Blood is not thicker than water

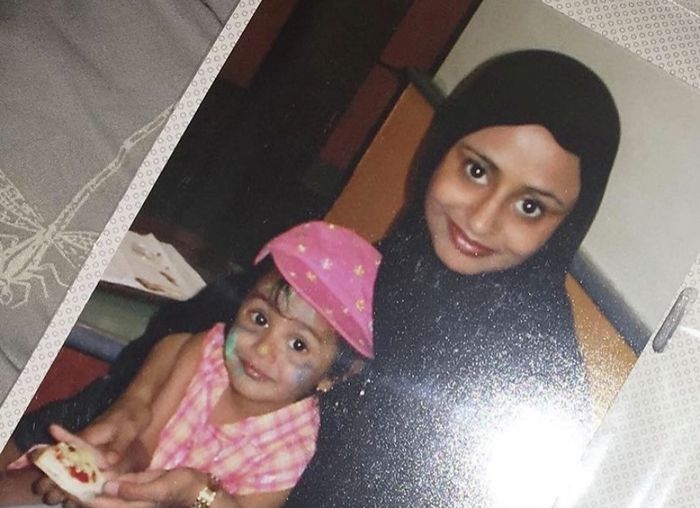

Digital Editor Alex Oxford explores her relationship with her mother and how a complicated diagnosis has caused her to reevaluate the meaning of blood relations

Content Note: this article contains discussion of emotional manipulation and detailed discussion of terminal illness.

I am a child of divorce. It’s hardly something I would label myself as. It’s not an identity for me, or a defining character trait: it’s a fact. For about a decade, my parents were frequently in and out of court, engaged in a long, arduous custody battle with many false accusations, a lot of emotional manipulation, and absolutely no desire for a Parent Trap-style happy ending. Much like a movie, the drama drew to a climactic final scene. In my case, it was on the 17th September 2012 at a court hearing which would finally dictate my custody arrangements.

On that day, I was at school. It was only a chance encounter in the reception area that informed me of what had happened. My mum, upon seeing me walking to the IT room, beckoned me to her, away from the rest of my class, and sat me down, clinging to me as she did. My headteacher was alerted when he heard her sobs echoing down the corridor, at which point he ushered me into his office and told me I would not be returning to my mum’s house that day. My dad came to pick me up, and I never saw my mum again.

In early 2013, approximately six months after I changed custody, I received a letter from my mum. She assured me that she didn’t “blame” me for what had happened and that, when I turned 18, she knew I would come and find her. As far as I was aware, this was the last contact we would ever have.

Until 2020.

“It made a mockery of my belief that blood is not thicker than water”

As we’ve all learned in the year of COVID, your situation can be flipped on its head in mere seconds and, on the 27th of October, it was clearly my turn. In a 14-minute-long Facebook call with a cousin I had not met since I was about six years old, I was informed that my mum was in hospital. She had recently been diagnosed with Huntington’s disease... and it was possible that I would be too.

Huntington’s disease is a genetic condition caused by a mutation in a person’s huntingtin gene, which is attached to the fourth chromosome. Since it is genetic, children of those with Huntington’s have a 50% chance of inheriting the condition themselves. The disease is also currently a terminal one, commonly described as having Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Motor Neurone Disease all at once. After onset (typically between the ages of 30 and 50), patients are given a life expectancy of 15-20 years.

It was as if that “not-The Parent Trap” movie had been commissioned for a sequel, as genetics brought my mum and me back together. It made a mockery of my belief that blood is not thicker than water. The closure that I thought I had with my mum was snatched away like ice cream from a toddler. All this time, there might have been a mutation in my chromosomes ready to prove that my mum, and the drama surrounding her, had never really left and, more importantly, that it never could.

After a visit home over the Halloween weekend, I finally replied to that 2013 letter. I didn’t mention any of its contents — for all I know it had been long forgotten — but it was etched in my mind as I was writing. My letter, much like this article, stuck to the facts: I am 21 years old, I study at the University of Cambridge, I am in my final year, etc… There was a striking lack of emotion for something so personal. Firstly, because I couldn’t for the life of me explain how I was feeling at that point, and secondly, because I was reentering a dialogue with the woman who used to manipulate my emotions like puppet strings. I wasn’t going to give her anything she could throw back at me.

“I have realised that this frail bridge between my mum and me is seemingly permanent, it is likely to also be permanently fractured”

I couldn’t write that I loved her. Still, that didn’t stop me from ringing the hospital multiple times a day in order to speak to a doctor, or sending her photos of my time at university so she could see what I now looked like. In the end, I had to settle for a more nuanced sentiment: “I never forgot you,” and “I still care about you.”

The response I received was gushing. It was plastered with “I love yous” and bore signs of her declining health in the frail handwriting. In typical fashion, the guilt over being so impersonal sank in my stomach like a lead balloon, but then I remembered this was exactly why I hadn’t wanted to be more sentimental in the first place.

It was upon receiving a reply and tentatively reconstructing a frail, creaking wooden bridge between us that my thoughts began to centre on my own health. As a precocious child born in 1999, I would loudly declare that I would choose to live until I was 101 just so I could live in three centuries. Now, I might be lucky if I manage even half of that.

As I’m writing this, the film “sequel” is not yet over. I have realised that this frail bridge between my mum and me is seemingly permanent, it is likely to also be permanently fractured. The communications between us still remain quite irregular, and I don’t have any preconceived ideas of what I want that relationship to be. I just know that blood is not thicker than water, and that relationship is not exactly a mother-daughter one anymore: it’s something other.

I am currently in the process of being tested for the genetic mutation that triggers Huntington’s disease. This uncertainty over my future, over my closure, I am fortunate enough to be discussing now as a hypothetical. Of course, in time, that will no longer be the case. I can hope that this condition is not something I will have to face, but there is currently a 50% chance that I will, and so I will cross that (hopefully much sturdier) bridge when I come to it.

For more information about Huntington’s disease, the Huntington’s Disease Association is an incredible charity that provides support for families dealing with the disease.

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026