Zoetrope: Pixar’s humble beginnings

Ian Wang retells the story of Pixar’s modest start-up, and the battle the studio had fight to release its first, and life-saving, feature film – Toy Story.

When Toy Story first debuted in American cinemas in late 1995, it was a watershed moment in film history. No studio had ever made a feature film that was fully computer-animated before, let alone one that was so successful – the film grossed over ten times its original budget. Since then, of course, computer animation has become the dominant style in the animated film industry, and Pixar has become one of the most consistently lauded film studios in the world. But it can be easy to forget how humble the company’s origins were: their path to international renown was a tempestuous one, which would not have been possible without the enduring perseverance of its founders – and Steve Jobs.

"So many things in the film industry are contingent on nothing more than the amount of money one has in one's pocket"

Although Pixar was not technically founded until 1986, the company’s history really begins in the mid-1970s, in classroom A113 of the California Institute of Arts, which hosted the animation program attended by future directors John Lasseter (Toy Story, A Bug’s Life, Cars) and Brad Bird (The Incredibles, Ratatouille). If that number seems familiar, that is because it has been included in every Pixar film as an Easter egg – most notably, it is the directive given to the Autopilot in Wall-E that tells it to prevent humanity returning to Earth.

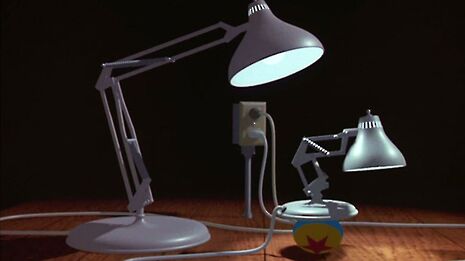

When Lasseter joined Pixar a few years after graduating, it was a part of Lucasfilm’s Computer Division, a group set up by George Lucas to develop advanced computer software for use in his films. When the company sought to become independent in 1986, Lucas sold the group to Steve Jobs, who had recently resigned from Apple. This was the same year that Pixar released one of its most iconic shorts, and Lasseter’s directorial debut, Luxo Jr., a whimsical 2-minute film about that little desk lamp that hops on the ‘I’ in Pixar at the start of all of their subsequent films.

It would be easy to draw a straight line from Luxo Jr. to Toy Story and assume that it was smooth sailing from 1986 onwards. Pixar certainly had some major milestones along the way: in 1988, they released Tin Toy, the first computer-animated film to win an Oscar; the same year, they debuted their RenderMan software, which earned them a technical Oscar several years later; perhaps most crucially, in 1991 they signed an agreement with Disney to distribute a computer-animated feature film, which ended up becoming Toy Story.

The reality, however, is that Pixar suffered numerous difficulties and setbacks in the intervening years. Pixar’s Image Computer, for example, the company’s first major project after Jobs took over, sold abysmally – it was hugely expensive, over $100,000, and only sold 120 units in its first two years on the market. Later in 1991, the company laid off 30 of their employees, including their President. Although during this time the animation department managed to turn a modest profit, mainly through creating TV adverts for companies like Listerine, the rest of the company was haemorrhaging money; Jobs was rumoured to have invested $50 million in the company just to keep it afloat. In an interview in 1995, Jobs said, “If I knew in 1986 how much it was going to cost to keep Pixar going, I doubt if I would have bought the company.” Pixar was, essentially, on life support.

Even Toy Story suffered a difficult production history, and was far from a sure-fire success. Disney was concerned that the film would be perceived as too childish, and pressured Pixar to make the film edgier, more adult. As a result, the early drafts of the film are almost unrecognisable, portraying Woody as a sarcastic, cynical villain whose behaviour provokes a rebellion from the other toys, a far cry from the charming hero we know him as today. Everyone, Disney included, thought the film was a complete mess, and they were nearly forced to shut the project down. Only after Pixar went back to the drawing board completely, and wrote a new script from the ground up, did they get the green light from Disney’s executives. The film was completed within a year, and the rest is history.

As a fan of the company, I find this origin story fascinating. But it also strikes me as a little sad that, if Pixar had come any closer to financial ruin, or if Jobs had been a bit less generous, we would have missed out on so much fantastic animation. It is a reminder that so many things in the film industry are contingent on nothing more than the amount of money one has in one's pocket. It is also an encouragement to look a little deeper into cinematic history, to see what other innovations might have taken place if certain creators had been blessed with the same luck (and wealth) as Pixar was

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026 News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026

News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026 News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026

News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026 News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026

News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026 News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026

News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026