‘This is Going to Hurt’: an honest insight into the NHS

Madeleine McLure urges you to watch this eye-opening portrayal of life as a doctor, complete with morbid bodies, personal pain and moments of humour

I first began watching BBC One’s new drama This is Going to Hurt (based on Adam Kay’s sell-out book and live show of the same name) while eating my dinner. Big mistake. I’m not generally squeamish, but I’m still an MMLer and the thought, let alone the sight, of a prolapsed umbilical cord tends to be enough to put me off my tortellini and pesto.

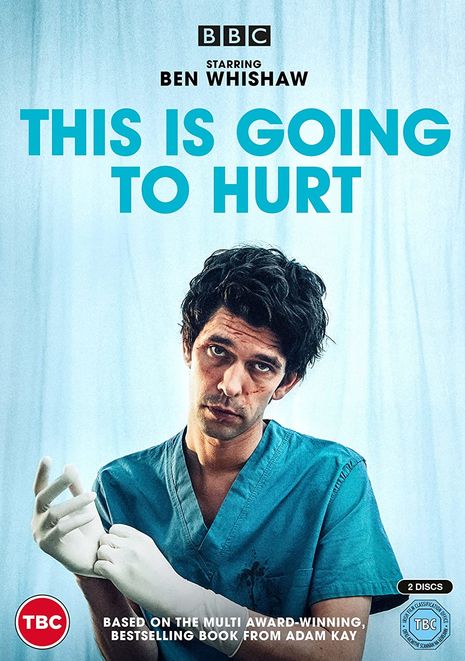

This wasn’t the only reason I didn’t make it to the end of episode one in one go. The series is gripping, tense and claustrophobic, but also pretty distressing. The hospital is a hostile space, not just for patients, but for healthcare workers of all description. It follows Adam (Ben Whishaw), a junior registrar on rotation on the obstetrics and gynaecology ward (‘brats and twats’), attempting to negotiate an impossible waiting list, staff shortages, personal conundrums, pressure from management, racist patients, and so on. I first found him arrogant, but this veneer of confidence quickly shatters, giving way to a complex character who struggles under the weight of the expectations he and others have of him.

It’s not as though there is a redeeming sense of camaraderie between the colleagues in the face of the immensity of their responsibility. In dangerously short supply, those present are portrayed as being at war on all fronts, including with one another. The ‘team’ seem intent on maintaining a culture of hostility, where one is only permitted to communicate through the medium of sarcasm (which I’ve heard is the lowest form of wit).

“Exhaustion seeps out of the doctors”

Reflecting on the title, I asked myself: this is going to hurt for whom? For fellow doctors? Medical students? Us at home? If it bears any resemblance to reality, I think the answer, probably, is for the patients. I struggled most with the weariness with which they were treated, not because the doctors don’t care, but because they don’t have the bandwidth to worry about everyone: under these conditions, the hospital becomes a realm of treatment, exclusively.

The NHS is shown to be on its knees: exhaustion seeps out of the doctors, increasing in acuteness the more junior they are. The series opens with an image of Adam asleep at the wheel of his car, having not made it beyond strapping himself in the night before. This made me think of my mum, who, as a junior doctor, after a tough shift, also fell asleep at the wheel — while the car was still moving. Her head injury in the 90s evidences the unsustainability of this kind of pace, yet Kay’s book (set in 2006) would suggest little has changed.

The crisis must be at least ten times more severe following the pandemic. An image of a consultant relaxing in the evening with a nice book did not correspond to my experience growing up with one such consultant, but a ‘hierarchy of tiredness’ is clearly in operation as junior doctors grapple with an untenable workload, constant examination, and little experience of how to deal with the very real ‘life or death’ scenarios to which their pager summons them.

The physical and mental decline of Shruti (Ambika Mod), Adam’s SHO, over the course of the series viscerally attests to the life-threatening situation this mental and physical toll engenders — not just for the healthcare workers themselves, but for patients, upon whose bodies the fallout of no sleep, food or chance to go to the toilet for 12 hours is ultimately wrought.

“The doom and gloom lifts occasionally, allowing glimpses of humour”

The show captures how patients wrongfully become background noise, an inconvenience until something goes wrong (and something goes badly wrong). The enormous effect of a traumatic incident for Adam is shown through intense flashbacks and intrusive thoughts, which plague life both in and out of work. This mistake not only nearly costs him his career, but damages several relationships, including with his boyfriend-fiancé (one ‘e’, as Adam points out) and colleagues, following an anonymous complaint to the GMC (the dark overlords of the medical profession). Fear of being ‘struck off’ leads doctors to make poor decisions poorer, as they attempt to cover up the truth to the detriment of patient safety and outcomes.

The doom and gloom lift occasionally, allowing glimpses of humour and levity into difficult situations. Adam frequently breaks the fourth wall, providing useful context for medical lingo and decisions or simply to critique a particularly unusual choice of baby name. The luxury of the private sector (asparagus risotto — in July!) is shown to be an illusion as the NHS must sweep in to deal with situations for which they are inadequately prepared. This is Going to Hurt also touches on important themes which stretch beyond the purely medical, including racism, domestic abuse, suicide, body image, class tensions and testimonial injustice. Blood, guts, bodily fluids, and then ‘warts and all’ would be the aptest description of the way Kay depicts his experience of being a doctor.

Anyone who plans on accessing NHS treatment, or straying anywhere near a hospital, needs to give the drama a go. Although it may hurt — and it should hurt — it is important that we, as tax-paying or future tax-paying or future tax-hopefully-paying, individuals attempt to comprehend the magnitude of the pressure placed on the heroes for whom we stood on our doorsteps and clapped. Just maybe leave the tortellini till after. After all, if the medics can wait, so can you.

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Gov grants £36m to Cambridge supercomputer17 February 2026

News / Gov grants £36m to Cambridge supercomputer17 February 2026