Agnès Varda: The Woman Who Invented Cinema

Film and TV editor Madeleine Pulman-Jones remembers iconic French filmmaker Agnès Varda in light of her death at 90

“I didn’t want to be a woman who makes films. I wanted to invent cinema.”

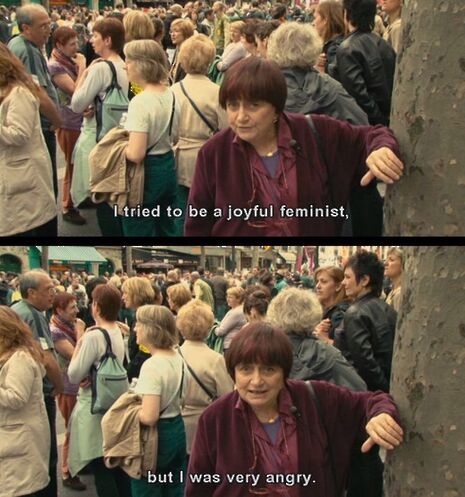

The news of Agnès Varda’s death rained down on me this morning in showers of news headlines and messages from friends. The messages came mostly from women my age for whom Varda had acted as a kind of cinematic fairy godmother – friends who had watched Cléo de 5 à 7 in the first year of their French degrees, friends with whom I had sat around coffee shops for hours talking about Varda’s Vagabond, about her joyful feminism, about her carefully painted halo of burgundy hair. With her debut feature La Pointe Courte in 1954, Agnes Varda opened a window and let the sunshine in on generations of cinema-goers. Varda left the superfluous and the cynical in the shade, illuminating only the strongest of images, her sincerest impressions. She didn’t shy away from the underbelly of humanity but shone a light on it, and somehow under her hopeful gaze even the darkest moments seemed to emanate a kind of light. Even the news headlines seemed almost like messages from friends. United by collective grief, Varda fans the world over didn’t even seem to be trying to be coherent, content to sit by the proverbial window, bathing in the last hours of Varda’s sunlight. On the 29th March, Cambridge was aglow with such Varda-esque sunshine, but I felt cold and damp, as though I was being followed like Eeyore by a personal raincloud.

“Fairy godmother” is a far more accurate term of endearment for Varda than “grandmother of the Nouvelle Vague,” a title she begrudgingly wore for years, despite being a mere two years older than Jean-Luc Godard, the filmmaker often considered the movement’s poster-boy. But even as I write the words “fairy godmother” I cringe a little. I chose those words to avoid implicating myself in this ongoing “grandmother-ification” of one of cinema’s most youthful characters, but feel that, in spite of myself, I may have fallen into its trap. Separately from her reputation as the “grandmother of the Nouvelle Vague,” over the past couple of years, due in part to the publicity around Faces Places which she made in 2018 with artist JR, Agnès Varda has become the internet’s favourite celebrity grandmother. She has been memed endlessly, and even prestigious magazines have placed her on their covers sitting in her garden, cat on her lap, looking like the bohemian grandmother you never had. There’s nothing inherently wrong with this affectionate caricaturing – Varda herself to some degree seemed to delight in her role as a kind doyenne of eccentrics – but it hints at a kind of sexist patronisation that no male contemporary of hers has had to endure. It is saddening that in 2019 when I sat down to write about Varda, one of the things I felt I had to prove was that “Agnès Varda is more than a meme.”

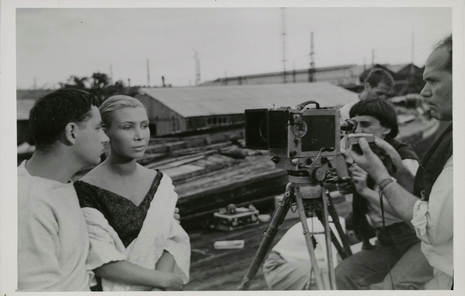

Having begun working as a photographer after studying at the Sorbonne and the École du Louvre, Agnès Varda’s began a career in cinema that has spanned over half a century and encompassed numerous forms. Perhaps her most famous film, Cléo de 5 à 7 (1962), was revolutionary in its exploration of female lived experience through cinematic real-time (the film’s hour-and-a-half capture two hours in the life of its protagonist), setting the pace for a distinctly feminist cinematic practice which Varda was to continue for the remainder of her career. After the Nouvelle Vague supposedly came to a close in 1967, there were her mid-career experiments with the musical (L’une chante, l’autre pas [One Sings the Other Doesn’t], 1977) and political documentary (Black Panthers, 1968), and her later development of the film-essay in works such as Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse (The Gleaners and I, 2000) and Les plages d’Agnès (The Beaches of Agnès, 2008). Varda began more and more to make herself the subject of her own work, whether by putting herself into her own films as in Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse or Les plages d’Agnès, or by making installation pieces of which she was the unspoken but definite protagonist. Her essayistic style, reminiscent of French auto-fiction, predates the recent trend for memoir in both cinema and literature. Varda’s genius for self-reflection and her talent for finding poetry in apparent mundanity, form the foundations of an oeuvre distinctive in its individualism, and democratic in its legibility.

Agnès Varda had a rare way of making you feel as though the way you look at things must be as beautiful as the way she looked at things. Ways of looking abound in Varda’s films – she loves mirrors and windows, keyholes and shifting focus. A friend of mine said to me this morning that Varda’s death feels like “the end of the greatest era of cinema,” but it’s up to us to see to it that Varda and her era do not truly die. We need to preserve Varda’s films and those of her contemporaries – we need to restore films by women filmmakers whose work has been cast aside. Despite my personal ambivalence about Varda’s recent internet fame, it can only be positive that my generation has come of age with at least some form of awareness of such an inspiring woman filmmaker. Varda set out to “invent cinema,” but what she achieved was something in a way more powerful – she invented her own cinema

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025 News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Comment / League tables do more harm than good26 December 2025

Comment / League tables do more harm than good26 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025