The quiet saboteur: when misogyny comes from within

Grace Howell explores how female students are learning to reshape their inner voice and silence their internalised misogyny

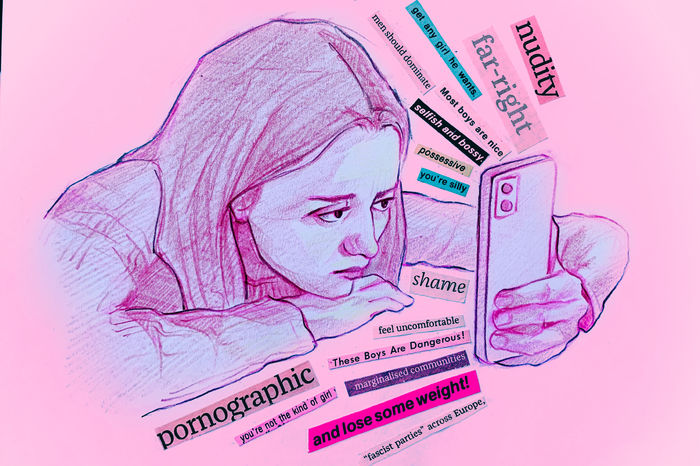

What happens when the loudest critic, the deepest prejudice, isn’t found in the boardroom or the classroom, but within one’s own mind?

The little girl who is told she is bossy, not as proficient in sports, and not a leader has her self-perception warped. The inner voice, which begins as a whisper, becomes fed and nurtured by passing comments and everyday exclusions, but also news stories of other women being discriminated against, a reminder that ambition and visibility can be punished. Over time, this inner voice becomes something else entirely: the internalised misogynist. While external sexism is often called out and challenged, this inward prejudice is harder to name and even harder to silence.

“Over time, this inner voice becomes something else entirely: the internalised misogynist”

Martha, described how when she leads, she “doesn’t want to upset anyone and doesn’t want to be accused of being bossy”. Even though no one may be prejudiced against her, her internal voice makes it so, constantly dredging up any past negative experiences. Therefore, whenever she struggles to have her opinion heard, it becomes an “emotionally exhausting” task to overcome this internal voice. This constant battle for legitimacy leaves her drained and questioning whether it’s worth continuing. When this discrimination occurs, it gives that inner voice credit and another fracture in her confidence.

The internal critic is not always based on what others in the room think, but on what the woman fears they might think. Emily, a theatre director, describes how she felt choked with silence, depicting the mental cost of being a leader. For her, it was also the constant internal pressure to be perfect; when making a mistake, she argued, “you set yourself up for the frailties that they think you have”. The internal voice demands perfection because when that is not met, a woman’s perceived ‘weaknesses’ become real.

“You set yourself up for the frailties that they think you have”

Sophie, a sports captain questioned the “legitimacy of her being at the table with other men” for her sport. Women being ambitious in sport, theatre and the classroom is viewed as threatening and her inner voice reinforces the very stereotype she wants to escape. Emily’s ambition became something to be ashamed of. She said women are you made to be, “digestible,” easy to accept and unthreatening, because “we cannot have it all: being feminine, successful and a leader”. Yet we must question and reflect whether the voice urging us to be “digestible” is only external, or whether it includes our own.

Despite the presence of that inner voice, the women I spoke to have reached a place where they can assert themselves as leaders and begin to reshape their internal narratives. They are learning not only to take up space, but to feel comfortable doing so, to believe in their legitimacy as female leaders.

“these women are creating space for themselves and other women to follow”

Isabel explained how she used to feel “more withdrawn” when facing discrimination as a theatre director; however, her experience has enabled her to be clearer in speaking up when she has been disrespected. From my own experience, I’ve seen how women often adapt to prejudice by modifying their behaviour, becoming more accommodating and less visible, which reinforces the misogynistic belief that they must shrink themselves to succeed. However, Isabel demonstrates how the inner voice can be quietened, and with each experience of being a leader, she can be confident in expressing herself unapologetically. To create change in our university, these women are creating space for themselves and other women to follow. Yet, they also make mental space to see themselves as effective leaders and inspire those around them to do the same.

For Emily and Sophie, female friendships are key in mitigating this inner voice. Emily described having to make a difficult decision alongside another female leader: after talking together, they realised their hesitation came not from the situation itself, but from the lingering voice of internalised misogyny. Sophie echoed Emily’s words on the importance of female “sisterhood” and works hard to ensure every woman has a place in her team.

It was this collaborative approach that I found particularly inspiring. Having navigated prejudices and battled their own internal voice, each of the women I interviewed had developed an empathetic leadership style. They expressed a desire for collaboration rather than competition; for Isabel, “the best way to get the most out of your team is to make them feel valued” and for Sophie, the importance of “making sure every woman has her place” is paramount. These women are determined to ensure that none of the women who come after them will ever have to fight to earn a seat at the table.

The deepest prejudice can sometimes be the internal voice questioning a woman’s right to lead. As society slowly rewrites the external narrative around women in power, we are also rewriting the internal one. These women prove that leadership isn’t just about taking up space but believing you deserve to.

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Gov grants £36m to Cambridge supercomputer17 February 2026

News / Gov grants £36m to Cambridge supercomputer17 February 2026