Found in Translation: The art of celebrity casting

Madeleine Pulman-Jones considers modern casting in light of an unsung classic

When Pier Paolo Pasolini made his adaptation of Medea, the tragic Greek myth of a woman enticed away from her native land by the irresistible strength and beauty of a stranger, he cast legendary opera singer Maria Callas and Olympic triple jumper Massimo Girotti as Medea and Jason respectively. Had he made it in 2017 instead of 1969, he might have cast Rihanna and Cristiano Ronaldo.

Aside from being a surprisingly intriguing artistic choice, the 2017 superstar pair seems a relatively plausible casting in a world where a film like Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets can gross $221.5 million at the box office (despite reviews that were mediocre at best) thanks to its multi-hyphenate celebrity stars, Cara Delevingne and Rihanna. Though much is made of the superficiality of celebrity casting, with revered British actors periodically surfacing to make scathing comments about it in the press, what is often forgotten or misunderstood is its artistic potential. In a world where the celebrity is more and more a part of our intimate daily lives as a result of social media, the right kind of celebrity casting can harness the power of the society of the spectacle in order to elevate the message of a film to a meta-theatrical level.

“It is undoubtedly the faces of the non-professional actors which act as mirrors to our own sense of reality”

What ultimately makes Pasolini’s casting one of the most unexpected in cinema history is that it is incongruous with his famous predilection for non-professional actors. Born in Bologna in 1922, Pasolini was a generation-defining polymath. As a poet and filmmaker, journalist and painter, linguist and philosopher, Pasolini pushed the boundaries of ‘decency’ and made experimental films that dared to touch upon topics such as religion and sexuality, often in explicit and unconventional ways. In his filmography, the standout feature of which is his 1964 adaptation of The Gospel According to St Matthew in which Jesus was played by a teenage economics student and the Virgin Mary was played by Pasolini’s own mother (perhaps the most stunning example of self-deification in pop culture), the celebrity-led Medea is an anomaly.

Having received a lukewarm critical reaction upon its release, Medea still morphs and squirms under the probing microscope of the scholar or the critic. It defies classification in so many ways that it is almost tedious to note them. In selecting Callas and Girotti to portray Medea and Jason, Pasolini chose two of the greatest celebrity personalities of his day. Whether Pasolini was, as John David Rhodes suggests in his accompanying booklet to the BFI restoration, “attempting to warn the viewer of the perils of the modern world by presenting us with the image of two of its core players” or not is to some degree irrelevant. What Pasolini knew was that the closest thing in popular culture to classical heroes or heroines are celebrities.

It is fascinating watching Pasolini blend these celebrity faces with those of non-professional actors with his painterly touch. However, it is undoubtedly the faces of the non-professional actors which act as mirrors to our own sense of reality. As viewers we are led to ask ourselves, why seek out the artificial, the “modern,” when these raw, natural faces are so fragile and perfect? Ought we not to revere and protect this neorealist image of the “common man”? These are questions Pasolini raises in all his films, but particularly in Medea. We might even see Medea as a social and moral warning of sorts - a kind of meta-cinema that recognises us as voyeurs and almost dares us to confront our problematic distinction between the faces which we recognise as those of famous personalities and those which lead us to search for a deeper, more human connection.

When Medea arrives at Corinth, having killed her brother and fled her native land, she paces hurriedly and anxiously up and down the dry, flat earth and cries, “I don’t understand the sun!” This moment of exasperation is all the more evocative given that she is a sorceress directly descended from the sun god, Helios. Pasolini’s fascination with the relationship of his characters to the land they inhabit does not end there.

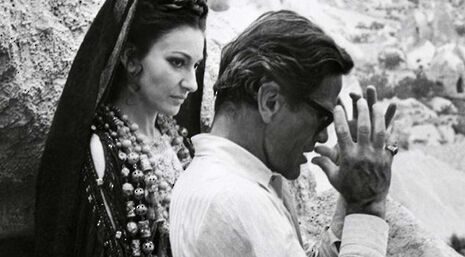

In extreme close-up, the face of Callas’ Medea, her head draped in dark blue fabric and rustic gold jewellery, resembles her native landscape of Colchis. The sharp lines of her nose and angular jaw even mimic the angular caves and churches scattered over the Turkish hills where Pasolini shot the film. By contrast, Girotti’s face could not possibly be more opposite – his is the rounded, calm, benign face of a man who is untroubled by the complexities of identity. Even in the love scenes this parallel is present.

Pasolini leads the camera as lingeringly over the half-clothed bodies of the lovers as he does over the barren landscapes. Just as the vividly coloured traditional dress of Medea’s people reminds us of the flesh being sacrificed and of blood already spilled, the protagonists’ bodies and faces become representative of their own homelands. These scenes are uncharacteristically restrained for the provocative Pasolini, though perhaps the fact that we are never shown Medea and Jason’s lovemaking reflects the ultimate tragic incompatibility not only of themselves, but of their cultures.

Medea was underappreciated at the time of its release, and remains an unsung classic – with the ever-evolving celebrity culture of today, now is a better time than ever to revisit this visual feast

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025 News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025

News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 Film & TV / Timothée Chalamet and the era-fication of film marketing21 December 2025

Film & TV / Timothée Chalamet and the era-fication of film marketing21 December 2025