Zoetrope: Shedding light on The Illusionist

For his third column, Ian Wang considers the morally challenging backstory to a beautiful animated film based on French director Jacques Tati

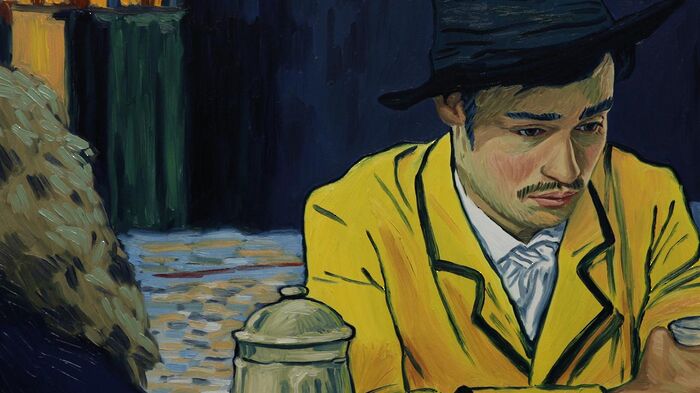

In Sylvain Chomet’s 2010 animation The Illusionist, a French stage magician struggles to make ends meet in 1960s Europe, moving from city to city to find work, performing his routines in increasingly tawdry venues to dwindling audiences. In the process, he inadvertently becomes the father figure to a naïve young Scottish girl who believes his magic is real, and tries desperately to take care of her after she follows him to Edinburgh, despite his failing career. It is a beautiful, lyrical film, full of loneliness and elegiac longing, with a gorgeous art style. It also conceals a dark family secret about one of the twentieth century’s most respected filmmakers.

“The film world was left blissfully ignorant, and his troubled past did not resurface until decades after his death”

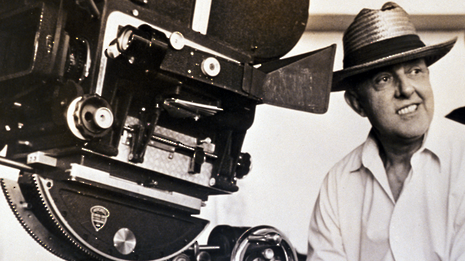

Let us back up a bit. Before legendary French comic director Jacques Tati made his first film, he was a cabaret performer at the Lido de Paris, trying to make a name for himself and getting the occasional cinematic role. There he had a brief relationship with fellow performer Herta Schiel, which ended with Schiel pregnant and Tati paying her so that she would sign a legal document relinquishing him of parental duties, thereby disowning his first daughter and leaving Schiel to fend for herself.

Tati’s abandonment of Schiel and his daughter, who he never had contact with despite several requests on her part, is generally treated as a historical footnote in the life of one of France’s most acclaimed and revered directors. Tati made only six feature films in his lifetime, but he is consistently ranked highly in lists of the greatest directors in history, sometimes compared to beloved silent comedians like Charlie Chaplin. Although some of his old music hall colleagues knew of his actions towards Schiel, most of the film world was left blissfully ignorant, and his troubled past did not resurface until decades after his death, when a long-forgotten Tati script was uncovered by his second daughter, Sophie Tatischeff, and handed to animator Sylvain Chomet – that script eventually became The Illusionist.

The film’s release, unsurprisingly, was met with some controversy. Enter Richard McDonald: the son of Helga Marie-Jeanne Schiel, the daughter who Tati disowned. When the film first debuted at Cannes, McDonald wrote a scathing letter of condemnation, published in The Observer, accusing Chomet of “sabotaging…Tati’s original L’Illusioniste script”. McDonald argues that Tati’s script was written as an act of remorse for his treatment of Helga Schiel, and that the troubled father-daughter relationship portrayed in the film is an analogy for his own failures as a father. This detail, however, is conspicuously absent from the film itself. Nowhere does Chomet offer a dedication to Schiel, or any kind of historical note – this enraged McDonald, who said it “subverts the man’s only redeeming response towards his daughter”.

Chomet, for his part, rejects the entire notion that the script was written for Schiel. When recounting a meeting he had with McDonald prior to the film’s release, he quotes himself as saying “I don’t see any reason why this script should have been dedicated to this girl [Tati] never lived with and who he didn’t see growing up”. Chomet, instead, suggests that the film was written for Sophie Tatischeff, Tati’s aforementioned second daughter – indeed, the one dedication that does appear in the film is to her – and he has dismissed the coverage of McDonald’s claims by The Observer and other newspapers as “very bad journalism”.

This war of words between Chomet and McDonald interests me because it seems to be a convergence of so many different debates about art and about artists. If we suspect an artist of great moral wrongdoing, for example, how do we go about appraising their work? How do we figure out the intentions behind a piece of art if the artist in question has been dead several decades? How do you adapt that piece of art from a textual medium to a visual medium? And who has the right to decide these things?

In the case of The Illusionist, I cannot say that there is a simple answer to any of these questions. If Tati really did abandon his first child in the way that McDonald alleges in his letter, he is not someone I would have respect for. I also cannot say, therefore, if I believe that Chomet should not have made his film. Nevertheless, I liked the film a lot when I first watched it, although my opinion changed once I discovered more about the sordid history behind it.

While I may not be able to answer these questions, I think they are worth asking. It can be too easy for audiences and critics to get caught up in a narrative of auteurist brilliance when discussing a canonised figure like Tati, but the reality is that those figures are just as flawed and prone to cruelty as the rest of us, and that reality needs to be engaged with. Taking Chomet’s route and choosing to dismiss anyone who critiques his specific interpretation of Tati’s work is, I think, intellectually dishonest, and ultimately does his own film a disservice

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026 News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026

News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026 News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026

News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026 News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026

News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026 News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026

News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026