Fight for your Rights

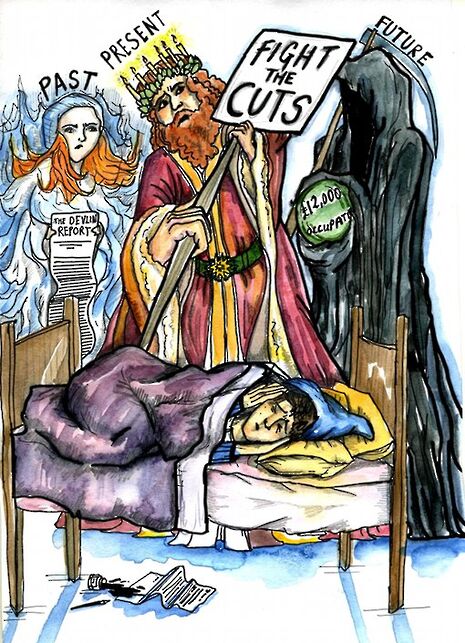

Morgan Wild, CUSU-GU’s Student Support Officer, tells us why we shouldn’t take the spending cuts lying down.

In 1972, hundreds of students flocked into the Old Schools, the centre of administrative power in Cambridge, demanding that students had a measure of democratic control over the University and over decisions made by the University that affected them. Their list of demands was long and not all were achieved – the Proctors, the gowned University discipline force, are still with us and the ultimate control of the University is still in the hands of a democracy of academics, not students. However, one particular demand transformed the power of the student body, and has had far reaching and important consequences to this day.

The Old Schools occupation was a profound challenge to the power relationship between students and the University. As a result of the occupation, the University published the Devlin Report, which recommended that students have representation on the University Council, the primary decision making body of the University. After further exhaustive discussions and deliberations, students were finally given a voice in the decisions of the University.

This achievement transformed the collective bargaining power of Cambridge students: from it, student membership of nearly all the committees that govern the University and the colleges followed and the student union was eventually officially recognised by the University. Much, if not most, of the work that CUSU does today in representing students, lobbying the University and securing change for its members would be impossible without that initial victory.

The activist approach that helped to achieve this victory is more relevant than ever before. When effectively and intelligently done, it can continue to play a significant role furthering the student interest. We are currently facing the biggest political knife fight the student movement has ever seen and only through an approach that combines direct action with the more traditional tools of the student movement can we succeed in winning it.

Activism is a perspective that advocates taking direct action to achieve a political goal. It encompasses the traditionally lefty gamut of protests, demonstrations, occupations and strikes to achieve socially desirable ends – those approaches that have variably fallen into a state of disuse and disfavour in our modern, responsible political age, but that students need to meet the challenges that we face.

There have been many achievements in Cambridge that have been enabled by collective student direct action, as even the briefest of sojourns into the Varsity archives reveals. The 1977 occupation of the Senate House by student parents helped secure University funding for the first time for crèches and nurseries; the occupations of the Lady Mitchell Hall and the Economics Faculty in the 70s, helped deliver substantial examination reform of the Economics Tripos, for the first time allowing students to submit dissertations. The New Hall rent strike in 1973 delivered a rents freeze; the rent strike at King’s in 1979 made King’s publish its investments and partially disinvest from South Africa; the university wide rent strike and campaign in 1999, led by CUSU, helped ensure that rent increases were negotiated with college JCRs. More recently, the “Penny the Vice Chancellor” movement for socially responsible investment secured (admittedly, in a tepid form) University agreement to balance ethical considerations when making investments decisions. I could go on.

However, activism has fallen out of favour in Cambridge and the wider world, as people have become disillusioned with its ability to deliver. Those of us who advocate it as an approach only have ourselves to blame, through the silly sectarianism, the grandiose claims about the demise of capitalism, the poor strategic thinking and planning and occasional straight out stupidity that plague the organised activist movement and severely curtails its ability to make meaningful political contributions.

Activism can become again an effective political force that can play a part in securing significant changes for Cambridge and for the wider student movement. However, it requires clear and concrete goals and a realistic plan to achieve them. Too often the answer to the question “Why are we doing this?” or “What is this protest supposed to achieve?” is “well, we’re showing solidarity”. Activism risks being emptied of strategic meaning and purpose. These vague affirmations of solidarity allow us to protest and parade and picket, without any clear conception of what it is we want to achieve and how we are going to achieve it.

Protest has too often become for the left what a fox hunt is for your local Conservative Association: an opportunity for us to socialise, get together and chat, rather than a serious attempt to change society and our objectives suffer from this lack of clear thought and political strategy. An attitude of “This is wrong, we’d better have a protest about it” simply will not do. Activism is exhausting and often boring - we cannot afford to waste energy on protest for the sake of protest.

For all the flaws and failings of the activist approach, if we want to achieve lasting change in this University, this city and this society, then a serious part of our approach must be to protest, demonstrate, occupy, and do so effectively. Change does not happen, or does not happen often, just by writing a letter to your MP or the Times, or lobbying your representatives, or through dutifully voting every five years. In addition to this, it requires broad based social movements, mass engagement and participation, targeted and effective direct action – it requires activism.

I do not want to argue that it is only through collective protest that gains are made, nor that collective action is sufficient in and of itself. This sort of action will not deliver lasting change in isolation – occupations, strikes and protests will not work if they are considered the only tactic worth pursuing, as if the act of demonstrating student opposition, through some mystical process, will magically transform the University. Other tactics are necessary as well. All of the actions I have mentioned were part of a wider strategy to achieve particular goals – students were not protesting for the sake of it, they were engaged in a broad campaign, involving lobbying the University in traditional ways as well as making life difficult for them through direct action. Direct action, however, was central to their success: activism has delivered results for us in the past, and it can deliver them again.

We face a situation where the entire future of the higher education sector is under threat: where up to 80% of funding could be cut and tuition fees could hit £12,000. This is the biggest fight the student movement has ever faced and, for the sake of future generations of students, we cannot countenance the possibility of failure. We will not succeed just by trying to pick off a few weak Lib Dem MPs through lobbying; nor through pleading for the worst excesses of the Browne Review not to be implemented.

We will only succeed if we create a political atmosphere and culture where it is impossible for the current proposals to be implemented. The National Demonstration on the 10th November promises to be the biggest mobilisation of students in a generation and I encourage all Varsity readers to attend. But that will not be enough to stop this onslaught. We need to consider a range of action, including the possibility of nationwide occupations, rent strikes and demonstrations. To win this fight, we all need to become activists now.

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025

News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025 Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026

Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026