Autistic Characters in Film and TV: Authentic, or Archetypal?

Anna Trowby takes a close look at how autistic characters have been portrayed in Film and TV.

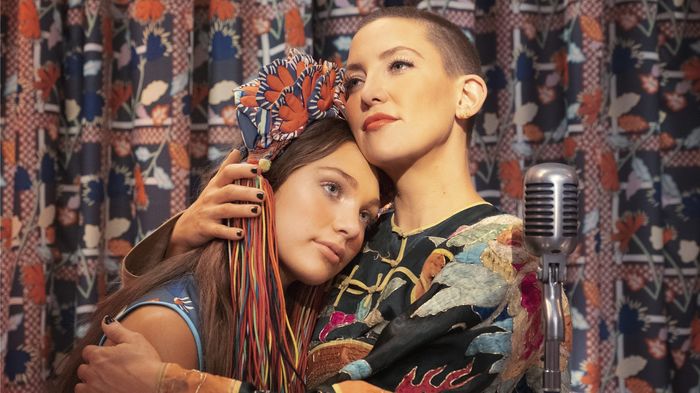

The film and TV industry is not exactly well-renowned for its onscreen or behind-the-scenes talent. Sia’s recent film, Music, was met with critical and commercial backlash for its shallow portrayal of its autistic protagonist. The controversy surrounding the film prompted me to reflect on the history of autistic characters on screen, who are rarely portrayed in a humanised way.

“Despite this paucity of representation, I, and a lot of other autistic people still manage to relate to characters who are not necessarily autistic.”

Filmmakers like Sia often make the mistake of seeing autistic characters as a clump of traits associated with their conditions as opposed to individuals with their own personalities and interests. I have autism, and it has shaped my life in many ways, but I also do not see it as the defining and singular aspect of my life. It is therefore frustrating to see TV shows and films treat autistic people in ways which rob us of our core humanity, by depicting us as reducible to our autism.

Although representation and inclusion have improved in recent years, TV and filmmakers still struggle to portray autistic individuals in a dignified manner. Accurate depictions of autistic individuals are incredibly rare to find in this medium, let alone autistic characters. Despite this paucity of representation for myself, I, and a lot of other autistic people still manage to relate to characters who are not necessarily autistic, but have behaviours associated with the condition.

A lack of representation has meant that autistic individuals like me have looked elsewhere for people to identify with. It would of course have been better if there were better media portrayals of autistic people, but regardless, I and many others have come to identify strongly with characters who have made me feel more comfortable in my skin, even if they were not created with the intention of appealing to the traits of autistic people.

It’s worth initially looking at characters who are explicitly shown to be or portrayed as autistic onscreen, although these depictions mostly conform to the ‘autistic savant trope’. As much as I enjoy Rain Man and Dustin Hoffman’s touching performance, it is not necessarily realistic of all autistic people’s experiences. Although the film promoted widespread understanding about the condition, it also perpetuated tired stereotypes regarding autistic people — that we are all misunderstood geniuses and we have an innate understanding of numbers. This stereotype can also be found in the character of Sheldon Cooper from The Big Bang Theory, as well as Dr Shaun Murphy from The Good Doctor.

Only 10% of people with Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD) fall into the autistic savant category that features predominantly in film and TV’s depiction of these characters, and while these portrayals may ring true for them, it does not reflect the wide range of people with autism, many of whom are incredibly sociable and do not necessarily excel in academia. The ‘autistic savant’ is also often the subject of ridicule, being used as a prop in the comic narrative rather than the comic initiator themselves, which reinforces the idea that autistic people cannot be considered humorous outside of their autism as well as implying that autistic people exist to be made fun of rather than respected.

As for more positive portrayals of autism, these are not always to be found with characters explicitly shown to be autistic. When I delved deeper into characters that I have strongly identified with onscreen, I realised that many of these depictions rarely classify their characters as autistic. Take Tina Belcher from Bob’s Burgers; Tina has certain behaviors that are strongly associated with autism, such as a difficulty communicating her emotions, strong fixations on particular things and panic attacks. But Tina is also more than these traits — her character resonates with me because of her multifaceted personality and interests, and she is also shown to have a wide group of friends, something rarely seen for autistic people onscreen. However, Tina is never explicitly shown or said to have autism.

The attachment of autistic viewers to characters who are not diagnosed with autism themselves is fairly commonplace. Spock from the Star Trek franchise is known for resonating with autistic viewers like me because of his difficulty expressing emotions and reading the feelings of others. Even though he is never shown to have autism, Spock’s struggle to articulate himself and maintain relationships connects to autistic people who struggle with these issues daily.

I also have to give credit to Danny Pudi’s excellent work as Abed in Community, a series I have started watching recently. Abed is one of a few autistic characters of colour portrayed on screen, and he is also one of the few that are depicted as individuals rather than the sum of their condition. What I love about Abed’s character is how much he departs from tropes associated with autistic people. While he is shown to struggle with expressing his emotions and understanding others (often resorting to film references to navigate social situations), he is also shown to be one of the more socially astute characters in the show, with a strong interest in film and a wide circle of friends.

The same things can be said of Maurice’s character in The IT Crowd, although again, the character is not explicitly shown to have autism. Even though I’m wary of autism being played up as a comic device, I enjoy Richard Ayoade’s performance and I strongly identify with Maurice’s nerdiness and awkwardness. I suppose this could be seen on my part as being a ‘problematic fave’, but I don’t feel that the show dehumanises Maurice for comic effect in the way that Sheldon is in the Big Bang Theory.

There are dignifying portrayals of autistic people on screen that try to convey the humanity of these characters. Saga Noren from The Bridge provides a fulfilled and complex female perspective on autism, while Abed’s depiction is partially informed by creator Dan Harmon’s experience with autism. However, these examples of autistic viewers finding kinship with characters who were not necessarily created with the intention of being autistic show not only how necessary it is to create characters who are authentically autistic on screen, but also how we can find unity with non-autistic characters regardless.

As much as I identify with non-autistic characters, there is still value in seeing yourself represented accurately, especially with regards to something that can be as isolating and misunderstood as autism.

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025

News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025 Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026

Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026