Vintage Varsity: International Women’s Day

Resident archivist Anna Herbert investigates the experiences of women at Cambridge through the years

When Varsity was established in its current form in 1947, women’s existence in Cambridge was marginal, informal and insecure. It was not until a year later, in 1948, that the first Cambridge degree would be granted to a woman, after previous proposals several decades earlier had been rejected, accompanied by violent protest. The awarding of an honorary degree to Her Majesty the Queen marked the ‘triumphant culmination’ of ‘seventy years of bitter struggle for equality’. The Queen’s special message to the women of Cambridge suggests, however, that there was still an uphill struggle ahead for women to assert their academic legitimacy. The Queen highlighted that attending Cambridge could add “the grace of a well-trained mind” to a woman's “natural” “gentleness, ready sympathy,” and “an instinctive love of the young, weak and the suffering.” Women’s position at the University may have been formalised, but it was still heavily gendered.

The true marker of women’s formal entry to the University was reported by Varsity just a week later, when a Girton student became the first female undergraduate to be “prorogued” after being caught not wearing a gown after dark. Valida Turner was quoted saying “It was worth six-and-eightpence to make University history.” She was the first to succeed in acquiring a “historic progging,” beating the competition evident in the “frequent reports of attempts by Newnham and Girton women to attract the attention of the Proctors.”

Varsity’s historic attitude towards and portrayal of women has reflected the antiquated misogyny that is inseparable from Cambridge’s past. The ‘Girl of the Week’ column that frequented Varsity prints saw women being spotlighted for their “feminine” qualities. One ‘Girl of the Week’ in 1963 was selected due to her being “extremely charming” and the most “beautiful Icelandic girl in Cambridge.” Another column, ‘Woman’s Angle,’ provided readers with a weekly insight into the fashions of the late 1940s. Whilst women entered Cambridge in pursuit of intellectual improvement, they were unable to escape the rigid societal standards of femininity.

One article complained that the college took “advantage of the fact its members are all women” in expecting them “to do the housework”

The ‘Women’s’ page of Varsity papers of the '60s saw weekly recipes, no doubt to encourage the continued domesticity of female students. In 1949, “Domestic science” at Newnham was labelled as “the essential study which no student escapes.” One article complained that the college took “advantage of the fact its members are all women” in expecting them “to do the housework,” while they still had “just as much work to get through as the men.” Women may have formally gained the same status as men in the university, but their experience was by no means one of equality.

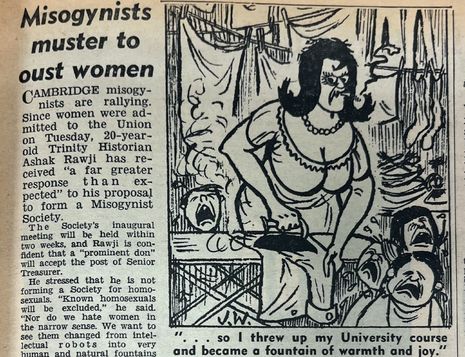

The Union existed as a stronghold for the continuation of male domination in the University. In 1955, Varsity reported on the creation of the Cambridge University Women’s Union in response to the Union’s persistent exclusion of women. The first debate, “That Women’s Place is in this House,” left the House “equally divided,” only passing in favour on the casting vote of the President. Eight years later, women were finally admitted as Union members. The backlash of women’s inclusion culminated in a Trinity Historian proposing to form a ‘Misogynist Society’ as an “active pressure group,” with the aim to change women from “intellectual robots into very human and natural fountains of warmth and joy.”

By the latter half of the 20th century, the women’s colleges had established themselves as strongholds of women’s education. But the further expansion of the female student body could only come through the emergence of co-education and co-residence. The introduction of women was a slow and fractured process amongst colleges, a process encapsulated by endless Varsity reports on the possibility of various colleges admitting women. In 1973, a Varsity article titled “Gentlemen do their business in private” highlighted the deep-rooted barriers to co-residence. Queens were revealed to be resistant to introducing women to the college due to fears it would “stop Cripps,” a key college benefactor, “from paying up” to fund the extension of the college. The college’s President also acknowledged that “the old Queensmen” were “strongly against the admission of women.” The integration of women into mixed colleges was by no means a simple process, representing a power struggle between the traditional segments of Cambridge and voices of progress.

The Varsity archives paint two distinct pictures of women’s progress within the University. On one hand, the newspaper is rife with misogyny, both in reports of Cambridge’s resistance to women's full inclusion, but also in the casual bigotry of articles and columns of the past. Yet, in between these exist articles representing hope and progress, as women were, albeit slowly, able to establish themselves in the University and legitimise their existence within the student body of Cambridge.

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Gov grants £36m to Cambridge supercomputer17 February 2026

News / Gov grants £36m to Cambridge supercomputer17 February 2026