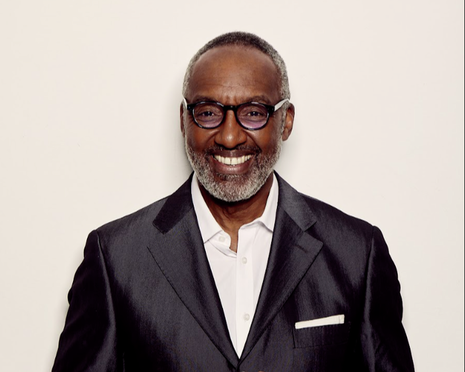

Leroy Logan: Taking an ‘Axe’ to racism in the Met

‘They’re in total denial’: former Metropolitan Police superintendent Leroy Logan’s fight for an equitable justice system

If there is one person who knows the Metropolitan Police inside and out, who has seen its negligence, its brutality, and – although admittedly difficult – its good, it is Leroy Logan. He joined the force in 1983 with the mission of bringing change from within. Despite the racism and hostility he faced, Leroy ascended the ranks to become a superintendent, founder and chair of the National Black Police Association, and a key figure in the landmark Macpherson report.

Sitting across from me, Leroy emanates warmth and energy, yet his sense of discipline and conviction are palpable – something he attributes to the brief period of his childhood he spent in Jamaica. “I saw Black doctors, teachers, police officers, so the idea was never alien to me. My parents also had a very strong work ethic; education was something that we lived and breathed.”

When he returned to London aged nine, Leroy set out to be “the best student”, eventually graduating with a degree in Applied Biology and working at the Royal Free Hospital. He worked in research, and “really thought that was it” – but his peers had different ambitions for him, urging him repeatedly to apply for the police force. He eventually came around to the idea and applied. When his father was brutally beaten up by Met officers a short time later, Leroy was distraught and enraged – but his calling only grew.

"They don’t like it when you put your head above the parapet"

I had imagined that Leroy’s day-to-day as a policeman could not have been further from his days spent in a lab, but he tells me that his scientific eye proved indispensable. “When you’re doing any sort of experiment, you never make assumptions. So as an officer, I never made assumptions based a person’s appearance, their class, or their colour. I always followed the evidence.”

Many of those he encountered did not the share the same approach. Leroy recounts having slurs graffitied over his locker, being repeatedly overlooked for promotion, and then, in 2001, being falsely accused and investigated for corruption over an £80 hotel bill from a Black Police Association conference. “I knew something was going to happen because I was chair of the BPA and involved in Macpherson. They don’t like it when you put your head above the parapet.” He took the Met to an employment tribunal and was awarded £100,000 in damages, but not before his reputation had been placed in jeopardy.

“We’ve got to keep going, keep holding those in authority to account”

A standout moment in Leroy’s policing career was his involvement in the Macpherson report – he gave evidence on the Met’s failings following the racially motivated murder of Stephen Lawrence. The subsequent report was ground-breaking, leading to changes in the law and in the police code of practice. It was also the first time the Met was found to be institutionally racist.

25 years later, in March of this year, the Met was once again found to be institutionally racist, as well as sexist and homophobic, in Baroness Louise Casey’s report. I ask Leroy what his reaction was. He tells me that at the press conference that day, he was “visibly quite animated, which I usually try to hide. I was just thinking, 25 years [...] and we’re still talking about the same thing.”

The latest head of the Met, Sir Mark Rowley, has continued the tradition of Commissioners rejecting the use of the term “institutional” to describe the force’s problems. Why has the term become so uncomfortable? “They’re in total denial. You see it daily”, Leroy tells me. “The police are the gateway of the justice system, but I saw so many people incarcerated and traumatised because of the inappropriate ways in which they use that power.”

Despite everything, Leroy’s optimism is unwavering: “you can be disappointed, but you can never be discouraged.” As our conversation ends, I ask what we can all do to encourage action. “Remember that things are never static. Change is a constant, so we’ve got to keep going, keep holding those in authority to account.”

The title of Steve McQueen’s film anthology, 'Small Axe', is a nod to a Bob Marley song: “if you are the big tree, we are the small axe”. Combining a critical eye with empathy, and optimism with discipline, Leroy is the embodiment of the axe that refuses to give in, continuing to chip away until an equitable justice system is achieved.

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026