Normal People: A tender adaptation of a beautiful novel

Normal People hums with the success of a literary adaptation done right, writes Nicholas Harris.

Generally, literary adaptations go one of two ways. There is the more conventional approach which I associate with BBC adaptations of Dickens novels: the story is serviceably told by competent actors who squeeze the utmost out of a novel, but inevitably give us a thin impression of the original. The alternative (cf. Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange and David Cronenberg’s Crash) sees the director and the writer as pares, duelling over the same thematic territory to create something which is the synergy of colluding, sometimes conflicting, creative energies. More often than not, the resulting adaptation sits alongside or even towers over the novel, telling us more about the director than the book it is based on.

Rather than diluting its content or wrenching it onto new ground, BBC Three’s Normal People is a frictionless channelling of its source material. It would almost feel worthwhile to read the novel in tandem with this adaptation, such is their similarity. This no doubt owes partially to Sally Rooney, who serves as its executive producer and co-writer. Many critics have noted Rooney’s terse and economical style, and it is well rendered here through unobtrusive direction from Lenny Abrahamson and Hettie Macdonald and the bravura performances of Daisy Edgar-Jones (Marianne) and Paul Mescal (Connell).

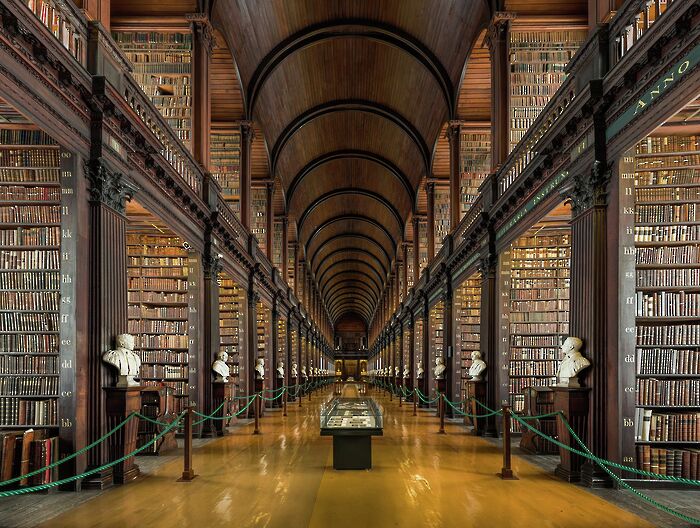

The novel’s tenderness relied upon a frank communication of complex emotions, made possible here by the leads’ ability to move among and between overconfidence, fragility, anguish and passion. Just as the novel was told in short, Austen-esque chapters, each half hour episode lands as a weighted crotchet, filled with resonance that pulls you forward. The story is simple; it follows the lives of Connell and Marianne, an on-off couple, from their sixth form in rural Ireland through to their lives at Ireland’s premier university, Trinity College Dublin. The plot’s axis is the shift in social hierarchy between school and university. At school, Connell was the popular sportsman and Marianne a reading-a-book-at-break loner, but they find their positions swivelled in their new academic surroundings.

“The novel’s tenderness stemmed from a frank communication of complex emotions.”

What follows are three years of misunderstandings and miscalculations for the pair. Deeply in love, both characters inflict their flaws upon the other while remaining their buoy through larger storms. Separated, they fall into the disharmony of their personal grooves. Connell tends to plunge into self-doubt and struggles to find his confidence while Marianne’s strident belief in her own unlovability leaves her exposed to cruel abuse at the hands of a series of coercive boyfriends. Though it should be noted that the latter serves as testament to the high availability of men to perform this role, both novel and series expose the capacity for destructive selfishness in male adolescents.

The Connell-Marianne narrative was only ever one part of the novel’s appeal, and the deeply contemporary nature of their university surroundings reverberates on screen as it did in the page. The wardrobe is straight out of the Sidgwick catalogue and I warn every Cambridge student to be prepared to wince at a series of bloviating seminars – just ‘how many examples of the picaresque novel are there which centre a woman so boldly and without condemning her?’ Some moments verge on pastiche, such as the already-passé discussions about free speech on campus: ‘…he’s not a Nazi…but by that reasoning, you’d have to invite everyone everywhere to debate everything…’ But Marianne and Connell’s struggles regarding mental health, the pretensions of their classmates and the deracination of attending a cosmopolitan university from a provincial background are handled with a seasoned intelligence.

Sally Rooney’s novels have a perfect ear for the trials and tribulations of student life, but they can be deaf to its more ludic side – a lacuna replicated here. The closest her screenplay and her characters get to humour, or even fun, is often little more than a well-honed ironic wryness – all the better to protect their brittle interior worlds. The apparent joy of undergraduate friendships is exposed as empty falsehoods. For, in Rooney’s world, we don’t really know anyone beyond our most intimate confidants. There are few laughs to be had here, except in response to those equivocal moments where you recognise yourself on screen.

The two leads are also rather less plain than the every-couple you had in your mind’s eye, as evidenced by the already considerable fandom around Paul Mescal. This might be alienating, but such is the maturity of their performances that it would be churlish to detract from the humming chemistry they achieve together. And given that this is surely one of the last new dramas for a while, it would be equally churlish not to be grateful for an adaptation as honest and poignant as this one.

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025 News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025

News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 Science / Did your ex trip on King’s Parade? The science behind the ‘ick’12 December 2025

Science / Did your ex trip on King’s Parade? The science behind the ‘ick’12 December 2025 News / Pembroke to convert listed office building into accom9 December 2025

News / Pembroke to convert listed office building into accom9 December 2025