William Dalrymple on the British Empire and the East India Company

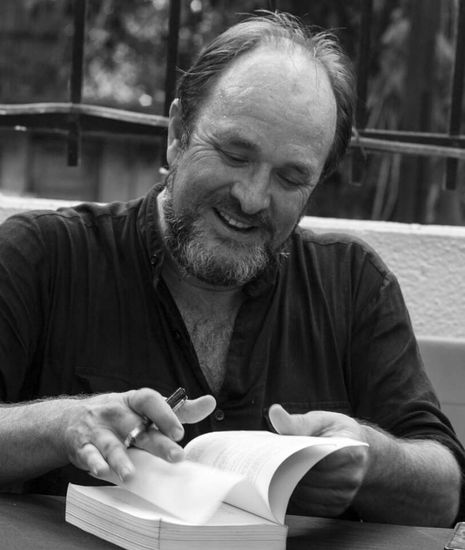

As India approaches 75 years of independence, Taneesha Datta sits down with historian and former Varsity Editor-in-Chief William Dalrymple

The first sentence of William Dalrymple’s most recent book, The Anarchy, references a Hindustani word — one that pried its way into the English language over 200 years ago: loot. Britain’s first usages of the term can be traced back to the exploits of a single London-based trading company.

At its peak, the East India Company served as Britain’s largest source of trade, and commanded private armed forces twice the size of Britain’s own standing army. In The Anarchy, Dalrymple sketches a detailed landscape of an India populated by wily statesmen and lecherous princes, ambitious accountants and hapless soldiers — and threads together the story of how a private corporation based out of an office merely five windows wide came to govern a subcontinent.

“The East India Company never pretended to be about anything except exploitation and extraction”

Over the course of our conversation, one feature of this coup crops up frequently: “The East India Company never pretended to be about anything except exploitation and extraction,” says Dalrymple. “It wasn’t ‘save the children’, it wasn’t a charitable endeavour, nor was it a straightforwardly state-run imperial endeavour. It was a for-profit corporation like Google or Walmart. It existed to make a profit, and did so very effectively, greatly enhancing the riches of this country.”

Dalrymple has spent over three decades living in and writing about India, from his first travel book - In Xanadu (1989), which was written right after he graduated from Cambridge - to his more recent narrative accounts of the emergence of British rule in India.

Yet Dalrymple believes public awareness of these issues has deteriorated since the 19th century. “The buccaneering empire-builders of the early East India Company were figures that the Victorians greatly disapproved of. There was a knowledge that the early period had been one of deep corruption and moral ambiguity, with much to be embarrassed about … but as empire has receded in the 21st century, the British by and large have just forgotten about it.”

“Even the basic fact that for over a century Britain ruled India through a for-profit corporation is something that I would suspect a tiny proportion of Brits know or understand,” he adds.

“The fact that we conquered half the globe was, bizarrely, left off the curriculum”

The culprit, he believes, is education. “The British history curriculum moves suddenly from Florence Nightingale to the Nazis, so that Britain always seems to be on the side of liberation, freeing people. You learn about the Roman Empire, the Holy Roman Empire, all sorts of empires — just not the British Empire. The fact that we conquered half the globe was, bizarrely, left off the curriculum.”

A consequence of these gaps in public understanding is a peculiar form of imperial nostalgia. In the British imagination, Dalrymple says, the Empire conjures up images of “maharajas and elephants and croquet parties, and some rather beautiful, aesthetic vision of ladies wandering across the Bangalore club lawns.”

Dalrymple has been a first-hand witness to this, and believes Brexit has only worsened matters. “I see this in India, where successive British high commissioners come out believing that India was Britain’s great ally, particularly after Brexit, with this idea that suddenly we can go back to empire and be embraced by some long-lost love and waltz off into the sunset — but it’s pure fantasy, born from a complete amnesia and ignorance.”

The most important possible tool to an understanding of the past, Dalrymple says, is visiting places and understanding what they are today. This is all the more significant as India approaches the 75th anniversary of its independence from the British Raj. “I’m very suspicious of people who write chunks of history about places they’ve never been to. It’s as vain an endeavour as writing about something without sources from all the different positions, or without trying to access both sides of the story linguistically.”

When looking to the future, he remains cautious: “With politics, it’s the art of the possible. We’re not yet at a place where the major issues like restitution can really be debated, because most people simply aren’t aware of them. It’s only just beginning to change.”

He points to the success of Sathnam Sanghera’s Empireland and Shashi Tharoor’s speech at the Oxford Union as examples of valuable milestones, but maintains that there is still a long journey ahead. “It’s not that anyone is malignly misrepresenting history, it’s just that they’ve never been taught it. There seems to be a knee-jerk reaction that this is some terrible battalion of woke traitors defaming our imperial heroes rather than a mature reaction to real history. But I think if you have even a basic factual understanding of the history, it’s very, very difficult to interpret matters in any other light.”

“It was very much at Cambridge that I read, for the first time, the history that I am now writing”

Before our Zoom call ends, I ask Dalrymple about his years as an undergraduate at Trinity College. He speaks fondly of Cambridge, recalling the inevitable post-finals lassitude (“as though the blood had been drained from one’s body”) and his time as Varsity’s Editor-in-Chief (“Stop press, we called it in those days, and we used to have these all-night paste-ups before computer times”).

“It was very much at Cambridge that I read, for the first time, the history that I am now writing. It was also Trinity travel grants that paid for my initial trips abroad. That, in a sense, was money well-invested because it got me off to these places, made me fascinated with them, made me fall in love with the history and the art and the architecture, and kept me propelled in that direction.” Here he pauses and chuckles. “Without any of that I might have ended up as a doctor in suburbia, who knows.”

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026 News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026 News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026

News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026 Theatre / Alien Breakdown Play is a promising extraterrestrial experiment 8 March 2026

Theatre / Alien Breakdown Play is a promising extraterrestrial experiment 8 March 2026 Arts / From pupil to poet6 March 2026

Arts / From pupil to poet6 March 2026