The film that helped me deal with imposter syndrome

Andrei Rublev reminds Alex Harrison that none of us really know what we’re doing all the time

As for most students, my first year at Cambridge was a stressful time. I experienced both the shock of a new territory, and the lurking suspicion that I think most of us share, that you’re not, on some level, meant to be here.

These circumstances, awkward as they were, led to something rather pleasant: a rediscovery and fuller appreciation of Andrei Tarkovsky’s renowned film Andrei Rublev. It’s a film I’ve found great comfort in. The first time I watched it, about a year before, I had written off Rublev as ponderous, overwrought, and occasionally self-indulgent.

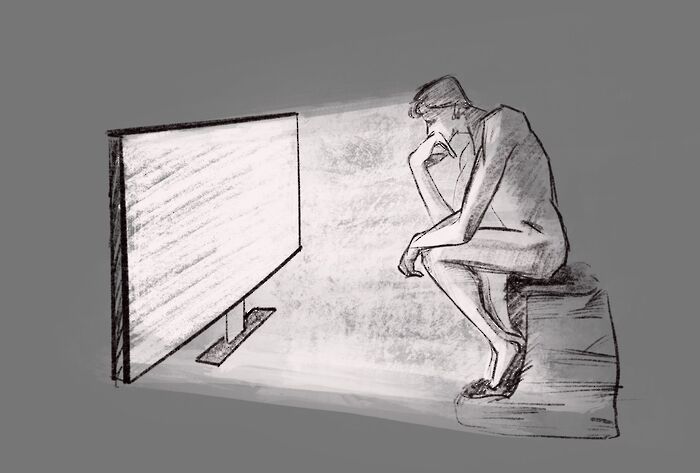

Re-watching it at a film society screening, I found something unexpected in it: an ultimately hopeful meditation on impostor syndrome.

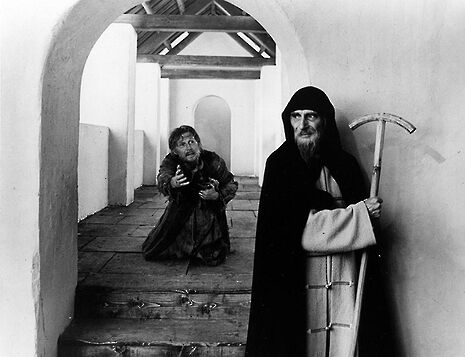

The icon painter Andrei Rublev travels through 15th century Russia, discussing his artistic and personal travails with a motley group. Warring princes and invading Tatars prevent him from fulfilling his artistic calling, until witnessing a young boy building a church-bell without any training gives him the hope to continue. It is the final chapter of the film that on both viewings stuck with me. Rublev has effectively given up: his works until that point are destroyed by war, his companions are scattered, and he has taken a vow of silence.

Although he has external problems which are directly to blame for his condition, his story up until that point is a deeply insecure one. Throughout, his discussions are about the art he is going to produce, the churches he is going to paint. Yet, in an agonising sequence, we see the shock that is produced in him when presented with a set of white walls and told to get on with it.

Tarkovsky’s optimism and hope set him apart

We spend very little time seeing the famous figure at work, and we genuinely don’t know whether he will succeed. He speaks with other great artists, trying his hardest to see himself as their equal, and yet throughout, one is left with the lingering sense that he doesn’t truly believe himself. And so, why does bell sequence save him? He sees a boy, many decades his junior, succeeding seemingly by chance while he has struggled his entire life, and yet this spurs him on?

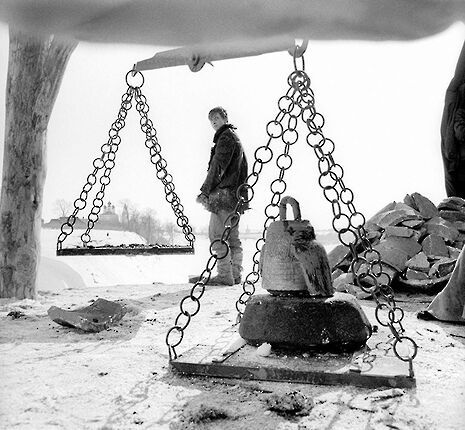

I would argue that it is in this sequence that Rublev fully gains a self-awareness, in recognising himself as the same as the boy. Throughout the bell-making, the child laments that he doesn’t really know what he is doing, and yet has volunteered to do a duty where great things are expected of him.

The fact that he is ultimately successful is irrelevant. Rublev realises that grinding away for years on end without satisfaction, or seemingly getting away with a blind stroke of luck, can ultimately produce the same feeling, which they are then both able to overcome. Andrei utters the line “You’ll cast bells. I’ll paint icons.”, and for the remaining few minutes of the film all we are shown are the paintings he produced after this incident, safe in museums and churches, in an epilogue as cathartic as Barry Lyndon’s ‘They are all equal now’.

In conversation with an academic at Cambridge on Tarkovsky, I was told a story I have unfortunately not been able to verify. Supposedly, in Soviet cinemas it was common for audience members to leave notes to the director commenting their views, one of which stated, “In watching your films, I no longer feel alone”. It might be considered ironic that an undoubtedly egocentric director, who was routinely criticised for making films perceived as overly individualistic and anti-communitarian, got this response. In my view, however, that was the mark of his supreme talent.

In only ever meaningfully writing about himself or a near-proxy, he was somehow able to make the personal seem universal. If one is willing to engage in a small amount of intellectual cherry-picking, there is a great comfort to be found in his films in times of stress.

In my mind, it is Tarkovsky’s optimism and hope that sets him apart from both his influences and his imitators, as even at his downbeat moments, there is an opportunity for transcendence.

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026 News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026

News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026 News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026

News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026 News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026

News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026 News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026

News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026