On being a Queer rugby player

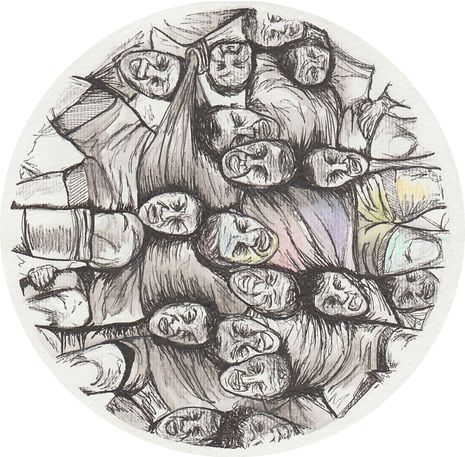

Callum Finnigan explores his changing relationship with rugby as a Queer person, delving into the profound ways in which the sport’s history continue to shape its present and highlighting issues which he feels must be addressed

Rugby has always been a part of my life.

For the last 15 years, I have watched rugby, I have been in rugby clubhouses, I have represented school, club, county, and – as of October 2020 – Pembroke College.

Concurrent to this ‘rugby life’ is my life as a Queer person. I ‘came out’ as bisexual in the summer of Year 10. Since then, it has been 5 years of new and constantly evolving feelings, identities, and labels. At the time of writing, I am decidedly a Queer person: in orientation, gender expression, and political conviction. And rugby has been present at every stage. It’s fair to say I have absorbed rugby’s culture, and listened to what it had to say about me.

Rugby has been a site of oppression. I left my second rugby club after 5 years, aged 17, amid a maelstrom of othering and ridicule. As my Queer identity was developing, so too was sharper bigotry, more flagrant homophobia in the air that I could no longer stand. Homophobia had always been present in club and school changing rooms, but increasingly it became targeted. Coaches and fellow teammates, wearing the same jersey I did, saw rugby as a space where I could not exist. It seemed being Queer and playing rugby were irreconcilable. Rather, I was in direct contravention to their understanding of rugby, what they held dear. I was other, unacceptable, a threat. I needed to go. I did.

“It seemed for once being Queer and playing rugby was tenable. I didn’t have to leave my sport behind”

But it has also been a space of refuge. I joined London’s Kings Cross Steelers (KXS) RFC in the summer after Year 13. Unsure of who I was, the words ‘I am gay’ still prickly on my tongue, KXS became a long-needed salve. Founded in 1995 as the world’s first queer club, I was surrounded by people unashamedly like myself, sharing my passion, for the first time in my rugby career. It seemed for once being Queer and playing rugby were tenable. I didn’t have to leave my sport behind.

These contrasting experiences might naturally lead you to question yourself: why was I unacceptable? Why was a young Queer player seen as so reprehensible? Dealing with such tough questions, I turn to a popular quip concerning rugby. “A hooligan’s game, played by gentleman’’. This pithy adage succinctly summates how rugby has been understood since its conception in 1823 at Rugby School. It has been popularly conceptualised as a sport built on contradiction. Physical hooliganism tempered by the acceptability of its participatory bodies.

To be a good player, one must take up space. It is a contact sport hinged on two principles: that of physical collision and taking up space. Bodies are crudely hurled in ‘tackles’ and aggressively warded off in ‘scrums’, ‘mauls’ and ‘rucks’. Rugby is rough, a potential playground for hooliganism. Yet, it remains conceived as a ‘gentleman’s game’, by virtue of who is allowed to play.

Created in the confines of one of the country’s foremost public schools, the sport’s origin is inextricably cast within the nexus of white, upper-middle-class England. A product of its origins, rugby is imbued with a didacticism. It coheres with a specific view of society, and how people and its players should behave. Rugby became a space for the elite — for white, middle and upper-class men to flex their literal and moral muscles. And, in the 19th-century, morality implicated a normative consideration of sexuality and gender expression.

These prototypic rugby players were painted as hegemonically masculine. To hurl one’s body against an opponent, but to respect said opponent and the rules of said hurling, became the pinnacle of desired masculinity. Operating within Judith Butler’s Heterosexual Matrix, if normatively masculine, the players must also be normatively heterosexual too. Masculine, also meant male, failing to recognise Jack Halberstam’s notions that masculinity is not a possession of male power, but rather is a plurality, that includes Queer and female masculinity.

“Awareness and inclusion must be considered a collective duty - sport in 2022 can no longer be an exclusive space”

A player’s deviation from the noble conception of male masculinity within rugby represents a deviation from the morality within which the nascent sport was conceived. It threatens the corrosion of its self-image.

As an increasingly open Queer rugby player at the age of 17, I was threatening the fabric upon which rugby had been cast. My existence transgressed the desired heterosexual masculinity which has shaped the sport for centuries. Behind every slur that I heard directed towards me, or vitriolic message in the team’s group chat, was a historical quaking, as they saw the sport’s image being chipped away. They feared that the imposition of ‘people like me’ threatened what rugby represented. I was and am a Queer person. I was a fearful outlaw, and rugby did not want me.

At the age of 20, now playing for both Pirton RFC (Pembroke & Girton RFC) and KXS, rugby remains a part of my life. Yet, so too does the dissonance between being queer and playing the sport. No longer in my own mind, this uneasiness in squaring these two worlds most certainly exists in the minds of others. I am still an outlaw, albeit an acceptable one.

And I am not the only outlaw. Rugby cannot be completely dislocated from its origins, however players today can actively challenge its legacy. Awareness and inclusion must be considered a collective duty - sport in 2022 can no longer be an exclusive space. Rugby cannot only be a game for gentlemen. It must be a community within which diversity is encouraged and those like myself, who defy its original framings, are welcomed. This is what I demand every Cambridge rugby player resolves to cultivate in this New Year and beyond.

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025 News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025

News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025 Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025

Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025 Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025

Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025 Interviews / Meet Juan Michel, Cambridge’s multilingual musician29 December 2025

Interviews / Meet Juan Michel, Cambridge’s multilingual musician29 December 2025