VisCourse: The possibilities of children’s literature on-screen adaptations

What makes children’s literature children’s literature? And do we impose mature themes when we adapt it for the screen? Danielle Cameron meditates…

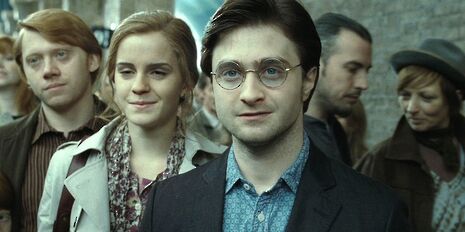

Pursuing a universally agreed-upon definition of children’s literature is tricky. Is it a literature defined by the youth of those who read it? If so, all of us simply must have lost interest in J. K. Rowling or Philip Pullman upon waking up on our eighteenth birthdays and finding ourselves magically transformed into adults (in the legal sense, at least). Is it a literature defined by the youth of its protagonists? If that’s the case, then why is Uzodinma Iweala’s story of child soldiers in Beasts of No Nation not available in the children’s section? For the purposes of this discussion, I am proposing that children’s literature and children’s film are literature and film predominantly (but not solely) marketed to a readership under the age of eighteen. Alice in Wonderland, Mary Poppins, Jumanji, Twilight, The Hunger Games and, of course, the Harry Potter series all began life as books marketed to younger readers. However, they were all given further chances to capture audiences’ attention in on-screen adaptations.

Book to screen adaptations are often treated with caution, if not scepticism. George Bluestone surveys the relationship between literature and film as being both “overtly compatible” and “secretly hostile”. This compatibility lies in the lure of trying to capture the reader’s imaginings onto celluloid; the hostility is provoked when realising that these attempts may never please everyone. Deborah Cartmell argues “there will be higher demands on fidelity” when it comes to children’s literature adaptations. However, these higher demands on fidelity have not discouraged filmmakers in their attempts to cast children’s literature onto the big screen. Out of the top hundred grossing films worldwide in 2016, nearly one in four were children’s films. Furthermore, a third of those films were adaptations.

“Screen culture is becoming better at recognising the intricacies of books often segregated to the back walls of bookshops and is keen to broadcast these overlooked complexities”

When contemplating the popularity of screen adaptations of children’s literature, it is tempting to look at the possible ‘adultification’ of the source texts. As parents are often the ones buying cinema tickets for their children, studios must be making their adaptations as appealing as possible. However, to suggest that filmmakers always try to augment or ‘adultify’ children’s literature to better suit a cinematic audience of all ages is to overlook the complexities already present in children’s books. As an experiment, re-read some of the books that you read at school. Do not be surprised if you find a lot of them to be written in a dual address that you did not notice before: with content to please a child but in a style and with a wink that interests the adult. After all, the text may have been written for children or teenagers but it was written by an adult. Book to screen adaptations often simply extract this dual address with its complexities and make them more apparent. Therefore, the ‘adultification’ of children’s books into film pertains less to making children’s literature more sophisticated but, rather, encourages a wider audience to recognise the value of children’s literature as a whole.

However, as the generation who experienced Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone as eleven-year olds in 1997 turn thirty-one this year, perhaps they and subsequent generations need fewer reminders of the importance of children’s literature. Love it or loathe it, Rowling’s creation was a watershed moment in the appreciation and understanding of children’s literature. The return and popularity of the wizarding world in both The Cursed Child and Fantastic Beasts last year spoke to the fact that fans may age, but they do not necessarily lose interest. Nostalgia is inherent in this popularity but it is not its sole function. On-screen adaptations can perpetuate or inspire this interest: I dare say that many of us have introduced younger family members to the Potter universe through the inevitable Christmas reruns of the films. With the generations who have grown up with a proliferation of newly published children’s literature and the commercial rise of young adult literature, filmmakers are increasingly likely to find audiences willing to pay to watch adaptations.

The recent long-form TV adaptation of Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events is testament to this evolving demographic. As those who queued for the midnight release of The Deathly Hallows grow older and their disposable income grows larger, studios and filmmakers are catering to these changes. Aside from Snicket, the adaptations of children’s or young adult literature already released this year or scheduled for release this year include: A Monster Calls, Wonder, An Ember in the Ashes, A Wrinkle in Time and Netflix’s adaptation of 13 Reasons Why. This does not mean that audiences are remaining childlike in their tastes, nor are filmmakers simply ‘adultifying’ simplistic texts. Rather, screen culture is becoming better at recognising the intricacies of books often segregated to the back walls of bookshops and is keen to broadcast these overlooked complexities

News / Cambridge bus strikes continue into new year16 January 2026

News / Cambridge bus strikes continue into new year16 January 2026 News / Uni members slam ‘totalitarian’ recommendation to stop vet course 15 January 2026

News / Uni members slam ‘totalitarian’ recommendation to stop vet course 15 January 2026 Science / Why smart students keep failing to quit smoking15 January 2026

Science / Why smart students keep failing to quit smoking15 January 2026 Interviews / The Cambridge Cupid: what’s the secret to a great date?14 January 2026

Interviews / The Cambridge Cupid: what’s the secret to a great date?14 January 2026 News / Local business in trademark battle with Uni over use of ‘Cambridge’17 January 2026

News / Local business in trademark battle with Uni over use of ‘Cambridge’17 January 2026