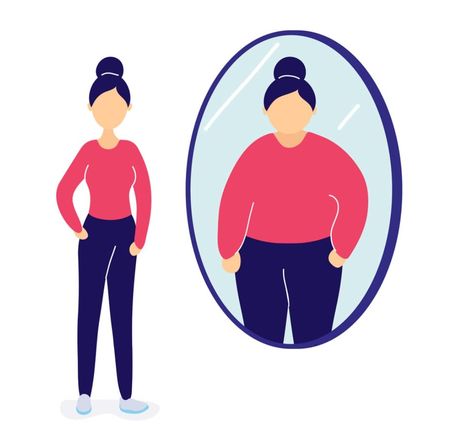

Acknowledging Body Dysmorphia

A recent graduate reflects on her journey with body dysmorphia and the importance of taking it seriously

Content Note: This article contains discussion of eating disorders.

It started as not wanting to go to a party. The dress I had bought refused to look the way I envisioned a week later and I decided that only once I lost weight could I attend the next one. It was a seemingly innocuous habit- every time I had a crisis in body image I would tell myself that my friends would only want to see me once I felt better about my appearance. I would dread the occasions when I could not avoid them; shrouding my body in anything I could find. My concept of body dysmorphia at the time was intangible and vague at best.

GCSEs and A-Levels both came and went, but little had improved. My perception of events was increasingly determined by how I felt about my body. I began to develop an unhealthy relationship with exercise. I wondered if I had to “fix” my body in order to have a place in the professional world. Achievements began to hold less worth as my identity became entangled with a quietly deteriorating body image. There were still no alarms, no sirens – being “body dysmorphic” was a problem so associated with the coming-of-age experience that I was convinced crying wolf would only make it worse.

"My metabolism became so unstable that I was gaining weight on pieces of fruit."

Come the beginning of Cambridge, an unhealthy relationship with exercise quickly spiralled into spending hours exercising alone in my room. My body became something I began to feel constantly apologetic for; run-ins with even remote acquaintances were laced with the fear of them noticing my weight fluctuating. The then widely used definition of having body dysmorphia as ‘spending a lot of time worrying about your appearance’ further exacerbated my difficulty in acknowledging that feeling this way fell under the umbrella of a larger problem. One year snowballed into two, and I started performing a balancing act between going to the gym for long hours and alternating between restricting and overindulging on fear foods. In third year I discovered juice cleanses, starvation diets and extreme exercise challenges. My metabolism became so unstable that I was gaining weight on pieces of fruit.

The single-minded momentum of this issue had gained traction too fast for the sirens to register. I decided that once I had achieved my goal I could retrospectively acknowledge what I knew even back then: this was an eating disorder. I was terrified of speaking to anyone about it, for fear of the consequences of accepting how far I had come from ‘spending a lot of time worrying about my appearance’. Acknowledging my spiralling body image in the fast-paced Cambridge bubble became an impossibility.

In my fourth and final year, I became meticulous in my knowledge of macronutrient ratios and balancing exercise intensity and caloric density. I had to weigh proteins, google calorie counts; the difference between 120 and 122 grams started to feel immense. Deviating even slightly from my prescribed plan would result in a teeter, then a tumble, off what felt like a sharp edge around my fear foods. I was panic-stricken at the thought of anyone discovering how incongruent the whole situation made me feel, and terrified that they already had. It was only after finishing my last term at Cambridge that I started a journey of recovery.

"Now I no longer need to “fix” my body, because it is already whole."

Since finishing my final term I have come a long way in rebuilding a healthy relationship with exercise and nutrition. I have acknowledged and been kind to myself on the tough days. I have let myself speak to loved ones about it. Above all, the experience taught me the importance of letting yourself take the symptoms seriously. Body dysmorphia is not just a mild inconvenience, a runny nose in lieu of the full-blown flu. It is not a coming-of-age experience, to be ignored until it cannot any longer. Now, I catch myself in the small habits I have learnt to recognise. Now I no longer need to “fix” my body, because it is already whole.

If you are affected by any of the issues raised in this article, the following services provide support and resources:

- The University Counselling Service: currently offers remote consultations.

- Samaritans: a 24-hour mental health helpline

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 News / Law don launches divestment petition12 March 2026

News / Law don launches divestment petition12 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026