Close-Up: On the Waterfront

Allanah Lewis unearths this 50s classic and asks to what extent Elia Kazan’s drama absorbs his politics…

In 1952, 2 years before his film On the Waterfront won 8 Academy Awards, the director Elia Kazan testified before a House Committee on ‘un-American activities’, naming the names of several associates from his days in the Communist party. His involvement hadn’t survived beyond the 1930s but by testifying Kazan broke a golden rule: never rat on a friend and always keep your mouth shut. In Hollywood circles he was denounced as an informant and never forgiven. Outside of Hollywood circles he was a Red and a Soviet sympathiser. And still never forgiven. On the Waterfront, Kazan’s 1954 masterpiece, shows him coming to terms with both. It’s a shame that he never quite manages to. To all involved, Kazan ‘squealed’. And though he might have succeeded in justifying that to his audience, he never quite seems to justify it to himself.

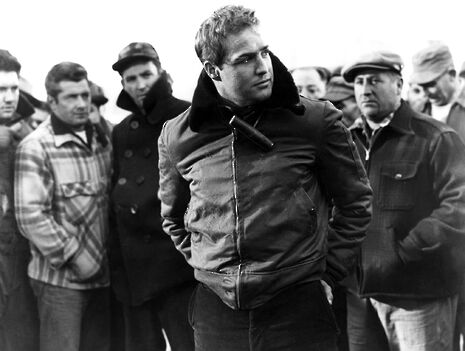

On the Waterfront is a film as much about conscience and redemption as it is about realising that the two don’t match up. “Conscience,” as Terry Malloy of Holboken, New Jersey testifies, “that stuff can drive you nuts” (and if any character in the history of cinema knows it, it’s Terry). The setting of the film is contemporary, documenting the lives of dock workers and their corrupt union bosses. Life for the longshoremen is simple: their pay is bad and their working conditions worse because both are controlled by an unscrupulous racketeer who decides who works and who doesn’t. Few dare to speak out. At the beginning of the film, we see the protagonist Terry (Marlon Brando)- ex-prize fighter and inadvertent darling of the mob- lure a union-snitch from hiding. The man is killed by two thugs who push him from the top of a tenement building. Terry is apalled, but told to forget about it: the snitch had it coming. It gets better. Terry’s brother, Charley, is an accountant for the ‘waterfront gang’, so easy work is guaranteed as long as he keeps in good favour with the racket boss. Eventually, Terry is faced with a subpoena from the police, encouraging him to come forward and testify against the gang. By degrees his conscience is drawn out by local priest Father Barry and young nun Edie (crucially Terry’s love interest and the sister of the man that Terry is responsible for killing- making for an awkward first date). It’s a film remembered for it’s great lines and influential cinematography (one of the pivotal scenes is a silent conversation between two characters). Less so for its controversial history.

On the first page of Kazan’s script was written:

PHOTOGRAPH

The inner experience

OF TERRY

And, in spite of it having the conventions and cliches of a motion picture, On the Waterfront still feels like a documentary. The bite of the wind does wonders for the actor’s faces in that it makes them look less like actors and more like people. The physicality of Brando’s acting (the kind of thing seen later in The Godfather with the cat on his lap and the water-pistol scene in the garden) does away with overwrought mannerisms- something which could make his simple character look otherwise less than human. Even when Terry’s brother Charley is forced to pull a gun on him, he pushes it away gently as though patting his hand. “It’s alright,” he seems to say, “I know you don’t mean it”. Terry interacts and probes his environment as though, like a child, he is somehow lost in it. His transformation is interior and he is all too aware that it is, as yet, incompatible with the exterior world. Admittedly the final few scenes are poetic, taking on a kind of Passion of Christ vibe- a contrivance which doesn’t translate well today. The famous “I coulda been a contender” line is difficult to hear anew, but sadness- not just Terry’s, but his brother’s too- pervades the scene in a way which feels comfortingly verisimilar.

“It’s a film remembered for it’s great lines and influential cinematography... Less so for its controversial history”

His deep unpopularity in left-wing circles did not stop Kazan from producing a socialist film. In fact, when first watching it, I was taken aback, or at least interested enough to watch it again. The film is timeless, but depressingly so. Wage slavery is alive and well. The racketeers take their cut and allow nepotism and bribery to rule business. The mob, whilst acting outside of capitalist circles, is still based on a violent capitalist model. And Father Barry and Edie do not so much represent Christian morality as they do morality itself, encouraging the longshoremen to speak out. In one scene, when Terry admits his feelings for Edie, she is quick to steer the conversation from romance to conscience. Love in the film is an accessory, a necessary convention of fiction, but not the main component of either Kazan or Terry’s story.

In his 1988 autobiography Life, Kazan writes: “The only good and original films I’ve made were after my testimony”. Perhaps, for him at least, it’s true: after 1952 Kazan begins to star in his own films without realising it. I think of a moment towards the end of the film when a union boss shouts at Terry, “You ratted on us, Terry” and Terry shouts back, “I’m standing over here now. I was rattin’ on myself all those years. I didn’t even know it.” It brings me to my final point: On the Waterfront is a film about failure. About what ‘coulda’ been, but wasn’t. About whose fault that is or if indeed it is our own. It is not a plea for forgiveness from Kazan. It’s a self-performed dissection of one man’s conscience, his sacrificing of comfort for morality, whilst being aware that redemption probably won’t come of it

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025

News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025 Features / ‘Treated like we’re incompetent’: ents officers on college micromanagement30 December 2025

Features / ‘Treated like we’re incompetent’: ents officers on college micromanagement30 December 2025 News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025

News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025