Nothing happens and everything happens: the cinema of Chantal Akerman

In her second column, Madeleine Pulman-Jones considers the filmography of Belgian director Chantal Akerman

“[The star system makes] idols. I’m fighting against idolatry. That’s one of my main concerns. That’s why the way I shoot is like that [gestures straight on] so it’s a one to one relation with the audience ... people are not free when they have idols.”

Chantal Akerman’s distaste for idolatry, expressed in a recent interview, is perhaps as much about identity as it is about idolisation. Akerman was a filmmaker who fought hard for her right to remain just that. People found Akerman more digestible when they pigeonholed her as a woman filmmaker, a Jewish filmmaker, a feminist filmmaker, a queer filmmaker. Born in 1950 in Brussels to two Polish concentration camp survivors, at the age of 15 she saw Godard’s Pierrot le fou (1965) and, realising that film could be “like a novel,” she decided that she no longer wanted to be a writer but a filmmaker. Akerman’s rebellious personality informed her cinematic education as much as it did her later cinematic practice.

“The stillness of Akerman’s camerawork and her actors is such that even a change of shot feels kinetic”

After dropping out of school at 16 to study at ISNAS, the Belgian film school, she then dropped out of film school, finding the educational setting too restrictive and was frustrated at the lack of practical filmmaking. She funded some of her earliest films by unconventional methods, such as stealing money from the porn cinema where she worked in New York and trading diamond shares on the Antwerp stock exchange. By contrast, Akerman’s aesthetic rebellion appears to be relatively subtle. Fascinated by the use of time in portraying lived experiences, very little ‘happens’ in Akerman’s films – instead she prioritises the lengthy documentation of daily rituals and moments of reflection, often briefly interrupted by unexpected moments of sex or violence.

Akerman’s films resist form as much as she herself resisted being boxed. Watching Akerman’s 1975 masterpiece Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai Du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles feels something like skipping a button over and over again while trying to put on your coat, for 201 minutes. Jeanne Dielman refuses to conform to the cinematic conventions of depicting the passage of time, affording a woman’s quotidian domestic life the temporal scale of a Hollywood epic. From the “plot” alone, the film appears decidedly conventional.

A post-war Belgian widow resorting to sex work to feed her teenage son sounds like a slightly more controversial version of Mildred Peirce (1945, dir. Michael Curtiz), but Akerman’s execution of this plot is outlandishly elusive. With no sound-track, barely any plot and the use of only static shots, Akerman tells the story of three days in Jeanne Dielman’s (Delphine Seyreig) life. The organisation of her schedule is immaculate. Her male customers are received with the same absent-minded pragmatism as that with which she turns off a pot of soup, that is, until a pot of overcooked potatoes throws her schedule and life into turmoil.

What we don’t know about Jeanne Dielman is more important than what we know about her. Jeanne Dielman is quite possibly the first domestic epic, and if Jeanne’s consciousness is the landscape of our epic, then the more virgin land and uninhabited territory, the more exciting for us. A kind of radical mundanity pervades the film, to the extent that even the most menial tasks take on an existential significance – as a sack of potatoes is peeled in real time, the prospect that she might slip and cut her finger becomes unbearably suspenseful. Just as Jeanne is unable to avoid life’s inevitable chaos, attempts to dismantle the puzzle of the film are futile. When Jeanne takes out the jumper she is knitting for her son after dinner and only knits one or two stitches each night, we perhaps notice just how little Akerman chooses to give away.

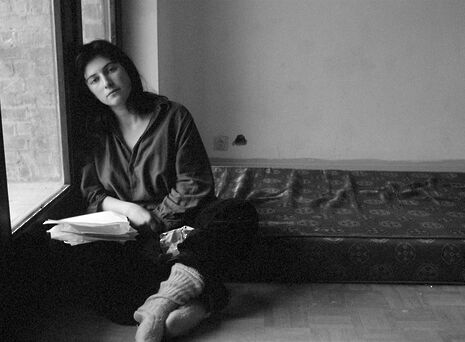

Though it is tempting to prioritise the discussion of Jeanne Dielman in discourse surrounding Akerman’s filmography, its existence is unimaginable without Je, tu, il, elle (1974). In the first half of Je, tu, il, elle, Chantal Akerman’s fiction feature debut, Julie, played by Akerman herself, has for some unknown reason locked herself in a sparsely furnished room with nothing but a pad of paper and a bag of sugar. She spends weeks in the room re-writing a letter to an unspecified person over and over again, and subsisting off spoonful after spoonful of sugar.

Midway through the film, she leaves the room and hitchhikes to the city. After an ambiguous sexual encounter with the lorry driver giving her a lift, she arrives at the house of a woman we assume is her ex-girlfriend. She makes Julie Nutella sandwiches, and though Julie agrees to leave in the morning, they have sex. When in her room Julie declares in voice-over, “I am going to play with my breathing,” Akerman too is playing with cinematic respiration.

As in Jeanne Dielman, the stillness of Akerman’s camerawork and her actors is such that even a change of shot feels kinetic. It is significant, then, that the sex scene is filmed starkly with few cuts and no camera movement. Even in moments of extreme intimacy, Akerman’s objective perspective is unwavering. Akerman stated that her static cinematography meant that the audience “always knows where I am.”

It feels reductive to leave a discussion of Akerman’s work at Jeanne Dielman and Je, tu, il, elle, without even touching on her documentary work. It too is reductive to neglect to view Akerman’s films through the lens of feminist theory. However, in an overview of her work, it feels only right to give justice first and foremost to her prowess and artistry as a filmmaker rather than to the films’ political and social contexts, however inherently political they may be.

Having tragically committed suicide in 2015, Chantal Akerman’s star previously only shone in the firmament of avant garde and feminist cinema. Thanks to the gradual movement towards an inclusive cinematic canon Akerman is now finally on the way to receiving the recognition she deserves

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025

News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025