The politicisation of film and TV: pioneering or polarizing?

Jaipreet Lully speaks with Cambridge film societies on the political potential of film and TV

Film and TV can move us in ways that other arts cannot. When I first watched Shane Meadows’ This is England (2010), I was shocked and disturbed by the raw depiction of racist violence and extremism amongst the youth of Thatcher’s Britain. Watching the neo-nationalist Combo (played by Stephen Graham) explosively beat and maim Milky, the only mixed-race member of the group, has been seared into my memory. It shows us how easily lost and wayward identities can become consumed by hateful, white supremacist ideologies.

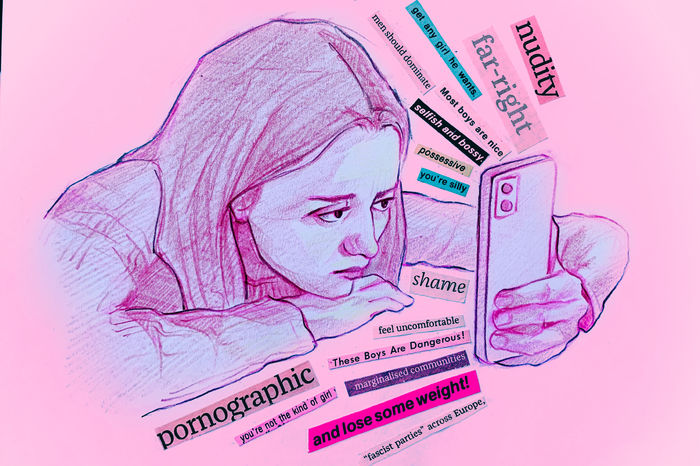

Having studied Film in secondary school, I was intrigued by the appearance of This is England on the curriculum — I wondered how reception of the film differed when studied in a classroom environment. This has been a particularly important part of the debate sparked by Adolescence (2025), a limited series exploring the corrupting dangers of social media and the ‘Manosphere’ on young boys. In fact, on Wednesday 19th March, Anneliese Midgley, the Labour MP for Knowsley, powerfully called on Prime Minister Keir Starmer to screen Adolescence in schools and Parliament, which has been progressing over the past few weeks.

So, what is the place of film and TV in political and educational debate? James, President of Cambridge University Film Association, about the place of films and TV shows in political and educational debate, tells me they “can absolutely be useful in debate.” He continues, “I think Adolescence is really interesting and I think adults would probably benefit the most from watching it, because the world of the victim and perpetrator is the one kids live in, it’s not massively new or educational to them, although it is of course taken to the extreme consequences.”

“Perhaps we should embrace the emotion – perhaps that emotional response is what the world needs to talk about these issues”

I wondered whether the government’s move encouraging schools to screen the series would make any substantial difference to the growing polarisation between young boys and girls. After all, Adolescence, although based on real-world behaviours, is still a fictional story. The feelings of visceral dread and worry felt by parents watching Jamie’s actions unravel are most likely not reciprocated amongst school children, at least not so intensely.

Gina, an MPhil student studying Film and Screen studies points out that “the viewer could fail to make the connection between that specific story and any wider societal issues. Take Adolescence: I’m sure more than one person has come out watching that and thought ‘what a tragic tale’, thinking it could never happen to them.”

Film and TV often requires an active, introspective reflection from viewers after watching, which might not come naturally to children who watch shows like Adolescence as part of a mandatory curriculum. But having said that, we mustn’t underestimate the powerful influence of emotive, entertaining stories on our subconscious, which education in schools perhaps does not possess. Gina tells me: “Shows like Adolescence are designed to elicit an emotional response that must not cloud our rationality. Yet perhaps we should embrace the emotion — perhaps that emotional response is what the world needs to talk about these issues.”

Film and TV sparks an empathy in us; an understanding of behaviour and ideology which is depicted in front of our eyes. Schoolchildren might not be thoughtfully pondering the moral messaging of Adolescence with their peers, but they may still feel something at the time of watching, whether it’s sadness for his family or empathy for Jamie’s lost self.

Fergus, a committee member of Cambridge World Cinema Society, tells me that they screen films to “inform, to inquire, to push, and to thrill!” Film and TV may not provide a solution to unlearning harmful ideologies like misogyny and racism, but they are certainly useful tools through providing the seed which could grow into more meaningful, bigger conversation. Talking about the power of film, Fergus tells me, “at its best, there’s no better, more involving collective experience. At the same time, cinema is only one tool in the inventory of progressive activists.”

“Anneliese Midgley, the Labour MP for Knowsley, powerfully called on Prime Minister Keir Starmer to screen Adolescence in schools and Parliament”

James tells me about his experience watching the film How to Have Sex, a moving drama covering issues of sexual consent and peer pressure through a holiday with a group of young girls. “I didn’t know anything about it going into it and thought it was like the Inbetweeners movie but gender flipped. It’s quite the opposite, and as a guy who went to an all-boys school, seeing a very down-to-earth female coming-of-age experience was really interesting and ultimately very sad.” He continues, asserting that “I think it’s an important film for young men to see in particular, especially in Britain where the drinking culture the film addresses is so prevalent.” Film can both provide us with a perspective which we can relate to, but also with one we haven’t seen before.

What I find special about film and TV is not only its educative, mind-opening power, but also its accessibility and adaptability as a cultural artefact in our lives. I wanted to explore how the type of film and TV watched by Cambridge students differs at university to at home. Gina tells me that, with the intensity of university, “in my downtime, I always return to something easy on the mind, like a sitcom or romcom.” But, for her “returning home usually gives me the headspace to step outside of my comfort zone of my own accord.”

In contrast, James reveals he is “a lot more deliberate” in his choice of film at university, whereas at home, he watches “whatever my family has on, so Bake Off or First Dates feature a lot more.” Although I’ve made a case for its importance as a political tool, film and TV is also a source of escapism or comfort. It can be enjoyed no matter our stage in life, our location, or our frame of mind — it is an enriching, eye-opening experience, whether consumed within the context of political debate or not.

Want to share your thoughts on this article? Send us a letter to letters@varsity.co.uk or by using this form

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026