Koyaanisqatsi, or a tale of destruction

Vulture Editor Isabel Sebode muses on the unsettling beauty of the experimental documentary Koyaanisqatsi and the currents of its social commentary

Koyaanisqatsi (noun): “Life out of balance”; “Life of moral corruption” (Hopi)

Hypnotising music envelops us as we enter into the world of Koyaanisqatsi — a world in which moral corruption and imbalance conduct their tyrannical reign. Godfrey Reggio’s 1982 experimental documentary is no common project, but rather a delicately ambitious exploration of modern life. From nature to industry, the film meanders through modern history and illustrates its estrangement from humankind’s origins. The first of a three-part series (including Powaqqatsi (1988) and Naqoyqatsi (2002)), this film-collage reinterprets the documentary genre. Instead of familiarising ourselves with the unknown, we watch through a focused lens which slowly paints the everyday as revoltingly absurd.

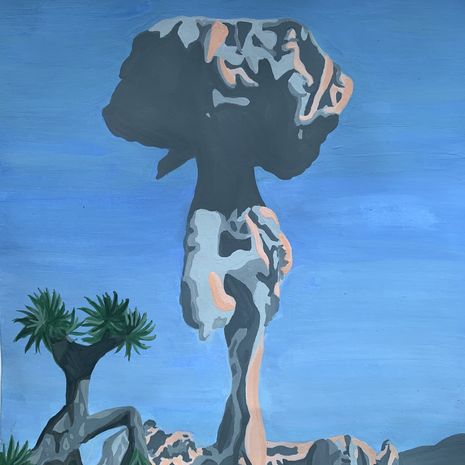

The first sequence of the film confronts us with the most radical juxtaposition. From cave paintings to the explosion of Apollo 11 (our vector to the moon), we witness the static stone being overtaken by the momentum of modern life. “Aim for the stars”, the movie could seem to say, yet the subsequent images advocate the antithesis. Only fleeting glimpses of nature fill the screen before man’s intervention expresses itself through power lines and mining trucks. The detonation of an atomic bomb next to a Joshua tree jarringly terminates this sequence, irrevocably fusing nature with human destruction. Both seem equally natural in the desert environment, the explosion sickeningly majestic.

Urban life begins dominating the montage as buildings are built and demolished, while humans hurry from one place to another. Consumption of food, entertainment and commodities constitute the central point of the narrative, before close-ups of microchips remind us of the network of streets and buildings we gazed on earlier. The narrative is circular as it concludes with another rocket launch. Its trail of smoke and debris pollutes the air whilst we shift back to the rock art metonymic for an era of life not yet corrupted.

“We feel like voyeurs, invading a different world only to realise that this is our own.”

The music comprising the aural tissue of the cinematic collage is composed by Philip Glass and includes deep male vocals rhythmically chanting “Koyaanisqatsi”. This mantra supersedes the various cinematic elements, manifesting the notion that life truly is out of balance. Like our social reality, the music is deafening. “The Grid”, backdrop to the fast-paced scenes of human transport and digital entertainment, evokes the structured absurdity of Alice’s Wonderland, only here there are no wonders to discover. Instead, crowds of humans migrate in a single direction with Microdata, KFC, and Sony looming over them as they go to fulfil their roles in the tragic farce of our society. As people discover the camera, we feel like voyeurs, invading a different world only to realise that this is our own.

In this world, even the most natural aspects of humanity are rendered artificial. A deep sense of repulsion fills me as I can only stare at humans mindlessly existing in the advertisement-plagued city. Fast food courts are the stage for the fetishisation of mass-produced items, captured by the invasive cinematic lens. We witness the automatised production of jam-filled pastries, sausages and Twinkies — the gluttony almost reeks from the sanitised production lines. Coca-Cola and burgers provide the fuel for modern-day society, which functions through artificiality only to work and produce more.

Reggio does not allow us to engage in mindless consumption. He subverts the documentary genre as no information is being fed to the complacent viewer, who instead needs to mentally labour for a meaning. Koyaanisqatsi forces us to slow down. After the claustrophobic experience of the awfully populated streets, the concluding rocket launch offers a moment to catch one’s breath in-between the mania. Even this sensation proves to be anxiety-inducing, as rather than searching for solace in nature, we have found our source of stability in technology. The beauty of the rocket fire is as grounding as the shots of the landscape, as familiar to the eye.

I suppose I experienced the movie slightly differently. In my naivety, I trusted the humble YouTube link and watched the movie in reverse. For me, the robots disassembled. The cups filled themselves. Society moved backwards, away from where it was so resolutely going. Urban scenes receded, eventually leading us back into the desert landscape. Yet, Reggio did not intend to grant this escape. We should be uncomfortably confronted with existential questions that force us to answer for ourselves: How did we get here and why do we accept this as our normality? We breathe deeply as we glide over the mountainous landscape and suffocate in the images of city life. Nonetheless, we accept the latter state. Reggio reminds us that this is not normal, for with every impulse of apathy towards this loss of nature, our life becomes increasingly fragile.

“Koyaanisqatsi is a theatre of capitalist innovation or, more specifically, its tragedy.”

Now, what is at the core of Koyaanisqatsi? Perhaps a guided meditation leading us to discover why our life is unstable and corrupted. Perhaps a depiction of the danger of innovation and its culmination in destruction. Perhaps the goal of estrangement, by which the grinding of machines reveals the threat penetrating into our social structure. Either way, Koyaanisqatsi is a theatre of capitalist innovation or, more specifically, its tragedy.

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 Fashion / The art of the formal outfit 18 December 2025

Fashion / The art of the formal outfit 18 December 2025 Lifestyle / Summer lovin’ had me so… lonely?18 December 2025

Lifestyle / Summer lovin’ had me so… lonely?18 December 2025