Found in Translation: a birthday screening of Tarkovsky like no other

Reflecting on a very special cinematic experience, Madeleine Pulman-Jones found new cultural significance in a Russian masterpiece in the heart of St. Petersburg

In March this year, while living in St Petersburg, I came across a poster for an Andrei Tarkovsky retrospective at the Aurora, St Petersburg’s oldest cinema, in honour of what would have been the director’s eighty-fifth birthday. When I have seen Tarkovsky films on the big screen in the past, I have sat awkwardly in row E of a nearly empty cinema with a smattering of elderly visitors and a couple of young film enthusiasts. I had become accustomed to the anti-climax of logging on to book tickets for a one-off screening a week in advance and seeing that none of the seats had been booked yet. Why, I reasoned, should a Tarkovsky screening in St Petersburg be any different? I was well aware of Tarkovsky’s reputation in Russia, but after all, when was the last time I’d sat in a sold out screening of a film by a British art-house master? Sadly, it is rare for even Michael Powell or Derek Jarman to sell out a screen at a modern cinema.

“I realised how surreal it would be to walk out of this piece of architectural confection into Stalker’s grimy dystopian dreamscape”

In a Russian lesson a few weeks before, I had been asked to describe a favourite film of mine, and I chose Mirror (1975). My teacher was surprised I had seen the film, and told me that even in Russia not everyone liked Tarkovsky, turning to the rest of the class and explaining that he was a Russian director who made “weird, slow films.” Evidently I should have taken my teacher’s opinion with a massive pinch of salt, because when I went online to book tickets for the retrospective a week in advance, every single screening was sold out. Desperate, I woke up early and ran to the cinema on my way to school to ask whether they had any returned tickets. Miraculously, they had one ticket left to a screening of Stalker (1979).

This past year, snow showers persisted in St Petersburg until mid-May, and at the beginning of April it was still bitterly cold. On the day of the screening, I took some kasha (buckwheat) from the stove, wrapped up warm, and headed off to the cinema alone, feeling decidedly Dostoevskian. Opened in 1913, the cinema’s exterior is pastel pink with tall white columns – plucked straight out of Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel. I had not been expecting anything nearly as atmospheric as what I encountered when I entered the building. The foyer contains an old fashioned kiosk where, in addition to the staple popcorn and nuts, one can buy macaroons, pastries, and cocktails. With a winding marble staircase leading up to a velvet covered lounge area to boot, the cinema is drenched in pre-revolutionary opulence. Even then, caught up as I was in the romance of the moment, I realised how surreal it would be to walk out of this piece of architectural confection into Stalker’s grimy dystopian dreamscape.

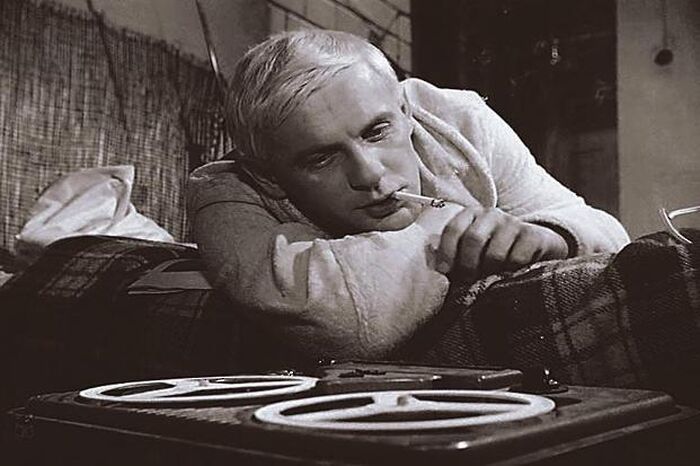

Tarkovsky was the son of Russian poet Arseny Tarkovsky, and trained at VGIK, the state school of cinematography, in Moscow. His debut film, Ivan’s Childhood (1962), about the life and dreams of a child soldier during the German invasion of Russia in WWII, established him as one of the most innovative filmmakers of his day. Tarkovsky made only seven feature films before his premature death from lung cancer, each of which has been proclaimed a poetic masterpiece. Chronologically, Stalker falls in the middle of his filmography, the penultimate film he was to make in the Soviet Union. Loosely adapted from the novel Roadside Picnic by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, the film tells the story of three eminent men who have paid a great deal of money to be taken by a ‘stalker,’ into ‘the zone’ – a mysterious area where it is said that one’s deepest wish will be realised.

Within minutes of my arrival at the Aurora, hundreds of people of all shapes, ages, and sizes flooded into the cinema. I had no idea how large the cinema was going to be, but I had certainly not expected this (I later discovered that the main hall seats around six hundred people.) I dashed to my seat, only to find that there was to be a pre-screening lecture by a film historian. The lecturer gave a brief summary of Tarkovsky’s place in the canon not only of Russian but of world cinema, as well as describing the fraught conditions of the filming process during which Tarkovsky’s favourite actor, Anatoly Solonitsyn, became exposed to toxic fumes as a result of which he died three years later.

As the film began we, all six hundred of us, lost ourselves in ‘the zone’ for nearly three hours. When the end credits rolled, the entire cinema clapped furiously and gave a long standing ovation. It was a cinema moment like none other I had experienced. This was not a gala screening at Cannes, Venice, or Berlin, but a relatively ordinary screening which was full not of critics and professionals, but true film fans. I hasten to add that the ticket itself cost me little more than four pounds due to the remarkably affordable ticket prices for cultural events in Russia. At the core of this effort to make culture accessible is a profound respect for art which has persisted to this day, from the cultural elitism of imperial Russia to the use of art as a unifier under communism – and remains a true outlier in the otherwise bleak Putin regime.

Luckily, Stalker and the rest of Tarkovsky’s oeuvre are no longer accessible only via such retrospectives, and are becoming increasingly accessible via DVD/Blu-Ray and legal streaming sites. For those looking for either an introduction to his work or a high-quality edition of one of his films, Artificial Eye and The Criterion Collection are in the process of releasing restored editions of his films with plentiful special features

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025

Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025