely advise you to avoid volunteering trips that promote the ‘white saviour’ myth– a recent Varsity article by International Development Officer at the Cambridge Hub, Folu Ogunyeye, lists some great alternatives. Likewise, if you are taking pictures, it is a basic human decency to consider how comfortable the person you are photographing is and what portrait you are painting of their country through that image.

We often forget, and I am by no means exempt here, that travelling consists of entering other people’s environment. To claim a place’s beauty spots for our social media while ignoring anything ‘not aesthetic enough for Instagram’ to me seems to be doing a disservice to the people and their home. The photos of someone passing through an area, I assume, would be rather different to someone who lives there permanently. In her TED talk The danger of a single story, author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie warns of the danger of only being exposed to stories that focus on one privileged and therefore dominant culture. The issue with only seeing the edited version of a place is that we are prevented from considering it as a whole - Adichie remarks: “it is impossible to engage properly with a place or a person without engaging with all of the stories of that place and that person.”

The beauty of social media is that you decide exactly what to post – but I always think it is worth considering what we are gaining by sharing our photos to certain platforms, for example on dating apps where people often share their voluntourism photos. Taking photos shouldn’t be a crime, but it is ultimately how we use them that renders them problematic. By using them to make ourselves look compassionate or to get dates, we are exploiting other people’s situation for our own benefit. Sadly when it comes to social media, I feel it is hard to exact change as an individual. Even if large numbers of people refuse to post pictures from holidays or volunteering trips that project a certain narrative, I feel there will still be a hundred more who have no qualms about doing so.

I was particularly struck by the impact of social media on how we travel when leafing through my parents’ photo albums. For some reason, I couldn’t help but mourn the loss of the ritual of sitting together to look at old-school albums. There is something about the un-edited nature – the goofy candids or blurry pictures from hotel windows quickly followed by a random picture of a donkey that gives a far more comprehensive sense of what these trips were like than my carefully curated Instagram. I do wonder if collectively moving away from a culture of craving likes and validation towards one of recording memories for our own enjoyment might help solve some of the problems and anxieties that surround posting travel photos online.

For example, the travel journal I made on a round-the-world trip is one of my most precious possessions, because I made it for myself and nobody else. When reading it, the constant repetition of ‘I thought’ and ‘I saw’ marks it very obviously as a single story, with events captured from my perspective on the road. I feel that recording memories for ourselves might not only help remind us that our viewpoint is singular, but also can allow us to better process our own experiences as we explore new places. After all, I think it is important to remember that our narrative when travelling for pleasure is one of privilege, and most importantly that it is not just the single story of a place but one of many.

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026 News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026

News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026 News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026

News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026 Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026

Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026 Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026

Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026